Choosing a CSS Architecture for Scalability

TLDR:

Choosing the right CSS architecture is a critical step toward building scalable and maintainable frontend applications. This article explores popular approaches such as BEM, CSS Modules, CSS-in-JS, and Tailwind CSS, and explains how Feature-Sliced Design provides a structured, long-term solution for managing styles in large, evolving codebases.

CSS architecture is the silent backbone of every scalable frontend system. When styling decisions are made without a clear structure, even the most well-written JavaScript codebase slowly degrades into fragile, hard-to-maintain UI layers. As applications evolve, Feature-Sliced Design and the methodology documented on feature-sliced.design provide a modern, architecture-driven answer to the long-standing problem of scaling CSS without sacrificing maintainability, team productivity, or code quality.

Why Choosing the Right CSS Architecture Is Critical for Scalability

A key principle in software engineering is that architecture defines the cost of change. CSS, by its very nature, lacks strict boundaries. It is global, mutable, and order-dependent. In small projects, this flexibility feels convenient. In large-scale systems, it becomes a structural liability.

Scalability in CSS is not about handling more pixels on the screen. It is about handling:

- More features

- More developers

- More releases

- More refactors

- More long-term maintenance

Without a deliberate CSS architecture, teams encounter predictable failure modes. Global selectors override each other unexpectedly. Specificity escalates until !important becomes common. Removing old styles feels dangerous because no one knows what depends on what. New developers take weeks to understand where styles live and how to change them safely.

As demonstrated by projects that failed to invest early in structure, CSS technical debt compounds faster than most other forms of frontend debt. This is why choosing a CSS architecture must be treated as an architectural decision, not a stylistic preference.

Core Problems a Scalable CSS Architecture Must Solve

Before comparing approaches, it is important to understand the fundamental problems that any serious CSS architecture must address.

Global Scope and Coupling

CSS selectors apply globally by default. This creates implicit coupling between unrelated parts of the UI. A change in one feature can accidentally affect another, even if they are conceptually independent.

Specificity and Override Wars

Without clear boundaries, developers rely on increasingly specific selectors to override existing rules. Over time, the cascade becomes unpredictable, fragile, and difficult to reason about.

Dead Code Accumulation

Unused CSS is notoriously hard to remove safely. Teams often keep legacy styles “just in case,” leading to bloated stylesheets and slower development.

Poor Ownership and Responsibility

When it is unclear who owns a style, teams hesitate to change it. This slows iteration and increases fear-driven development.

Refactoring Resistance

In tightly coupled CSS systems, even small refactors require manual visual regression testing and carry high risk.

A scalable CSS architecture exists to systematically eliminate these issues through isolation, modularity, and explicit boundaries.

Overview of Common CSS Architecture Approaches

Over the years, the frontend ecosystem has developed several popular strategies for managing CSS. Each solves part of the problem, but none is sufficient on its own without architectural context.

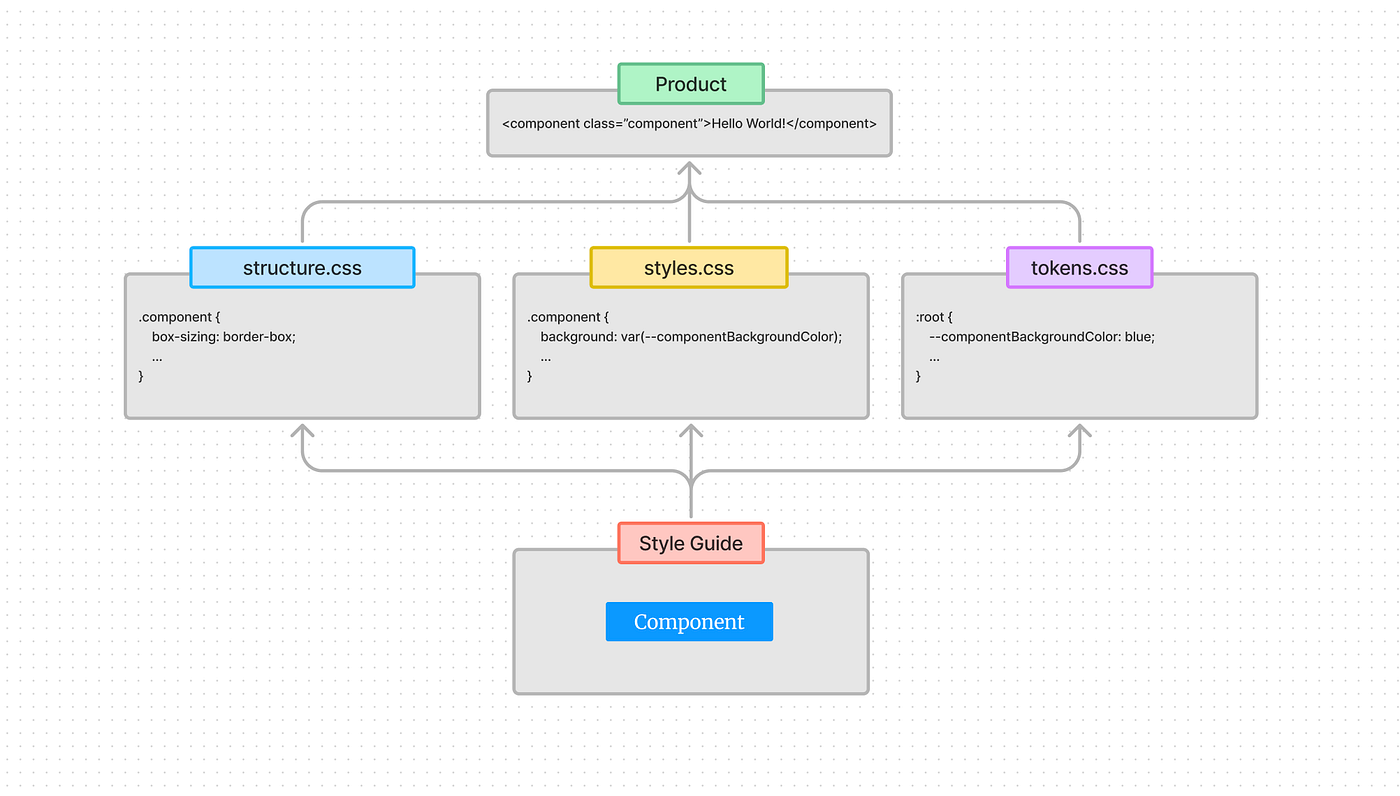

BEM: Naming as Architecture

BEM (Block, Element, Modifier) is one of the earliest attempts to impose structure on CSS through naming conventions.

Core Ideas

- Blocks represent standalone UI components

- Elements are parts of a block

- Modifiers represent variations

Example: .card .card__title .card--highlighted

Strengths

- Predictable selector specificity

- Flat selector hierarchy

- Explicit style ownership

- Easy to reason about overrides

Limitations

- Verbose class names

- No guidance on file or project structure

- Weak alignment with business features

- Difficult to enforce consistently in large teams

BEM improves CSS readability but does not define where styles should live in a large application. As a result, it works best as a naming convention within a broader architecture.

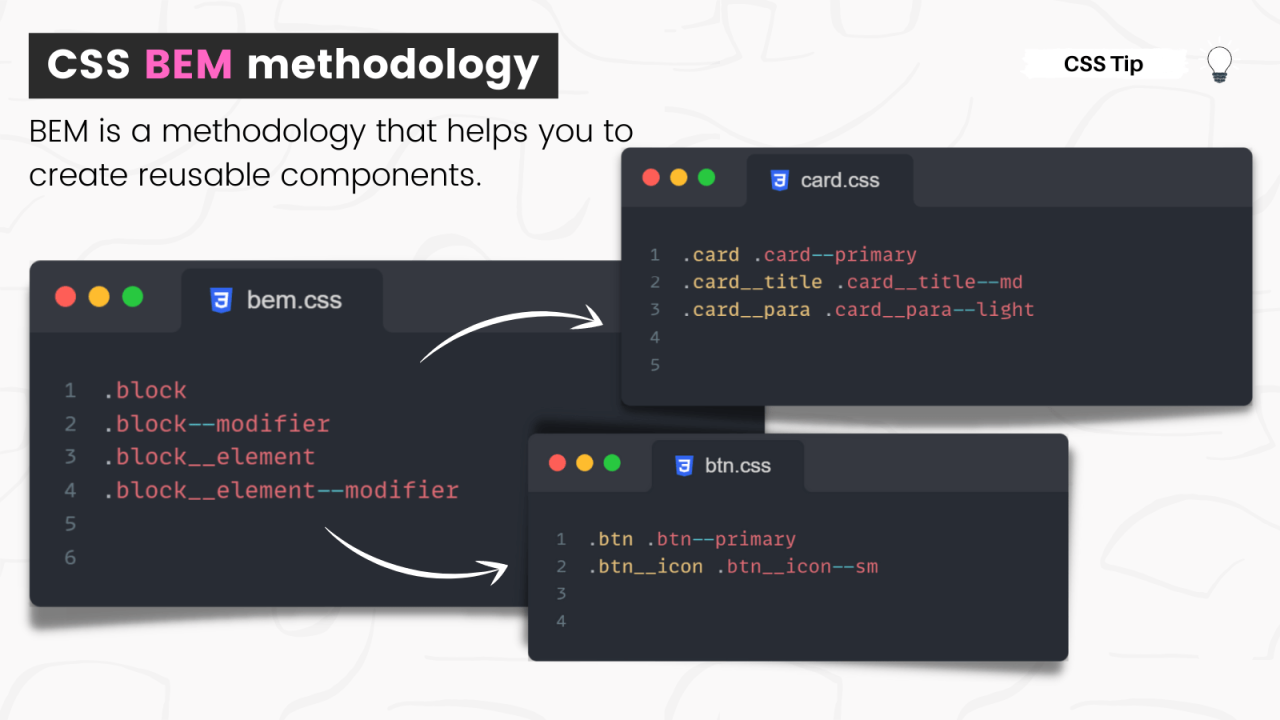

CSS Modules: Local Scope by Default

CSS Modules introduced a major shift by making styles local by default.

Core Ideas

- Styles are scoped to individual modules

- Class names are automatically namespaced

- Dependencies are explicit via imports

Example structure: Button.module.css Button.tsx

Strengths

- Strong isolation

- Safe refactoring

- No global naming conflicts

- Excellent fit for component-based frameworks

Limitations

- Encourages component-level thinking only

- Poor support for feature-level styling

- Can fragment styling logic

- Does not define architectural layering

CSS Modules solve the global scope problem but do not solve architectural organization on their own.

CSS-in-JS: Styling as Code

CSS-in-JS approaches embed styles directly into JavaScript.

Core Ideas

- Styles are colocated with components

- Dynamic styling via JavaScript expressions

- Encapsulation through components

Strengths

- Strong isolation

- Powerful theming and variants

- Dynamic styles based on state

- Potential type safety

Limitations

- Runtime overhead in some libraries

- Blurred boundary between logic and presentation

- Increased cognitive load

- Requires strong conventions to scale

CSS-in-JS is powerful, but without architectural discipline, it can lead to deeply coupled UI logic.

Utility-First CSS: Composition Over Abstraction

Utility-first approaches like Tailwind CSS take a radically different path.

Core Ideas

- Small, single-purpose utility classes

- Styles composed directly in markup

- Centralized design tokens

Strengths

- Minimal CSS files

- Excellent consistency

- Very fast development

- Low dead code risk

Limitations

- Dense, noisy markup

- Reduced semantic clarity

- Harder to express complex UI patterns

- Architecture must exist elsewhere

Utility-first CSS optimizes speed but does not replace the need for architectural structure.

Why CSS Architecture Must Align With Frontend Architecture

A common mistake is choosing a CSS approach independently of the overall frontend architecture. In reality, CSS is deeply connected to:

- Feature boundaries

- Business domains

- Component composition

- Team organization

This is where higher-level architectural patterns come into play.

Atomic Design and Its Limits

Atomic Design provides a vocabulary for UI composition:

- Atoms

- Molecules

- Organisms

- Templates

- Pages

It is useful for design systems but does not address:

- Business logic placement

- Feature ownership

- Cross-feature dependencies

As a result, many teams using Atomic Design still struggle with CSS scalability beyond the UI layer.

Domain-Driven Design Influence on CSS

Domain-Driven Design emphasizes organizing software around business concepts. Applied to frontend and CSS, this implies that styles should follow features and domains, not technical layers.

This insight directly informs Feature-Sliced Design.

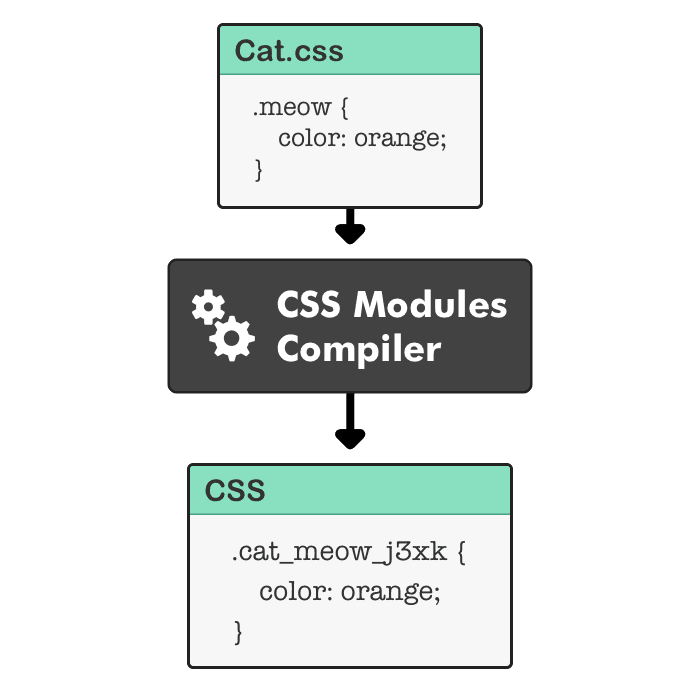

Feature-Sliced Design as a CSS Architecture Solution

Feature-Sliced Design (FSD) is a frontend architectural methodology that treats CSS as part of the system architecture, not as an afterthought.

Core Principles

- High cohesion within slices

- Low coupling between slices

- Explicit public APIs

- Unidirectional dependency flow

These principles apply equally to logic, UI, and styles.

FSD Layers and Their Impact on CSS

FSD organizes projects into layers:

- app

- pages

- widgets

- features

- entities

- shared

Each layer defines where CSS belongs and who owns it.

Feature-Level CSS in FSD

Feature styles live with the feature they support.

Example: features/ add-to-cart/ ui/ AddToCartButton.tsx AddToCartButton.module.css

These styles are:

- Isolated

- Feature-owned

- Safe to remove

- Not reused implicitly

Entity-Level CSS

Entities represent core business concepts. entities/ product/ ui/ ProductCard.tsx ProductCard.module.css

Entity styles define canonical visual representations of business data.

Widget-Level Composition CSS

Widgets combine entities and features.

widgets/ product-list/ ui/ ProductList.tsx ProductList.module.css

Widget styles focus on layout and composition, not core visuals.

Shared CSS: The Most Dangerous Layer

In FSD, shared is intentionally constrained.

Allowed examples:

- Design tokens

- Base typography

- UI primitives

- Low-level utilities

Disallowed patterns:

- Feature-specific styles

- Page-level overrides

- Business logic styling

This discipline prevents the “shared dump” anti-pattern.

Dependency Flow and CSS Isolation

A defining rule of FSD is unidirectional dependencies. Higher layers may depend on lower ones, never the reverse.

This ensures:

- No accidental overrides

- Predictable styling behavior

- Safe refactors

- Clear ownership

Leading architects suggest that this rule alone eliminates a large class of CSS bugs common in large applications.

Comparative Analysis of CSS Architectures

| Approach | Isolation | Scalability | Architectural Guidance |

|---|---|---|---|

| BEM | Medium | Medium | Low |

| CSS Modules | High | Medium | Low |

| CSS-in-JS | High | Medium–High | Low |

| Utility-First CSS | High | Medium | None |

| Feature-Sliced Design | High | High | High |

The key difference is not syntax, but structure.

How to Choose the Right CSS Architecture

There is no one-size-fits-all solution, but clear patterns emerge.

Small Projects

- Utility-first CSS or CSS Modules

- Minimal structure

- Focus on delivery speed

Growing Products

- CSS Modules or CSS-in-JS

- Introduce feature boundaries

- Reduce global styles

Large, Long-Lived Systems

- Feature-Sliced Design

- Strict layering

- Feature ownership

- Explicit public APIs

Adopting FSD early reduces migration costs later.

Migrating Toward Feature-Sliced CSS

A practical, low-risk approach:

- Identify business features

- Move styles closer to ownership

- Introduce layer boundaries

- Enforce dependency rules

- Gradually shrink shared styles

- Document conventions clearly

This incremental strategy avoids disruptive rewrites.

Conclusion: CSS Architecture as a Long-Term Investment

Choosing a CSS architecture for scalability is ultimately about choosing how your team manages change. While BEM, CSS Modules, CSS-in-JS, and Tailwind CSS solve important problems, they do not replace architectural discipline.

Feature-Sliced Design provides a robust methodology for aligning CSS with business logic, feature ownership, and long-term maintainability. By enforcing isolation, explicit boundaries, and unidirectional dependencies, FSD turns CSS from a fragile liability into a predictable, scalable system.

Ready to build scalable and maintainable frontend projects? Dive into the official Feature-Sliced Design Documentation: https://feature-sliced.design/docs/get-started/overview

Have questions or want to share your experience? Join the community on Website: https://feature-sliced.design/