Monorepo Architecture: The Ultimate Guide for 2025

TLDR:

A modern frontend monorepo isn’t just “multiple apps in one repo”—it’s a dependency graph with enforced boundaries, shared tooling, and predictable delivery. This guide covers when monorepos beat polyrepos, how to choose between Turborepo and Nx, how to set up pnpm workspaces, and how Feature-Sliced Design keeps packages and apps maintainable as teams and codebases grow.

Frontend monorepo teams usually don’t fail because Git can’t handle a big repo—they fail because boundaries, tooling, and ownership aren’t designed for scale. In 2025, modern build systems, workspace package managers, and strong architectural conventions (like Feature-Sliced Design from feature-sliced.design) make a single-repo frontend codebase both fast and maintainable—without “spaghetti sharing” and CI bottlenecks.

Table of contents

- What a frontend monorepo is and why it matters in 2025

- Monorepo vs polyrepo: how to choose without ideology

- The core mechanics: packages, boundaries, and public APIs

- Tooling in 2025: Turborepo, Nx, pnpm workspaces, Lerna

- Step-by-step: create a frontend monorepo with pnpm + Turborepo

- Step-by-step alternative: Nx workspace when you need a “platform”

- Dependency management and versioning that won’t collapse later

- CI/CD for a frontend monorepo: fast pipelines, predictable deploys

- Where Feature-Sliced Design fits: architecture inside apps and packages

- Common frontend monorepo problems and proven fixes

- Migration plan: move to a frontend monorepo without stopping delivery

- Conclusion

What a frontend monorepo is and why it matters in 2025

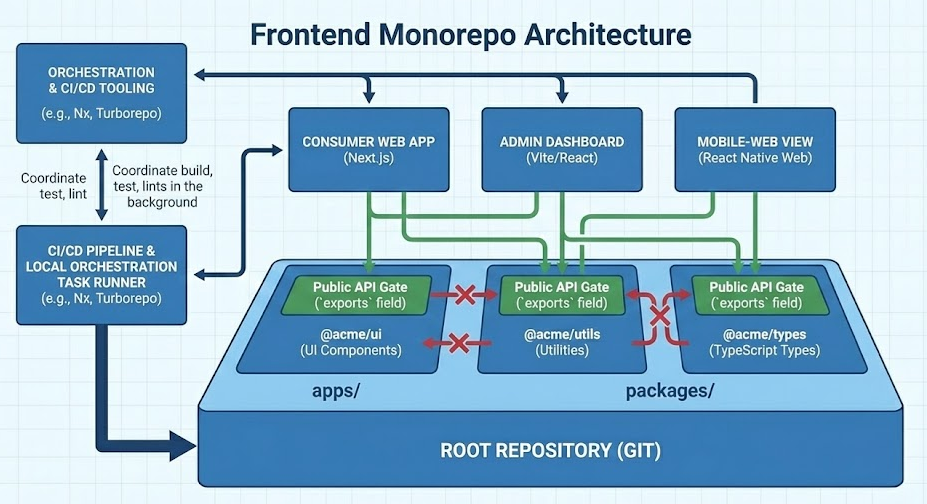

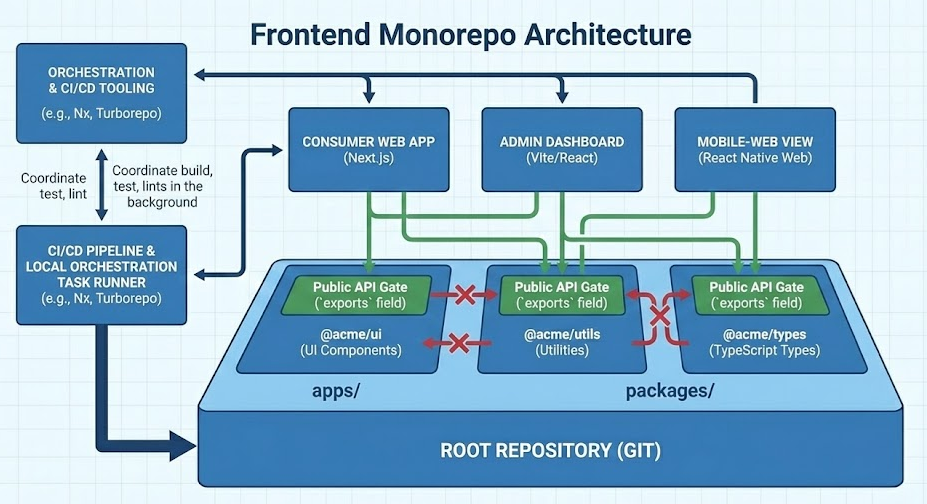

A frontend monorepo is a single Git repository containing multiple frontend projects—often multiple apps (web, admin, mobile web), shared UI libraries (design system, component library), and shared tooling (lint rules, TypeScript configs, build presets). The defining property isn’t “many folders,” it’s one shared history and one coherent dependency graph.

This matters because frontends are increasingly “product platforms,” not isolated SPAs:

- Multiple apps share UI primitives, routing conventions, analytics, feature flags, auth clients, i18n, and domain contracts.

- Teams need atomic refactors (change API + update all consumers in one commit).

- Build time and CI cost explode if every PR rebuilds everything.

A key principle in software engineering is that modularity must be enforced, not hoped for. A monorepo gives you the opportunity to do that well: shared tooling, consistent structure, and explicit APIs—especially when combined with an architectural methodology like Feature-Sliced Design (FSD).

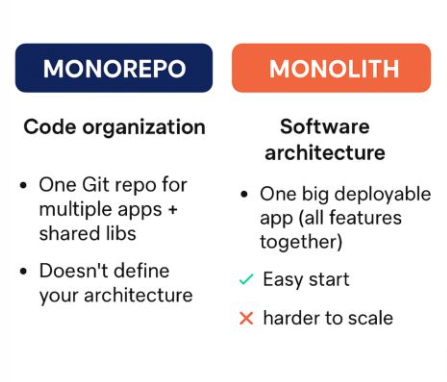

Monorepo ≠ monolith

"Monorepo" is about version control, not architecture. You can have:

- A monorepo containing cleanly isolated packages with stable public APIs (high cohesion, low coupling).

- A monorepo containing a giant blob where everything imports everything (low cohesion, high coupling).

The second is a monorepo-shaped mess. The first is a scalable system.

The mental model: a package graph, not a folder tree

Think in nodes and edges:

- Nodes: apps and libraries (packages).

- Edges: dependencies between them (imports, package.json dependencies).

- Rules: which edges are allowed (module boundaries, public APIs, ownership).

Diagram description (useful for onboarding docs):

- Draw boxes for

apps/web,apps/admin,packages/ui,packages/shared,packages/config. - Draw arrows only from apps to packages, and from feature packages to shared primitives.

- Mark "no arrows allowed" rules (e.g.,

sharedmust not importfeatures).

This simple diagram catches 80% of scalability issues early.

Monorepo vs polyrepo: how to choose without ideology

A robust methodology for architecture starts with the truth: there is no one-size-fits-all repository strategy. “Monorepo vs polyrepo” is a trade-off across coordination, coupling, and delivery speed.

Choose a frontend monorepo when these are true

A frontend monorepo is usually a great fit when:

- You maintain multiple apps that share a UI kit, design tokens, domain models, or API clients.

- You frequently need cross-cutting changes (design refresh, i18n change, auth update).

- You want consistent developer experience: one set of scripts, linting, testing, formatting, and conventions.

- You can commit to boundary enforcement (public APIs, lint rules, ownership).

High-leverage sign: you’re already copy-pasting packages or maintaining “shared” in multiple repos.

Prefer polyrepo when these are true

A polyrepo approach is usually safer when:

- Apps are truly independent products with separate release cycles and little shared code.

- Security/compliance requires strict repository separation and different access control models.

- Teams are fully autonomous and the organization values “loose coupling” over “shared platform.”

The real decision: coordination cost vs integration cost

- Polyrepo reduces “everyone touches everything,” but increases integration cost (version bumps, cross-repo PRs, compatibility matrices).

- Monorepo reduces integration cost (atomic commits) but requires discipline: boundaries, CI strategy, and ownership.

Leading architects suggest making the decision based on change frequency across boundaries. If cross-project changes are common, a monorepo tends to pay back quickly.

Quick decision checklist (pragmatic, not theoretical)

If you answer “yes” to 4+ of these, a frontend monorepo is likely beneficial:

- Do multiple apps share a design system or component library?

- Do you ship shared SDKs (analytics, auth, feature flags)?

- Are coordinated refactors frequent (API change + consumers)?

- Is onboarding slow due to inconsistent setup across repos?

- Is CI cost high because each repo repeats the same work?

- Do you struggle with dependency drift (React versions, ESLint rules)?

- Do you want consistent architectural rules (e.g., FSD layers) across products?

The core mechanics: packages, boundaries, and public APIs

A frontend monorepo scales when you treat it like a modular system:

- Cohesion: each package owns one responsibility.

- Coupling: dependencies flow one way, through explicit contracts.

- Isolation: internal details don't leak across package boundaries.

- Public API: consumers import from stable entry points, not deep paths.

A baseline structure that stays readable

A common and practical baseline for a frontend monorepo:

repo/ apps/ web/ admin/ packages/ ui/ shared/ api-client/ config/ tooling/ scripts/ package.json pnpm-workspace.yaml tsconfig.base.json

Why it works:

apps/are deployable units (Next.js, Vite, Remix, etc.).packages/are reusable building blocks.tooling/holds scripts and CI helpers so they don’t pollute app code.

Enforce public APIs: “no deep imports”

The fastest way to create unmaintainable coupling is allowing imports like:

import Button from "@acme/ui/src/button/Button"import { mapUser } from "@acme/shared/internal/user/mapUser"

Instead, enforce:

import { Button } from "@acme/ui"import { mapUser } from "@acme/shared"

Pattern: a single entry file per package

packages/ui/src/index.ts packages/ui/src/button/Button.tsx packages/ui/src/button/index.ts

Then re-export intentionally in src/index.ts.

In package.json, define exports to prevent accidental deep imports:

{

"name": "@acme/ui",

"version": "0.0.0",

"exports": {

".": "./dist/index.js"

}

}

This is a small move with huge architectural payoff.

Control dependency direction with “module boundaries”

Module boundaries are the monorepo equivalent of “don’t let the wiring become a jungle.”

Practical enforcement options:

- ESLint rules to ban disallowed imports between directories/layers.

- TypeScript project references (when you want explicit compilation boundaries).

- Tooling rules (Nx module boundary enforcement is a common choice).

- Code ownership (

CODEOWNERS) so changes to shared packages have clear reviewers.

Good boundaries feel helpful, not restrictive: they reduce ambiguity and improve discoverability.

Tooling in 2025: Turborepo, Nx, pnpm workspaces, Lerna

Tooling is where many frontend monorepo attempts either become delightful or painful. The key is to separate concerns:

- Workspace package manager: how dependencies are installed and linked locally.

- Task orchestration / build system: how scripts run across packages efficiently.

- Project graph and policy enforcement: how boundaries are modeled and validated.

pnpm workspaces: a strong default for dependency hygiene

pnpm is popular in monorepos because it’s fast, space-efficient, and encourages strict dependency correctness. Its workspace features make local packages first-class citizens.

A typical workspace file:

pnpm-workspace.yaml

packages:

- "apps/*"

- "packages/*"

A powerful monorepo technique is the workspace protocol:

- Use

workspace:*(or a pinned workspace version) for internal deps. - This prevents accidental resolution to an external registry package.

Example:

// apps/web/package.json

{

"dependencies": {

"@acme/ui": "workspace:*",

"@acme/api-client": "workspace:*"

}

}

This aligns with a key architectural principle: local code should resolve locally.

Turborepo: task pipelines + caching with minimal ceremony

Turborepo shines when you already have a good package structure and you want:

- Fast local dev and CI via incremental builds

- Parallel execution across packages

- Simple pipelines (build depends on build of dependencies)

- Optional remote caching for CI acceleration

It’s often chosen when teams want a lightweight orchestrator without adopting a larger platform.

Nx: a full monorepo platform (graph, generators, policies, CI features)

Nx is designed around a rich project graph:

- It can compute “affected” projects (only run tasks that matter for a PR).

- It supports computation caching (local and remote).

- It offers generators, plugin ecosystems, and policy enforcement.

Nx is a strong choice when your monorepo is a product platform with many teams and you want standardized scaffolding and guardrails.

Lerna in 2025: still useful, but understand its role

Lerna remains a known name in JavaScript monorepos, particularly for package publishing workflows and multi-package management. In modern setups, it’s often used alongside other tools (or integrated with Nx-based task running) rather than being the only system.

If your monorepo’s main complexity is publishing multiple packages with consistent versioning, Lerna can still be relevant. If your main complexity is build/test orchestration and large-scale policy enforcement, teams often lean toward Turborepo or Nx.

Tool comparison table (3 columns)

| Tool | Best fit in a frontend monorepo | Watch-outs / trade-offs |

|---|---|---|

| pnpm workspaces | Fast installs, strict deps, clean local linking (workspace:*) | Requires discipline around peer deps and lockfile ownership |

| Turborepo | Simple pipelines, excellent caching, easy CI acceleration | Policy enforcement and scaffolding are mostly “bring your own” |

| Nx | Strong project graph, affected builds, generators, boundary tooling | More concepts to learn; requires upfront workspace modeling |

| Lerna | Multi-package publishing and repo management patterns | Not a substitute for architecture; pair with clear boundaries and a runner |

A practical selection rubric

Pick based on what hurts today:

- If CI is slow and builds are repeated → Turborepo or Nx (with caching).

- If you need affected builds and strong graph-driven workflows → Nx.

- If you mainly need workspace linking and consistent dependency installs → pnpm workspaces alone may be enough.

- If you publish many packages and versioning is the main pain → Lerna (often with modern runners).

Step-by-step: create a frontend monorepo with pnpm + Turborepo

This is a pragmatic “from zero” setup that works well for many teams in 2025. It’s intentionally simple: you can adopt stricter rules later.

1) Initialize the repo and workspace

mkdir acme-frontend cd acme-frontend git init pnpm init -y

Create pnpm-workspace.yaml:

packages:

- "apps/*"

- "packages/*"

Add a root package.json with useful scripts:

{

"name": "acme-frontend",

"private": true,

"packageManager": "pnpm@9",

"scripts": {

"dev": "turbo dev",

"build": "turbo build",

"lint": "turbo lint",

"test": "turbo test",

"typecheck": "turbo typecheck"

}

}

2) Add Turborepo and create a pipeline

pnpm add -D turbo

Create turbo.json:

{

"$schema": "https://turbo.build/schema.json",

"pipeline": {

"build": {

"dependsOn": ["^build"],

"outputs": ["dist/**", ".next/**", "build/**"]

},

"lint": {

"outputs": []

},

"test": {

"dependsOn": ["^build"],

"outputs": []

},

"typecheck": {

"dependsOn": ["^build"],

"outputs": []

},

"dev": {

"cache": false

}

}

}

Why these settings help:

dependsOn: ["^build"]respects the dependency graph.outputsenable caching of build artifacts.devis not cached (correct, because it’s interactive).

3) Create apps and shared packages

Example folder creation:

mkdir -p apps/web apps/admin packages/ui packages/shared packages/config

Create package manifests (minimal example):

// packages/ui/package.json

{

"name": "@acme/ui",

"private": true,

"version": "0.0.0",

"main": "dist/index.js",

"types": "dist/index.d.ts",

"scripts": {

"build": "tsc -p tsconfig.build.json",

"lint": "eslint .",

"typecheck": "tsc -p tsconfig.json --noEmit",

"test": "vitest run"

}

}

In apps, depend on internal packages using workspace:*:

// apps/web/package.json

{

"name": "@acme/web",

"private": true,

"version": "0.0.0",

"dependencies": {

"@acme/ui": "workspace:*",

"@acme/shared": "workspace:*"

},

"scripts": {

"dev": "vite",

"build": "vite build",

"lint": "eslint .",

"typecheck": "tsc -p tsconfig.json --noEmit",

"test": "vitest run"

}

}

4) Centralize TypeScript and ESLint config (reduce drift)

Create a shared TS base config at root:

// tsconfig.base.json

{

"compilerOptions": {

"strict": true,

"noEmit": true,

"moduleResolution": "Bundler",

"jsx": "react-jsx",

"baseUrl": ".",

"paths": {

"@acme/ui": ["packages/ui/src/index.ts"],

"@acme/shared": ["packages/shared/src/index.ts"]

}

}

}

Each project extends it:

// apps/web/tsconfig.json

{

"extends": "../../tsconfig.base.json",

"include": ["src"]

}

Centralizing config improves consistency, reduces onboarding time, and lowers long-term maintenance cost.

5) Add boundary hygiene early (cheap now, expensive later)

A “simple but effective” rule set:

- Each package has an explicit

src/index.ts. - No deep imports across packages.

- Shared packages shouldn’t import app code (ever).

In ESLint, you can implement bans via import rules or custom constraints. The details vary, but the goal is stable: imports reflect architecture.

6) Run everything

pnpm install pnpm build pnpm lint pnpm test

At this stage, you have a working frontend monorepo with:

- Workspaces for local linking

- A task runner that respects package dependencies

- A clear place to add architecture (next section: FSD)

Step-by-step alternative: Nx workspace when you need a platform

If your organization wants strong defaults, generators, and graph-driven workflows, Nx can provide a structured foundation.

1) Create an Nx workspace

Typical flow (exact commands vary by presets):

npx create-nx-workspace@latest acme-frontend cd acme-frontend

Then generate apps and libraries with Nx generators (React, Next.js, Vite, etc.).

2) Model projects and use “affected” workflows

Nx’s key productivity trick is running tasks only for projects impacted by a change:

- Build only what’s affected

- Test only what’s affected

- Lint only what’s affected

Conceptually:

nx affected -t build nx affected -t test nx affected -t lint

This makes CI pipelines faster and more predictable for large monorepos.

3) Enforce boundaries as policy, not convention

Many large teams appreciate that Nx can encode constraints like:

- “Features can import entities and shared, but not other features.”

- “Apps can import packages, but packages can’t import apps.”

- “Only public APIs are importable.”

Even if you don’t use Nx, this mindset is essential: architecture is an executable specification.

Dependency management and versioning that won’t collapse later

A frontend monorepo feels great until dependencies become “shared chaos.” The solution is to treat dependency management as a first-class design concern.

1) Decide your versioning strategy early

Common strategies:

- Single version policy: one version for the whole repo (simple for internal packages, great for apps).

- Independent versioning: each package versioned separately (useful for published libraries).

For many product monorepos (apps + internal libs), the simplest and most stable approach is:

- Keep internal packages private

- Use

workspace:*links - Version apps by release pipelines, not by internal package versions

If you publish packages externally, consider independent versioning plus release automation.

2) Avoid transitive dependency leaks

Strict workspaces help, but you still need discipline:

- Each package lists its direct dependencies explicitly.

- Shared “god packages” are kept small and composable.

- Peer dependencies (React, React DOM) are handled consistently across the repo.

A strong rule of thumb:

- Apps own framework dependencies (React, router, etc.).

- Shared packages accept those as peer deps or minimal runtime deps.

This reduces “two Reacts in one bundle” class of problems.

3) Establish a “dependency review” policy for shared packages

Because shared packages are high blast-radius:

- Add

CODEOWNERSentries forpackages/ui,packages/shared. - Require at least one platform reviewer for dependency additions.

- Prefer small, well-scoped libraries over large, multi-purpose ones.

This increases trust and keeps the monorepo healthy.

CI/CD for a frontend monorepo: fast pipelines, predictable deploys

CI/CD is where monorepos either become a superpower or a money pit. The goal is simple:

- Don’t do work you don’t need

- Cache the work you must do

- Deploy only what changed

1) Use “affected” thinking even without Nx

Even with Turborepo, you can structure pipelines to run relevant tasks based on the dependency graph and caching.

A healthy CI pipeline for a frontend monorepo often looks like:

- Install dependencies (workspace-aware)

- Lint changed areas (or all, if fast)

- Typecheck (graph-aware if possible)

- Test (unit + integration)

- Build only affected deployables

- Deploy only affected apps

2) Remote caching is a force multiplier

Remote caching makes CI runs faster by reusing build artifacts across machines. In practice, this improves feedback loops and reduces compute cost—especially when many PRs touch shared libraries.

For Turborepo, remote caching is commonly configured via environment variables (provider-specific). For GitHub Actions, a typical pattern is:

# .github/workflows/ci.yml (illustrative)

name: CI

on: [pull_request]

jobs:

build:

runs-on: ubuntu-latest

steps:

- uses: actions/checkout@v4

- uses: pnpm/action-setup@v4

with:

version: 9

- run: pnpm install --frozen-lockfile

- run: pnpm lint

- run: pnpm test

- run: pnpm build

env:

TURBO_TOKEN: ${{ secrets.TURBO_TOKEN }}

TURBO_TEAM: ${{ secrets.TURBO_TEAM }}

For Nx, similar gains come from computation caching (local and remote). The important concept is the same: cache keys are derived from inputs (code, configs, env) and restore outputs when inputs match.

3) Deployment: “prune” what you ship

Large monorepos often benefit from producing a minimal deployable subset:

- Build only the target app and its dependencies

- Avoid shipping unrelated packages

This helps keep deploy artifacts smaller and deployments more predictable.

4) CI guardrails that improve quality with positive friction

A few guardrails that pay back quickly:

- Block deep imports across packages (public API only)

- Enforce architectural boundaries (especially with shared packages)

- Require typecheck on PRs touching public APIs

- Run Storybook/visual checks when UI packages change (optional but powerful)

These are “friendly constraints” that make scaling safer.

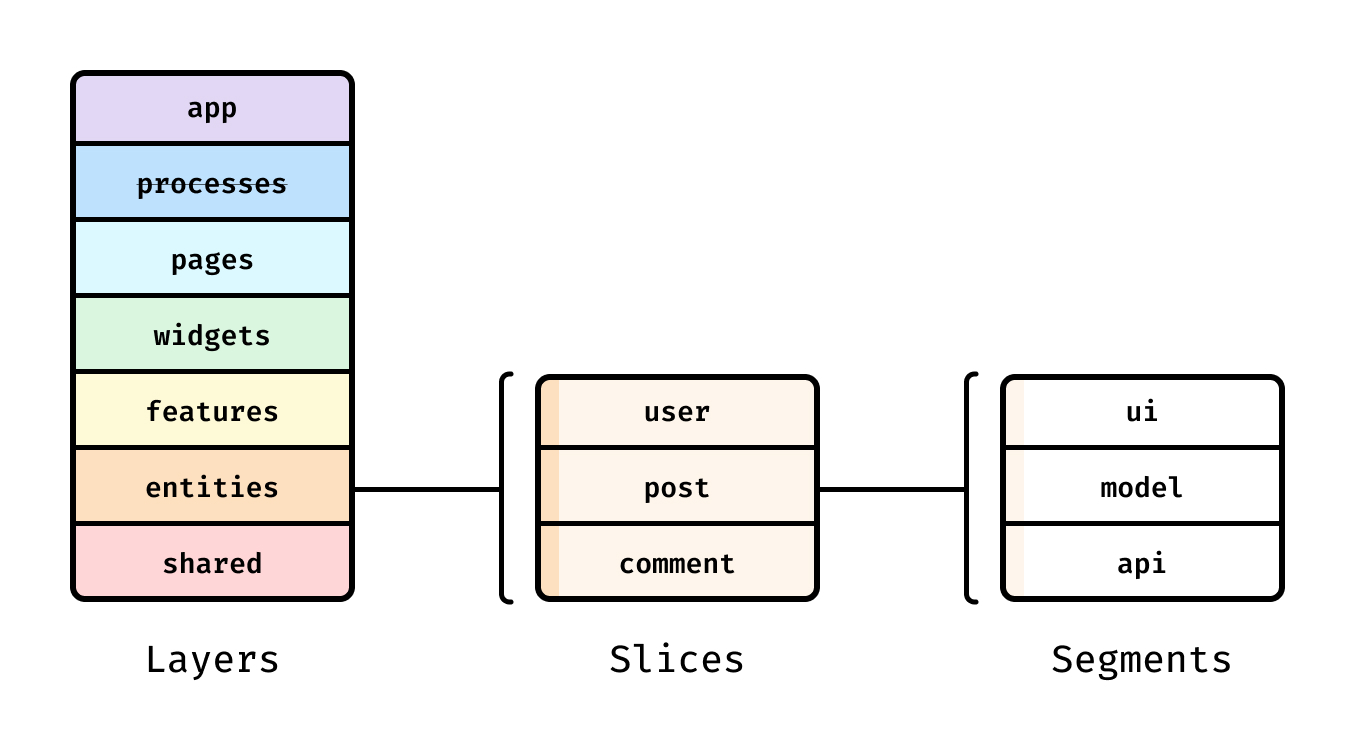

Where Feature-Sliced Design fits: architecture inside apps and packages

Most monorepo advice stops at tooling. That's necessary—but not sufficient. The long-term success factor is how code is structured inside each app and how shared modules are designed.

Feature-Sliced Design (FSD) is a community-driven methodology (see feature-sliced.design) that helps teams build frontend systems with:

- Clear layers and dependency direction

- Predictable slice boundaries

- Explicit public APIs

- Architectural consistency across apps and teams

As demonstrated by projects using FSD, consistent slicing reduces onboarding time and refactoring risk because developers can predict where code lives and how it can be imported.

FSD inside a monorepo: the “best of both worlds”

A productive pattern is:

- Use the monorepo to share packages (UI kit, API clients, shared tooling)

- Use FSD to structure code inside each app and shared domain package

Example:

apps/web/src/ app/ pages/ widgets/ features/ entities/ shared/

packages/ui/src/ shared/ # design tokens, ui primitives widgets/ # optional, if your UI kit includes composite widgets index.ts

packages/domain-sales/src/ features/ entities/ shared/ index.ts

The win: you avoid a “global shared folder” that becomes a dumping ground. Instead, shared is scoped and structured.

Public API and slices: the scaling mechanism

FSD encourages explicit public APIs at slice boundaries. Combine that with monorepo package exports and you get a clean layered system:

- App imports from package public APIs

- Packages expose public APIs per slice (or per layer)

- Internal files remain internal

This strongly reduces accidental coupling—the silent killer of large codebases.

Compare approaches (table, max 3 columns)

| Approach | Strength in frontend systems | Risk in large monorepos |

|---|---|---|

| MVC/MVP | Clear separation for UI + state in small apps | Often doesn’t encode feature boundaries; “model” grows into a blob |

| Atomic Design | Strong language for UI components and design systems | Can over-focus on UI atoms; domain logic placement becomes inconsistent |

| Feature-Sliced Design (FSD) | Clear dependency direction, feature boundaries, scalable slicing | Requires adopting conventions and enforcing public APIs consistently |

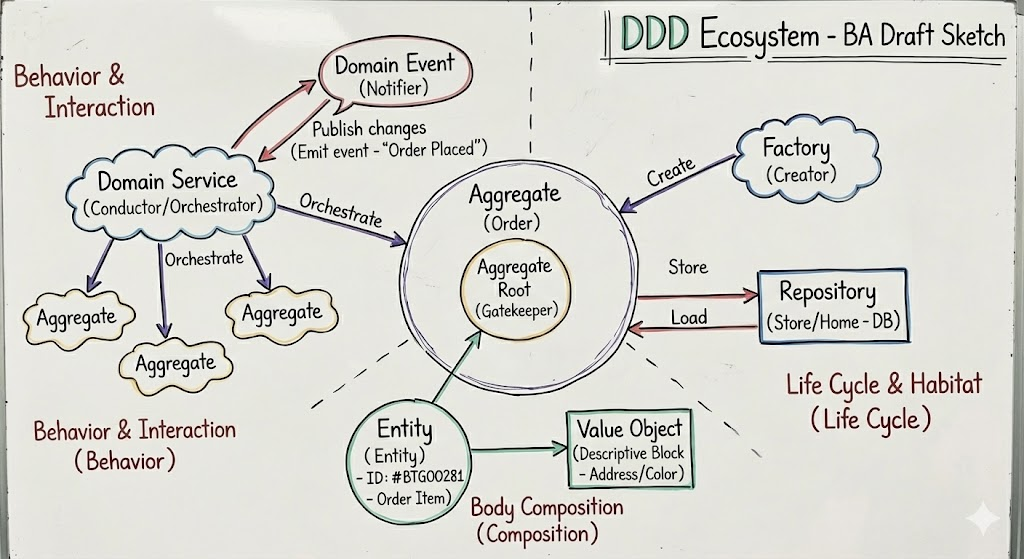

How FSD complements DDD without becoming abstract

Domain-Driven Design introduces useful ideas like bounded contexts and ubiquitous language. But frontend teams often struggle to translate those ideas into a file system that stays practical.

FSD helps by providing a concrete project structure that maps well to domain concepts:

entities/→ core domain concepts and their UI/state representationsfeatures/→ user-facing capabilities (checkout, search, onboarding)shared/→ reusable primitives (ui, lib, api, config)

This makes “domain boundaries” visible in imports and directories—not just in documents.

A practical FSD rule set for monorepos

Start with these rules (they scale well):

- Apps don’t import deep internals of packages; only from public APIs.

- Features don’t import other features unless there is a deliberate shared slice.

- Keep

shared/in packages small and explicit (primitives, not business flows). - Prefer extracting a new package when a domain becomes multi-app and high-change.

These rules improve modularity, reduce regressions, and make refactoring feel safe.

Common frontend monorepo problems and proven fixes

A frontend monorepo succeeds when you aggressively prevent the predictable failure modes. Here are the most common ones and practical solutions.

Problem 1: “Shared” becomes a dumping ground

Symptom: everything ends up in shared/, and no one knows what’s safe to reuse.

Fix: make reuse intentional

- Adopt FSD layers to classify modules (shared/entities/features).

- Require a public API file (

index.ts) for every reusable slice/package. - Add lightweight documentation for shared packages: purpose, consumers, stability.

Problem 2: Deep imports create hidden coupling

Symptom: refactors break random apps because they import internal files.

Fix: enforce public APIs

- Export only what’s supported.

- Use

package.json exports(for packages) and ESLint rules (for slices). - Treat “deep import” as a build-breaking violation.

Problem 3: CI becomes slow and expensive

Symptom: every PR runs everything, and caching isn’t effective.

Fix: graph-aware execution + caching

- Adopt Turborepo pipelines or Nx affected builds.

- Cache build outputs properly (define

outputs). - Use remote caching when CI is a bottleneck.

A positive outcome you can expect: faster feedback loops and calmer releases.

Problem 4: Breaking changes propagate without coordination

Symptom: shared package changes break consumers; teams lose trust.

Fix: add contracts and ownership

- Define ownership with

CODEOWNERS. - Require review for public API changes in shared packages.

- Keep changelogs or release notes for shared modules (even internal ones).

Problem 5: Inconsistent structure across apps increases onboarding time

Symptom: each app is organized differently; new engineers feel lost.

Fix: standardize with FSD + scaffolding

- Adopt one structure across apps (FSD layers and naming).

- Provide templates or generators (Nx can help; otherwise simple scripts).

- Keep “how to add a feature” docs short and concrete.

This builds confidence and autonomy in teams.

Migration plan: move to a frontend monorepo without stopping delivery

If you already have multiple repos, you can migrate without a big-bang rewrite. The goal is steady progress with low risk.

Step 1: Start with a “shell monorepo” and move one app

- Create the workspace structure (

apps/,packages/, root configs). - Move one app into

apps/web. - Keep it deployable early to maintain confidence.

Step 2: Extract shared code as packages, not copy-paste

- Identify shared UI/components or domain helpers.

- Extract them into

packages/uiorpackages/shared. - Replace duplicates with

workspace:*dependencies.

Step 3: Add a build pipeline and make CI green

- Introduce Turborepo or Nx.

- Make

lint/test/buildrun at the root. - Add caching only after outputs are correct (cache correctness beats cache speed).

Step 4: Introduce architectural boundaries gradually (FSD is ideal here)

- Start by adopting FSD structure in the most active app.

- Add import rules to prevent forbidden dependencies.

- Expand to other apps as they change.

Step 5: Improve developer experience once the system is stable

- Centralize configs (ESLint, TS, Prettier).

- Add generators/templates for features.

- Document the public APIs and boundary rules.

This approach turns migration into a positive momentum project, not a productivity freeze.

Conclusion

A frontend monorepo can be a long-term advantage in 2025 when it’s treated as a modular system: clear boundaries, explicit public APIs, strict dependency hygiene, and graph-aware CI/CD. Tooling like pnpm workspaces, Turborepo, Nx, and Lerna can accelerate builds and reduce operational overhead, but the biggest wins come from architecture—keeping coupling low, cohesion high, and ownership clear. Adopting a structured methodology like Feature-Sliced Design (FSD) is a practical investment in code quality, refactoring safety, and faster onboarding across teams.

Ready to build scalable and maintainable frontend projects? Have questions or want to share your experience?

Dive into the official Feature-Sliced Design Documentation to get started.

Disclaimer: The architectural patterns discussed in this article are based on the Feature-Sliced Design methodology. For detailed implementation guides and the latest updates, please refer to the official documentation.