Scaling Frontend Architecture: A Practical Guide

TLDR:

Guides frontend teams from ad-hoc structures to scalable architectures by comparing layered, component-based, micro-frontend, and domain-driven patterns and their trade-offs.

Frontend scalability is the blueprint that keeps a large-scale frontend fast, maintainable, and resilient as teams and features grow. Without a clear structure, enterprise frontend systems quickly degrade into fragile spaghetti code, hurting performance at scale and slowing every release. A modern methodology like Feature-Sliced Design, developed by the community at feature-sliced.design, offers opinionated yet flexible building blocks for structuring complex UI, business logic, and state in a way that scales with your product.

Why a Deliberate Approach to Frontend Scalability Is Non-Negotiable in 2025

Modern Single Page Applications and rich client interfaces now own responsibilities that used to live exclusively on the server: routing, state management, caching, optimistic updates, offline behavior, accessibility, and complex interaction flows. As applications evolve from simple views into full-blown products, frontend scalability becomes a multidimensional problem rather than a question of “Can the React app render?”.

At a high level, scalable frontend architecture means that adding:

- a new feature does not require refactoring half the codebase,

- a new developer does not require months of tribal-knowledge transfer,

- a new business requirement does not trigger a risky rewrite, and

- a spike in traffic does not break performance guarantees.

Practically, you can think of frontend scalability across four dimensions:

- Code scalability – The codebase supports more features, modules, and edge cases without collapsing under its own complexity. This is largely a function of cohesion, coupling, and the clarity of boundaries.

- Team scalability – Multiple squads can work on the same large-scale frontend with minimal merge conflicts and without stepping on each other’s abstractions.

- Performance at scale – Core Web Vitals, perceived latency, and responsiveness remain stable as bundles, routes, and widgets multiply.

- Operational scalability – Builds, tests, and deployments stay predictable, even in a monorepo with many apps and shared packages.

When these dimensions are not addressed deliberately, familiar symptoms appear:

- “God components” of thousands of lines implementing multiple features.

- A single global store where all state is dumped “because it’s easier”.

- Cross-cutting imports like

../../componentssprinkled everywhere. - Feature flags woven directly into UI components instead of encapsulated behavior.

- Onboarding that takes months because folder structures reflect history, not intent.

- “We can’t touch that file, it breaks everything” zones in the codebase.

A key principle in software engineering is that change is the constant, not the exception. Architectures optimized only for the current shape of the product lock you into today’s decisions. Architectures optimized for change enforce modularity, stable interfaces, and clear dependency flows.

This is exactly where deliberate frontend architecture — and especially Feature-Sliced Design (FSD) — shines. By organizing the code around business capabilities and features instead of framework quirks, you create a structure that evolves with the product rather than fighting against it.

Common Approaches to Building a Large-Scale Frontend Architecture

Before diving into FSD, it helps to understand the most common frontend architecture patterns used in large projects today. Each pattern scales in some dimensions but struggles in others. There is no universal silver bullet; instead, you want to understand the trade-offs and then select the combination that fits your context.

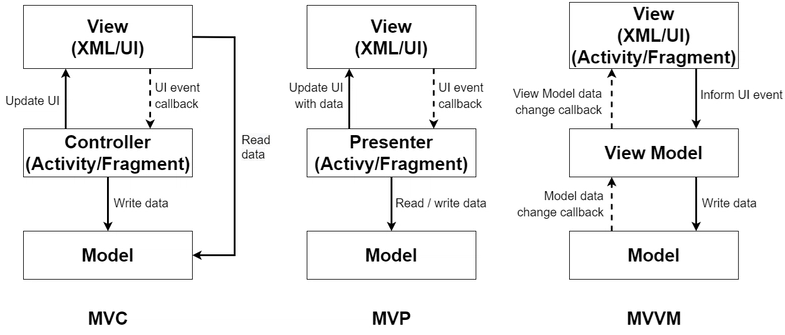

Layered Architectures (MVC, MVP, MVVM) for Web UIs

Layered architectures such as MVC, MVP, and MVVM organize code by technical role:

- Model – Data structures and business rules.

- View – UI rendering.

- Controller/Presenter/ViewModel – Glue code that coordinates user input, state changes, and navigation.

A typical directory may look like:

src/

models/

views/

controllers/

This improves separation of concerns compared to ad-hoc structures and can work well for small to medium apps or server-rendered UIs. It is conceptually simple and matches how many frameworks introduced themselves historically.

However, as the app grows, you often see:

- Overgrown controllers/view-models containing logic for multiple features.

- Cross-layer leakage, e.g. views querying APIs directly “just this once”.

- Difficulty mapping business capabilities to code because logic is split horizontally by layer.

Coupling tends to grow around controllers and shared utility modules, while cohesion within each “slice of behavior” decreases. For true frontend scalability, you usually need a more vertical, feature-centric decomposition.

Component-Driven Frontend and Atomic Design Systems

With React, Vue, Svelte, and modern Angular, the component became the unit of reuse and composition. Atomic Design formalized a vocabulary:

- Atoms – Smallest reusable pieces (button, input, icon).

- Molecules – Combinations of atoms (search field with button).

- Organisms – Complex sections (header, product card).

- Templates/Pages – Layouts and concrete page instances.

A component-driven approach gives you:

- Consistent UI through shared design tokens and theming.

- Highly reusable building blocks for product teams.

- A clear path to building a design system or UI kit.

For frontend scalability, this architecture is almost mandatory. It reinforces visual consistency, makes refactors cheaper, and helps teams speak a common UI language.

But it answers only part of the question. Atomic Design is mostly about what the UI looks like, not how the application behaves. Questions like:

- Where should API calls live?

- How do we structure complex workflows?

- How do we isolate business logic?

remain open. As your large-scale frontend evolves, component trees that contain business rules, validation, and domain logic become hard to maintain. Component-based architecture is necessary, but not sufficient, for scaling behavior and data flows.

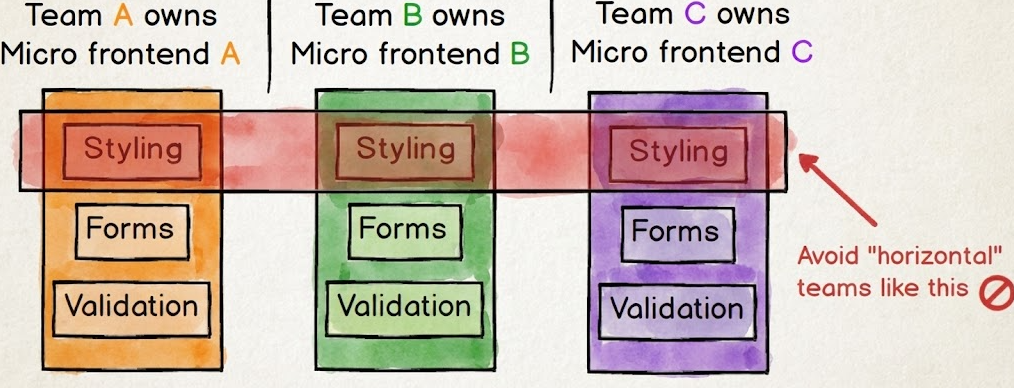

Micro-Frontends and Federated Frontend Platforms

Micro-frontends apply microservice thinking to the browser. Instead of one monolithic SPA, you have multiple independently deployed applications that together form a unified experience. For example:

- A “catalog” micro-frontend for browsing products.

- A “checkout” micro-frontend for cart and payments.

- A “profile” micro-frontend for user account management.

Integration can happen at:

- Route level – Different paths render different micro-apps.

- Component level – Composition via iframes, Web Components, or module federation.

This pattern shines in enterprise frontend environments where dozens of teams must ship independently and own their domains end-to-end. It scales team autonomy and deployment velocity.

However, you pay in complexity:

- Shared dependencies must be carefully versioned and loaded.

- Cross-micro-frontend state (e.g. the cart) is harder to keep consistent.

- UX consistency requires a strong design system and governance.

- Performance at scale can suffer if each micro-frontend loads its own heavy bundle.

Micro-frontends tell you how to split the application into deployable units, but they do not prescribe how to structure code inside each unit. Even with micro-frontends, you still need an internal architecture pattern such as FSD.

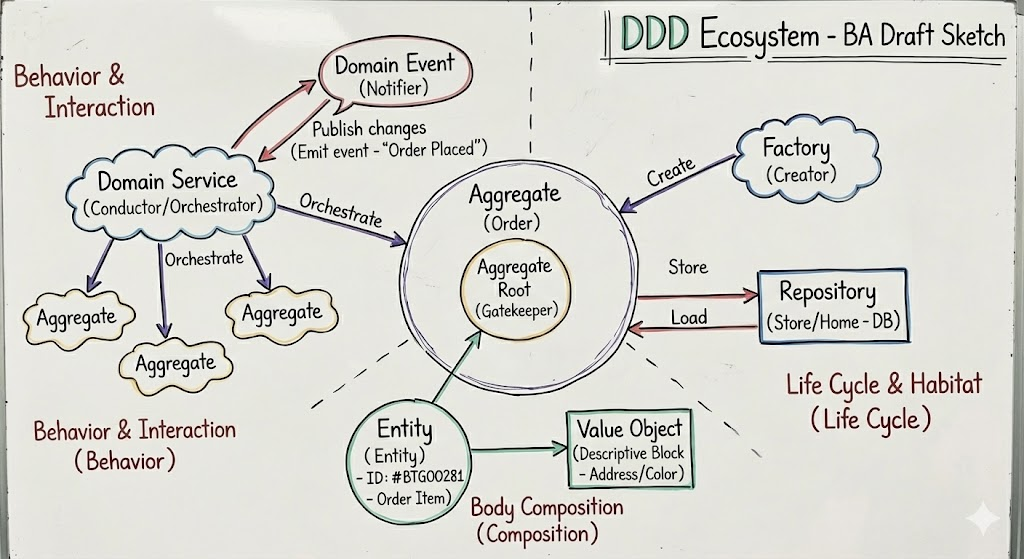

Domain-Driven and Feature-Based Frontend Organization

Borrowing from Domain-Driven Design (DDD), many teams organize frontend code by business domains and features. Instead of grouping by technical type, they group by functional behavior:

src/

domains/

product/

cart/

user/

shared/

Within each domain, you might have subfolders for components, hooks, and services. This raises cohesion: everything about “cart” or “user” is colocated. It also maps nicely to how business stakeholders talk about the system.

On a large-scale frontend, this unlocks:

- Clear bounded contexts aligned with product areas.

- Easier domain modeling and ubiquitous language.

- Natural ownership for teams (each domain owned by a squad).

The downside is that a “domain” is still a wide concept. You can end up with:

- Huge domain folders where unrelated behaviors accumulate.

- Tight coupling between domains through deep imports.

- Inconsistent layering within each domain (some features go through services, others bypass them).

Feature-based organization is a powerful step toward scalable architecture, but you need more explicit rules about layers, dependencies, and public APIs to keep the structure healthy as the app evolves.

Monorepos and Modular Package Architectures

Monorepos (with tools like Nx, Turborepo, or pnpm workspaces) solve the problem of scaling code sharing across multiple apps and libraries. You might have:

apps/– customer-facing SPAs, admin panels, internal tools.libs/– shared UI, utilities, domain models, API clients.

Monorepos enable:

- Centralized tooling and CI/CD.

- Consistent linting and formatting across the ecosystem.

- Incremental builds and testing for faster feedback.

- Reuse of domain logic and UI across multiple frontends.

However, monorepos are repository-level architecture, not application-level architecture. Without clear module boundaries inside each app, a monorepo can just as easily produce a distributed ball of mud.

You still need a methodology — like Feature-Sliced Design — to decide:

- What goes into

appvsfeaturesvsentities. - How libraries should expose public APIs.

- How to avoid cross-feature coupling via shared “god” utilities.

Feature-Sliced Design (FSD): A Practical Blueprint for Frontend Scalability

Feature-Sliced Design (FSD) is a frontend architecture methodology designed specifically for frontend scalability. It combines lessons from layered architectures, DDD, component-driven design, and large-scale product development into a coherent, enforceable structure.

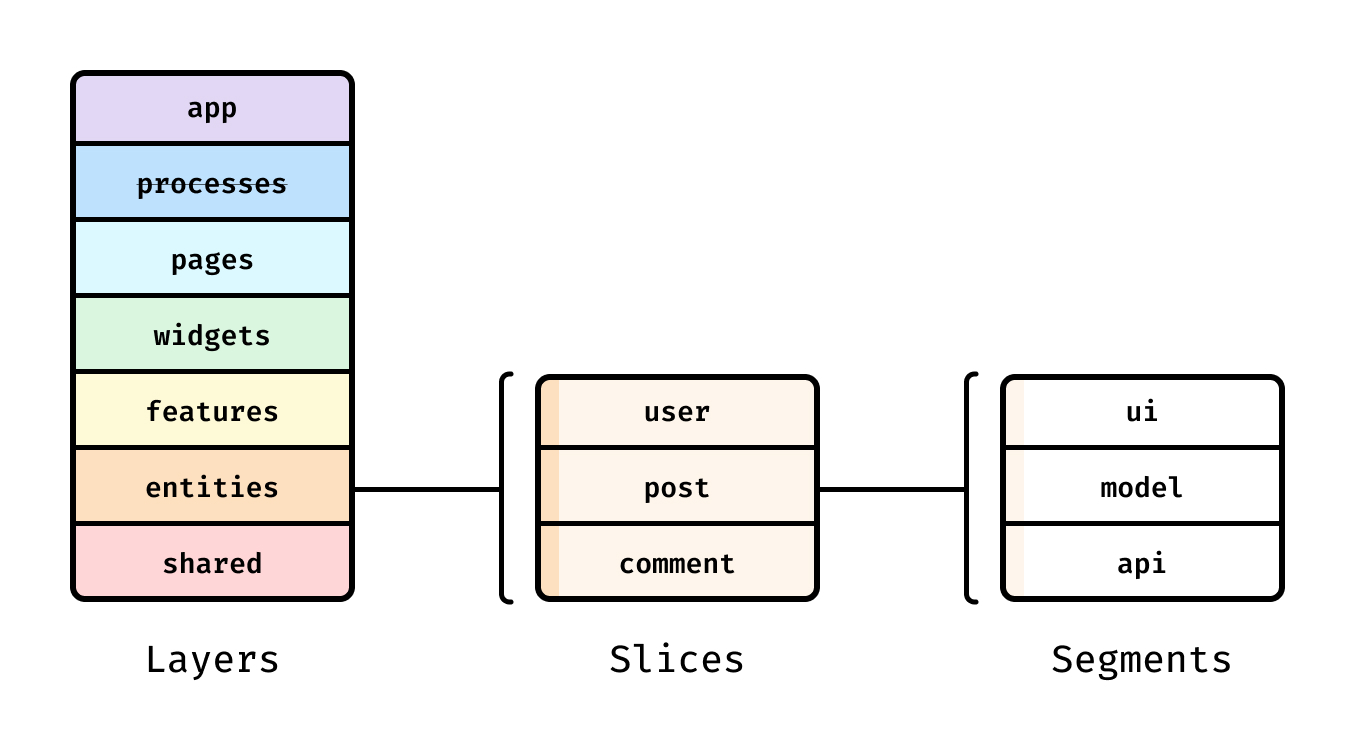

Instead of structuring by framework constructs (components, services) or broad domains only, FSD structures code by layers and slices:

- Layers define how close code is to the end user (from app shell down to shared utilities).

- Slices define what business capability or entity the code represents (from “update-profile” to “cart” or “user”).

This yields a frontend that scales along three axes:

- features (you can keep adding slices),

- teams (you can assign slices to owners), and

- technology (you can replace internals behind stable public APIs).

Core Principles of Feature-Sliced Design

Several key principles drive FSD in real-world projects:

- Decompose by feature and entity, not by technical type. Code for a given user scenario (“like post”, “add to cart”) or business entity (“user”, “product”) lives together instead of being spread across

components/,services/, andstore/. - Strong cohesion within slices, low coupling between slices. A slice encapsulates UI, state, and logic for its concern. Other slices interact only through its public API.

- Layered dependency rules. Upper layers can depend on lower layers, but lower layers must not import from higher ones. This keeps data flow predictable and prevents dependency cycles.

- Explicit public APIs. Each slice has an

indexthat defines what is exported. Everything else is considered internal implementation. - Isolation and testability. Because behavior is encapsulated per slice, you can test features in isolation and refactor internals without breaking unrelated parts.

In practice, these principles drastically reduce accidental coupling and make it easier to reason about complex behavior in a large-scale frontend.

Layers and Slices in FSD

A typical FSD project uses the following layers (from outermost to innermost):

- app – Application initialization and configuration (routing, global providers, shell).

- processes (optional) – Long-running business processes that span multiple pages (e.g., onboarding funnels).

- pages – Route-level pages composed from widgets and features.

- widgets – Composite UI blocks that combine features and entities (e.g., feed, profile header).

- features – User interactions and business scenarios (e.g.,

auth-by-email,add-to-cart). - entities – Core business entities (e.g.,

user,product,order) with their state and UI primitives. - shared – Purely reusable, business-agnostic code (UI kit, helpers, config).

Visually, you can imagine a vertical stack:

app → processes → pages → widgets → features → entities → shared

Dependencies are only allowed downwards in this stack. For example, a feature may depend on entities and shared but never on pages or widgets.

A realistic directory structure might look like:

src/

app/

providers/

routing/

index.ts

pages/

profile/

ui/

model/

index.ts

catalog/

ui/

model/

index.ts

widgets/

profile-header/

ui/

model/

index.ts

product-grid/

ui/

model/

index.ts

features/

update-profile/

ui/

model/

index.ts

add-to-cart/

ui/

model/

index.ts

entities/

user/

ui/

model/

index.ts

product/

ui/

model/

index.ts

shared/

ui/

lib/

api/

config/

Each slice (profile, update-profile, user, etc.) has its own folder with UI and model logic colocated. This is where FSD’s vertical slicing aligns particularly well with feature-based thinking.

Public API and Dependency Rules

The public API of a slice is usually defined in its index file. Only this file may be imported from the outside. Internals are hidden behind that facade.

For example, in a feature slice:

// features/update-profile/index.ts

export { UpdateProfileForm } from "./ui/UpdateProfileForm";

export { useUpdateProfile } from "./model/useUpdateProfile";

In a page slice:

// pages/profile/index.ts

export { ProfilePage } from "./ui/ProfilePage";

And then used elsewhere:

// app/routing/config.ts

import { ProfilePage } from "pages/profile";

// widgets/profile-header/ui/ProfileHeader.tsx

import { UpdateProfileForm } from "features/update-profile";

import { UserAvatar } from "entities/user";

Notice what is not allowed:

- Importing

./ui/UpdateProfileFormdirectly from outside the feature. - Importing

modelinternals of an entity from a random feature. - Cross-layer imports that go “up” (e.g., an entity importing from a feature).

These rules keep dependencies predictable and ensure that when you change internals in features/update-profile/model, you only need to verify slices that depend on the public API of features/update-profile.

Linters and custom tooling can enforce these rules automatically (for example, by checking import paths against layer rules and slice boundaries).

How FSD Supports Frontend Scalability in Practice

FSD’s structure unlocks concrete benefits for large-scale frontend development.

1. Code scalability through explicit boundaries

Each new feature usually maps to:

- a new

features/<feature-name>slice, - optional small additions to

entitiesorwidgets, and - minor wiring in

pagesorapp.

You rarely need to modify many unrelated parts of the system. This keeps your change surface area small, which reduces bugs and makes refactoring safer.

2. Team scalability and ownership

Slices can be mapped to teams or product areas:

- The “Profile” squad owns

pages/profile,widgets/profile-*,features/update-profile, andentities/user. - The “Catalog” squad owns relevant pages, widgets, and

entities/product.

This aligns repository structure with organizational structure, an important principle for large teams. Developers can work largely within their slices without constantly coordinating with every other team.

3. State management that scales with data complexity

In FSD, you typically colocate state with the entity or feature that owns it:

entities/

user/

model/

store.ts

selectors.ts

ui/

UserAvatar.tsx

UserMenu.tsx

features/

auth-by-credentials/

model/

useLogin.ts

ui/

LoginForm.tsx

The user entity can expose a stable state API:

// entities/user/index.ts

export { useCurrentUser, userModel } from "./model";

export { UserAvatar } from "./ui/UserAvatar";

The auth-by-credentials feature depends only on this public API:

// features/auth-by-credentials/model/useLogin.ts

import { userModel } from "entities/user";

export const useLogin = () => {

// invoke userModel actions, handle side effects

};

This pattern works whether you are using Redux Toolkit, Zustand, Vuex, Pinia, or another store — the methodology is agnostic. What matters is that:

- domain state lives in entities,

- interaction logic lives in features, and

- components consume state through stable public APIs.

This drastically improves data-flow clarity in complex, large-scale frontends.

4. Performance at scale aligned with architecture

Because FSD structures code by layers and pages, it pairs naturally with performance techniques:

- Route-based code splitting maps directly to

pages. - Feature-level lazy loading applies to heavy

features(e.g., rich editors, analytics dashboards). - Entity-level caching ensures shared data like

userorproductis fetched once and reused.

By aligning code organization with runtime behavior, FSD makes it easier to maintain performance budgets as features grow.

5. Compatibility with other patterns

FSD does not forbid micro-frontends, monorepos, or design systems. Instead:

- A micro-frontend can internally follow FSD.

- A monorepo can host multiple FSD-based apps and shared slices.

- A design system can live inside

shared/uiand be reused across slices.

This makes FSD a pragmatic, composable blueprint for frontend scalability rather than an all-or-nothing framework.

A Step-by-Step Guide to Scaling an Existing Frontend Codebase

Knowing the concepts is useful, but architects and tech leads also need a practical migration path. The good news: you do not need a big-bang rewrite. You can apply FSD and scalability principles incrementally, using a “strangler fig” approach.

Step 1: Define Your Scalability Goals and Constraints

Before restructuring, clarify why you are doing it. For example:

- Reduce the average time to implement a new feature from weeks to days.

- Improve Core Web Vitals on key pages without sacrificing functionality.

- Make onboarding a new engineer possible within a couple of weeks.

- Reduce merge conflicts between teams working on the same large-scale frontend.

Capture a small set of metrics:

- Number of modules touched per typical feature.

- Bundle size per critical route.

- Build and test times in CI.

- Incidents caused by front-end changes.

These become your baseline and help you evaluate whether architecture changes are delivering real value.

Step 2: Map the Current Architecture and Pain Points

Next, build a lightweight map of your current system:

- What are the main domains (e.g., catalog, search, cart, profile)?

- Where are the god components and god modules?

- How is state structured (one massive store, ad-hoc hooks, mixed patterns)?

- Where do cross-cutting concerns (analytics, feature flags, authorization) live?

You might discover patterns like:

components/andcontainers/folders with no clear meaning anymore.- Custom hooks importing everything from everywhere.

- Deep relative imports such as

../../../store/userSlice.

Document these pain points. They will guide which parts to refactor first and which boundaries to introduce.

Step 3: Introduce Modular Boundaries Around Features and Entities

Start by carving out clear feature and entity slices in just one area — usually a high-impact, actively developed flow such as onboarding or checkout.

For example, you might transform:

src/

components/

ProfileForm.tsx

Avatar.tsx

store/

user.ts

pages/

ProfilePage.tsx

into:

src/

pages/

profile/

ui/

ProfilePage.tsx

index.ts

features/

update-profile/

ui/

UpdateProfileForm.tsx

model/

useUpdateProfile.ts

index.ts

entities/

user/

ui/

UserAvatar.tsx

model/

store.ts

selectors.ts

index.ts

Then:

- Update imports in the rest of the app to go through

pages/profile,features/update-profile, andentities/user. - Add simple lint rules or code review checks that forbid new imports from deprecated locations.

By repeating this process feature by feature, you gradually move from a “horizontal” architecture (components, store, services) to a feature-sliced one without freezing development.

Step 4: Refine State Management for Data Complexity at Scale

Once you have clear slices, refine state management so it aligns with your architecture:

- Entity state – Core domain data (current user, products, orders) lives in

entities. Libraries like Redux Toolkit or Zustand can be wrapped behind entity APIs. - Feature state – Temporary or scenario-specific state (form step, filter selection) lives in

features. - Page/widget state – Purely presentational or orchestration state (which tab is open) lives close to the component.

Guidelines that help with scalability:

- Avoid “one global store for everything”. Split state by entity and feature.

- Expose only well-defined selectors and actions via the entity’s public API.

- Use libraries like React Query or SWR to handle server cache, and wrap them in

entitiesorshared/apiso usage stays consistent.

For example:

entities/

product/

model/

useProductList.ts // wraps data fetching and caching

ui/

ProductCard.tsx

features/

filter-products/

model/

useProductFilters.ts

ui/

ProductsFilterPanel.tsx

pages/

catalog/

ui/

CatalogPage.tsx

The CatalogPage composes ProductCard and ProductsFilterPanel without needing to know exactly how products are fetched or how filters are stored internally. This decoupling is crucial as data complexity grows.

Step 5: Align Performance Optimization with Architectural Boundaries

Performance at scale is not just about micro-optimizing components; it is about loading the right code at the right time. FSD provides natural boundaries for performance strategies:

- Pages are ideal units for route-based code splitting.

- Heavy features (e.g., charts, WYSIWYG editors) can be lazy-loaded as separate chunks.

- Entities can centralize data fetching and caching, avoiding duplicate network calls.

Practical tactics:

- Lazy-load non-critical widgets and features on scroll or interaction.

- Keep

sharedsmall and focused; massive shared modules become bottlenecks. - Monitor bundle sizes per page and track them in CI, treating them as part of your scalability budget.

- Use server-side rendering or static generation where appropriate, but keep the FSD structure on the client for maintainability.

Because architecture and performance boundaries align, you can adjust what loads where without rewriting your entire app.

Step 6: Scale Team Processes Around the Architecture

Architecture alone will not guarantee scalability; processes must support it.

Consider introducing:

- Code ownership per slice – Each feature and entity has named maintainers.

- Pull request boundaries – PRs should typically touch a small set of related slices rather than many unrelated modules.

- Architecture Decision Records (ADRs) – Capture decisions about layer rules, naming, and conventions.

- Automation – Lint rules that enforce import rules, CI jobs that check bundle sizes, generators that scaffold new slices with a consistent layout.

Leading architects suggest treating the architecture as a contract between teams. FSD makes that contract explicit through layers and public APIs; your processes reinforce it.

Over time, the combination of a structured design and disciplined processes yields a frontend that can evolve quickly without sacrificing stability.

Comparative Analysis: Choosing the Right Scalable Frontend Architecture

With several patterns available, how do you decide which to emphasize for your project? The table below summarizes the main strengths of each architectural approach in the context of frontend scalability.

| Architectural pattern | Core principle | Best for |

|---|---|---|

| Layered (MVC/MVP/MVVM) | Separation of concerns by technical role (data, UI, control logic). | Small to medium apps with modest complexity and simple team structures. |

| Component/Atomic Design | Decomposition of UI into reusable, self-contained visual components. | Any modern SPA that needs a consistent design system and UI library. |

| Micro-frontends | Split the UI into independently deployable, loosely coupled applications. | Enterprises needing strong team autonomy and independent deployments. |

| Domain/Feature-based design | Group code by domain concepts and user-facing features. | Products with rich business logic and multiple bounded contexts. |

| Feature-Sliced Design (FSD) | Layered, feature- and entity-centric slices with explicit public APIs. | Medium to large-scale frontends needing long-term maintainability. |

Some practical guidance:

- If your main challenge is UI consistency and design reuse, invest heavily in component-driven and Atomic Design patterns. They will remain foundational for any approach.

- If your main challenge is organizational scaling across dozens of teams and apps, micro-frontends plus a monorepo may be justified, but be aware of the integration and performance costs.

- If your main challenge is business complexity and maintainability, domain/feature-based patterns and FSD are usually the most impactful.

- FSD, in particular, offers a balanced, incremental path: you can adopt it inside a single app, inside a micro-frontend, or as a structure for multiple apps in a monorepo, without requiring radical changes to your tooling stack.

Rather than choosing one pattern exclusively, many successful teams combine them:

- Component-driven UI + design system.

- Monorepo for multi-app ecosystem.

- FSD as the internal architecture for each app.

- Optional micro-frontends at the routing layer for extreme team autonomy.

Conclusion: Investing in a Structured Future

Scaling frontend architecture is ultimately about optimizing for change. As products grow, teams expand, and requirements shift, an ad-hoc structure becomes a liability. By deliberately organizing code around features, entities, and layers, you gain a frontend that can evolve without constant rewrites or regressions.

Feature-Sliced Design offers a robust methodology for achieving this kind of frontend scalability. It brings together component-driven development, domain thinking, and clear dependency rules into a single, practical blueprint. As demonstrated by projects using FSD in production, this approach improves maintainability, performance at scale, and developer experience across large teams.

Ready to build scalable and maintainable frontend projects?

Dive into the official Feature-Sliced Design Documentation to get started.

Have questions or want to share your experience?

Join our active developer community on Website!

Disclaimer: The architectural patterns discussed in this article are based on the Feature-Sliced Design methodology. For detailed implementation guides and the latest updates, please refer to the official documentation.