Rollup.js: The Architect's Choice for Libraries

TLDR:

Learn why Rollup is the architect’s pick for JavaScript libraries: ES module-native tree-shaking, clean multi-format builds (ESM + CJS), and a practical plugin stack. See how Feature-Sliced Design turns public APIs and boundaries into a packaging contract that scales across teams.

Rollup is often the difference between a library that feels native in every consumer project and one that drags in avoidable bundle bloat, brittle build steps, and confusing module formats. By leaning into ES modules, tree-shaking, and a deliberate public API, Rollup helps you ship smaller, more predictable artifacts—especially when paired with a disciplined architecture like Feature-Sliced Design (FSD) from feature-sliced.design.

Why Rollup is the preferred bundler for JavaScript libraries

A key principle in software engineering is that interfaces should be stable and implementations should be replaceable. Libraries live and die by this principle: once published to npm, every breaking change in your packaging strategy becomes someone else’s fire drill.

Rollup’s core value proposition maps cleanly to library needs:

- Libraries need consumption flexibility, not a single “app bundle”.

- Consumers care about size, so dead code elimination must be reliable.

- Public APIs must be intentional, so your packaging should reinforce boundaries.

- Build artifacts should be predictable, so debugging and long-term maintenance stays pleasant.

Rollup positions itself around "superior dead code elimination" and code-splitting grounded in the module system. That emphasis matters more for libraries than for apps: libraries are embedded into unknown build pipelines (Webpack, Vite, Next.js, Remix, esbuild-based tools, custom configs), and your job is to produce artifacts that behave well everywhere.

Libraries are not apps: different constraints, different outputs

If you’re building an app, bundling “everything” can be acceptable. If you’re building a library, it’s usually a mistake.

A robust library build typically needs:

- ESM output for modern bundlers (best tree-shaking)

- CJS output for Node ecosystems and legacy tooling

- Type declarations (especially for TypeScript-first teams)

- Source maps for debugging

- Externalized dependencies so you don’t bundle React (or similar) twice

Rollup excels here because its model is fundamentally about taking a module graph and emitting multiple outputs with a clear, composable configuration surface.

The architect’s angle: coupling, cohesion, and artifacts

When architects evaluate a build tool, they’re not picking “the fastest bundler”. They’re picking a packaging contract.

Rollup pushes you toward good architectural hygiene:

- Low coupling: treat dependencies as external and let consumers manage versions.

- High cohesion: keep features and entities modular so exports remain meaningful.

- Explicit public API: publish what you want users to rely on—nothing more.

- Isolation: avoid side effects and hidden global state to keep tree-shaking trustworthy.

This is where Feature-Sliced Design becomes more than a folder convention: FSD is a methodology for containing complexity, especially in large codebases and multi-team environments. Its emphasis on slices and public APIs aligns naturally with how library entry points should work.

How Rollup's ES module-first pipeline makes tree-shaking actually work

Tree-shaking is not magic—it’s an outcome of static analysis. If the bundler can prove a symbol is unused and prove removing it won’t change runtime behavior, it can safely eliminate it.

Tree-shaking is not magic—it's an outcome of static analysis. If the bundler can prove a symbol is unused and prove removing it won't change runtime behavior, it can safely eliminate it.

Rollup's FAQs describe tree-shaking as "live code inclusion" that marks relevant statements and removes the rest. And the broader ecosystem recognizes that tree-shaking relies on the static structure of ES module syntax (import / export).

A mental model you can design for

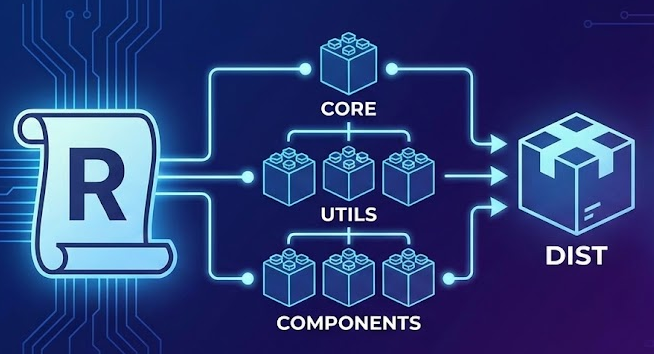

Here’s a practical, architect-friendly diagram (described):

- Parse modules into an AST (abstract syntax tree).

- Build the module graph from

import/export. - Mark reachable exports starting at your consumer’s entry point.

- Analyze execution paths to avoid removing side-effectful code.

- Remove unreachable statements (dead code).

- Render output (ESM/CJS/UMD/etc.) and optionally minify.

Rollup's core advantage for libraries is that it was built around this flow—meaning tree-shaking is not a "checkbox feature"; it's the design center.

Why ES modules beat CommonJS for library builds

CommonJS (require, module.exports) is dynamic. ES modules are static.

That one difference creates huge downstream effects:

- With ESM, bundlers can see imports/exports without executing code.

- With CJS, bundlers often have to assume worst-case behavior.

- ESM output composes better across tooling (modern app bundlers prefer it).

Even Webpack's own guide frames tree-shaking as relying on ES module syntax and notes Rollup popularized the concept.

Side effects: the silent tree-shaking killer

Tree-shaking is only safe when modules are free of unexpected side effects.

Common issues:

- Importing a file that mutates globals (e.g., polyfills,

windowmutations) - “Barrel” modules that execute code on import

- Top-level singleton initialization that shouldn’t run unless used

Actionable guidance:

- Keep modules pure by default.

- Treat side-effect files as explicit entry points (e.g.,

./polyfills). - Use

package.jsonsideEffectsresponsibly (common in the ecosystem) to help consumer bundlers reason about removals. - In Rollup, be deliberate with

treeshakesettings (more on that below).

In architectural terms: make dependencies explicit and minimize implicit behavior. This increases predictability, testability, and bundle efficiency—all at once.

A production-grade Rollup config for publishing libraries (ESM + CJS + types)

Search intent usually converges on one thing: “Show me the rollup config that produces ESM and CJS cleanly.” Let’s do it like an architect—starting from requirements, not from copy-pasted snippets.

Step 1: Decide your packaging strategy (single bundle vs preserve modules)

There are two common library output styles:

-

Single bundle per format

- Pros: fewer files, easy to consume

- Cons: can reduce fine-grained tree-shaking depending on how you export, and makes per-module debugging harder

-

Preserve modules (recommended for many component/utility libraries)

- Pros: keeps file boundaries, maximizes treeshake potential, maps well to subpath exports

- Cons: more files, requires a cleaner public API strategy

If your library has many independently used modules (icons, utilities, UI components), preserving modules often results in better consumer experience.

Step 2: Establish strict entry points (your public API)

Feature-Sliced Design calls public API a contract and a "gate" that only allows access through selected exports—often implemented as an index file that re-exports allowed modules.

This is exactly what a library entry point should be.

A common setup:

src/index.ts(main public API)- optionally

src/*/index.ts(sub-APIs if you intentionally support them)

Architectural rule of thumb:

- If it’s not in the public API, it’s not supported.

- Make internal modules importable only from within the library.

Step 3: Write a Rollup configuration that targets library outputs

Below is a practical rollup.config.mjs that demonstrates:

- dual output (ESM + CJS)

- source maps

- externals

- common plugins for real-world libraries

// rollup.config.mjs

import resolve from '@rollup/plugin-node-resolve';

import commonjs from '@rollup/plugin-commonjs';

import json from '@rollup/plugin-json';

import replace from '@rollup/plugin-replace';

import terser from '@rollup/plugin-terser';

import typescript from '@rollup/plugin-typescript';

import pkg from './package.json' assert { type: 'json' };

const external = [

...Object.keys(pkg.dependencies || {}),

...Object.keys(pkg.peerDependencies || {}),

];

export default [

{

input: 'src/index.ts',

external,

plugins: [

replace({

preventAssignment: true,

'process.env.NODE_ENV': JSON.stringify('production'),

}),

resolve({ browser: true }),

commonjs(),

json(),

typescript({ tsconfig: './tsconfig.build.json' }),

terser(),

],

output: [

{

dir: 'dist/esm',

format: 'esm',

sourcemap: true,

preserveModules: true,

preserveModulesRoot: 'src',

},

{

dir: 'dist/cjs',

format: 'cjs',

sourcemap: true,

exports: 'named',

preserveModules: true,

preserveModulesRoot: 'src',

},

],

},

];

Why these choices matter:

externalprevents bundling runtime dependencies into your library (critical for React, Vue, etc.).preserveModuleskeeps module boundaries for better treeshaking and clearer debugging.exports: 'named'makes CJS interop less surprising for consumers.sourcemapis non-negotiable for adoption in serious teams.

Rollup's configuration surface for output formats and related options is documented in its configuration options reference.

Step 4: Generate TypeScript declarations

Rollup builds JavaScript, but library consumers also want .d.ts. Typical approaches:

- Run

tsc --emitDeclarationOnlyintodist/types - Or bundle types using a dedicated plugin

A simple, reliable approach:

-

Create

tsconfig.build.json:declaration: trueemitDeclarationOnly: trueoutDir: "dist/types"

-

Add a build step:

tsc -p tsconfig.build.json

Architectural note: type generation is also part of your public API contract. If you re-export something, ensure the types follow.

Step 5: Make package.json consumption-proof

Modern consumers care about exports. Your library should clearly map ESM and CJS entrypoints:

{

"name": "@acme/design-system",

"version": "1.0.0",

"type": "module",

"main": "./dist/cjs/index.js",

"module": "./dist/esm/index.js",

"types": "./dist/types/index.d.ts",

"exports": {

".": {

"types": "./dist/types/index.d.ts",

"import": "./dist/esm/index.js",

"require": "./dist/cjs/index.js"

}

},

"files": ["dist"],

"peerDependencies": {

"react": ">=18"

}

}

Why architects prefer this:

- Explicit contracts for module resolution reduce “it works on my machine” issues.

- Conditional exports help Node/bundlers pick the right format.

- Peer dependencies prevent duplicate frameworks.

If you publish multiple entry points (e.g., @acme/ui/button), add subpath exports intentionally—don’t leak internals accidentally.

Essential Rollup plugins for library builds and how to choose them

Rollup stays intentionally minimal. It doesn’t assume how you want to resolve Node modules, transpile TypeScript, or consume CommonJS. That’s why the rollup plugins ecosystem is central to real projects.

Rollup's "tools" documentation explicitly discusses adding configuration for npm dependencies because Rollup doesn't handle them "out of the box".

The “critical path” plugins you’ll use in most libraries

Module resolution and interop

@rollup/plugin-node-resolve– resolves packages innode_modulesusing Node resolution rules@rollup/plugin-commonjs– converts CommonJS modules to ESM so Rollup can include them

Language and syntax

@rollup/plugin-typescript– basic TypeScript transpilation (often paired with separatetscfor declarations)@rollup/plugin-babel– when you need fine control over output targets or React transforms

Build ergonomics

@rollup/plugin-replace– replace environment flags for consistent builds@rollup/plugin-json– import JSON config/data safely

Optimization

@rollup/plugin-terser– minification for production bundles

The official Rollup plugins repository positions itself as a "one-stop shop" for plugins considered critical for everyday use.

Plugin ordering rules that prevent subtle bugs

Rollup plugin order is not cosmetic—think of it as a compilation pipeline:

replace(so downstream plugins see final constants)resolve(so imports locate correctly)commonjs(so CJS becomes analyzable)typescript/babel(so code becomes target-compatible)terser(only after code is finalized)

If tree-shaking feels “broken”, it’s often because a plugin introduced side effects or converted modules into a less analyzable shape too early.

A selection heuristic architects like

Use this quick rule:

- Prefer ESM dependencies and keep them external when possible.

- Only bring CJS into the bundle when you must.

- Use TypeScript primarily for types and developer experience; keep runtime output simple.

This reduces coupling to your build system and makes your library easier to maintain long-term.

Rollup config details that separate “working” from “professional”

You can absolutely ship a library with a minimal config. But professional libraries handle edge cases up front.

Externalization strategy: dependencies vs peerDependencies

A standard library approach:

- peerDependencies: frameworks and large shared runtimes (React, Vue, RxJS in some ecosystems)

- dependencies: small runtime helpers you truly need

- devDependencies: build-time tooling only

In Rollup, externalize both dependencies and peerDependencies by default for frontend libraries, unless you have a clear reason not to.

Why: bundling dependencies can cause version conflicts, duplicated runtimes, and larger consumer bundles. Reducing those risks improves adoption.

Output formats: ESM, CJS, and when (rarely) UMD matters

Most modern libraries need ESM + CJS. UMD/IIFE still matters when:

- You support script-tag usage (CDNs, legacy apps)

- You integrate into non-module environments

Rollup supports formats like umd and requires globals mapping for externals in those builds.

A compact comparison:

| Format | Best for | Watch out for |

|---|---|---|

| ESM | Modern bundlers, best tree-shaking | Ensure side effects are controlled |

| CJS | Node tooling, legacy ecosystems | Interop quirks with default/named exports |

| UMD/IIFE | Script tags, global usage | Requires output.globals, bigger surface area |

Treeshake controls you should know

Rollup tree-shaking is powerful, but you must align it with your code’s semantics:

- If modules are pure, tree-shaking is safe and effective.

- If modules run side effects at import time, bundlers must keep them.

Practical tactics:

- Avoid top-level initialization unless it’s truly required.

- Keep “setup” code in explicit functions.

- Export small, composable units.

- Consider

preserveModulesto keep per-file granularity.

The Rollup FAQ explains its marking/removal process at the statement level, which is why this discipline pays off.

Publishing a library without the “dual package” headaches

The ecosystem is in a long transition: ESM is the future, but CJS is not gone. That transition creates traps.

Common failure modes

- Consumers importing the wrong format (CJS picked in a bundler context)

- Mixed ESM/CJS semantics causing runtime errors

- Two copies of a dependency because of mismatched resolution

- Type declarations not matching runtime exports

Design for clarity: one intent, explicit entrypoints

Architectural best practice:

- Treat your ESM build as the primary build for bundlers.

- Provide CJS as a compatibility build.

- Use

exportsto routeimportvsrequire. - Keep both builds generated from the same source structure.

If you need different behavior between Node and browser, don’t rely on clever bundler guesses—make it explicit via entry points.

Subpath exports: scaling the API without leaking internals

If you want consumers to import directly:

@acme/ui/button@acme/ui/modal@acme/utils/date

Then structure your build to support it intentionally.

A clean pattern is:

- One top-level public API for “batteries included”

- A set of subpath exports for fine-grained imports

This pairs nicely with Rollup’s preserveModules output because your folder structure can map to export paths.

Rollup vs Webpack vs esbuild (and where Vite fits) for libraries

No bundler wins every scenario. Architects choose tools by constraints.

Here’s a practical comparison focused on library builds:

| Tool | Strength for libraries | Tradeoffs |

|---|---|---|

| Rollup | ESM-first bundling, strong tree-shaking, clean multi-format outputs | Plugin pipeline requires intentional setup |

| Webpack | Extremely flexible, handles many asset types, widely adopted | Library builds can become complex; configuration surface is larger |

| esbuild | Very fast builds, simple defaults | Some advanced library packaging patterns may require extra tooling |

A few decision rules:

- Choose Rollup when you publish reusable packages and want high-quality ESM artifacts.

- Choose Webpack when you ship a product with many non-JS assets and need deep customization.

- Choose esbuild when build speed is paramount and your output needs are straightforward.

And where does Vite land? In many setups, Vite’s production build leverages Rollup concepts and configuration patterns, which is why many teams use Vite for apps and Rollup-style output thinking for libraries.

Architecture meets bundling: boundaries that stay maintainable and tree-shakable

Bundling quality depends on architecture quality. If your codebase is tangled, no rollup config can save you.

The core architectural goals for library code are:

- Cohesion: modules represent single responsibilities

- Low coupling: minimal cross-module knowledge

- Isolation: internal implementation details stay internal

- Stable public API: exports are designed, not accidental

Why folder structure is an architectural tool, not decoration

Teams adopt patterns like MVC, MVP, Atomic Design, DDD, and FSD because humans need repeatable mental models.

Here’s a comparison (focused on large frontend codebases and library-style reuse):

| Approach | Organizing principle | Typical scaling pain in frontend libraries |

|---|---|---|

| MVC / MVP | Separate UI, logic, data roles | Often too coarse for feature-rich UI domains; boundaries blur as features grow |

| Atomic Design | UI composition hierarchy (atoms → pages) | Great for design systems, weaker for domain logic boundaries; can encourage “UI-first” coupling |

| Domain-Driven Design | Align code with domain concepts | Strong for business logic, but needs adaptation for UI layers and frontend composition |

| Feature-Sliced Design | Layers + slices + segments, guided dependencies | Requires discipline, but yields predictable modularity and safer refactors |

Notice what matters for bundling:

- If boundaries are clear, you can publish smaller entry points.

- If public APIs are explicit, you can tree-shake unused functionality safely.

- If dependencies are controlled, you avoid accidental cycles and side effects.

Feature-Sliced Design: making library packaging a first-class architectural concern

Feature-Sliced Design is explicit about three ideas that map directly to library publishing:

- Layers encode responsibility and allowed dependency direction.

- Slices group code by domain/feature boundaries.

- Public API acts as a gate—only selected exports are reachable externally.

This is powerful for libraries because it helps you answer:

- What are we actually exporting?

- What is internal and can change freely?

- How do we prevent consumers (and our own app code) from bypassing boundaries?

Rollup + FSD: a natural pairing

Rollup wants a clear module graph and predictable exports.

FSD encourages:

- Intentional entry points

- Isolated slices

- Minimal cross-layer coupling

Together, they make it easier to produce:

- tree-shakable ESM builds

- clean subpath exports

- stable contracts across teams

- faster onboarding (less “where does this belong?”)

As demonstrated by projects using FSD, consistent boundaries reduce refactor cost because changes are localized by design rather than by accident.

Step-by-step: building an FSD-friendly shared UI library with Rollup

Let’s make this tangible with a realistic example: a shared UI package used by multiple apps in a monorepo.

1) Define the slice boundaries

In FSD terms, a shared UI library typically lives in shared/ui and exposes components through a public API.

Example structure:

src/

shared/

ui/

button/

ui/

Button.tsx

index.ts # public API for button

modal/

ui/Modal.tsx

index.ts

index.ts # public API for shared/ui

index.ts # package public API

Key idea: each folder has a predictable purpose, and each slice can define what is exportable.

2) Implement public API “gates”

FSD's public API concept is commonly implemented as an index file that re-exports the intended surface.

Examples:

src/shared/ui/button/index.tsre-exportsButtonsrc/shared/ui/index.tsre-exportsbutton,modal, etc.src/index.tsre-exports fromshared/ui

This creates a controlled export surface and prevents accidental coupling to internal file paths.

3) Configure Rollup to preserve modules for maximal treeshaking

For a component library, preserving modules is often ideal:

- consumers can import only what they use

- bundlers can drop unused components cleanly

- source maps point to real source boundaries

The earlier rollup config example already shows preserveModules: true. The important addition for UI libs is being strict about externals:

- mark

react,react-dom, and any styling runtimes as peerDependencies - externalize them in Rollup

4) Publish subpath exports intentionally (optional, but powerful)

If you want:

import { Button } from '@acme/ui'- and also

import { Button } from '@acme/ui/button'

Then add exports:

{

"exports": {

".": {

"types": "./dist/types/index.d.ts",

"import": "./dist/esm/index.js",

"require": "./dist/cjs/index.js"

},

"./button": {

"types": "./dist/types/shared/ui/button/index.d.ts",

"import": "./dist/esm/shared/ui/button/index.js",

"require": "./dist/cjs/shared/ui/button/index.js"

}

}

}

This is where FSD’s predictable structure makes the mapping manageable instead of chaotic.

5) Validate the consumer experience

Before publishing:

- Install the package into a sample project using Webpack

- Install into a Vite project

- Test both ESM and CJS consumption paths

- Check that unused imports truly disappear in production builds

A positive adoption experience here is a competitive advantage: developers will recommend your library because it “just works”.

Troubleshooting: the most common Rollup pitfalls in library mode

Even strong configs hit edge cases. Here are high-signal fixes.

“Tree-shaking isn’t working”

Checklist:

- Are you outputting ESM (

format: 'esm')? - Are your modules side-effect free by default?

- Are you converting ESM into CJS too early?

- Are you importing from deep internal paths that bypass your intended public API?

Rollup can tree-shake effectively when code is written as ES modules and exports are free of side effects.

“CommonJS dependency breaks the build”

Use @rollup/plugin-commonjs and ensure it runs after node-resolve. The CommonJS plugin is explicitly designed to convert CJS modules to ES6 so they can be included in a Rollup bundle.

“My UMD build fails because of missing globals”

If you produce umd or iife, define output.globals for external imports—Rollup's configuration options describe this requirement.

“Consumers get two Reacts”

Usually caused by one of:

- React bundled into your output (didn’t externalize it)

- React declared as

dependencyinstead ofpeerDependency - Consumer bundler resolves a different React instance due to monorepo hoisting issues

Fix: peerDependency + Rollup external + consumer dedupe where needed.

Conclusion

Rollup remains a strong choice when you want library artifacts that are clean, tree-shakable, and format-flexible—especially when you treat packaging as an architectural contract rather than a build chore. A well-designed rollup config outputs ESM and CJS predictably, uses a focused plugin pipeline, and externalizes dependencies to keep consumer bundles healthy. The biggest multiplier, though, is structure: adopting a methodology like Feature-Sliced Design turns public APIs and boundaries into an everyday habit, reducing coupling and making refactors safer as teams scale.

Ready to build scalable and maintainable frontend projects? Dive into the official Feature-Sliced Design Documentation to get started.

Have questions or want to share your experience? Visit our homepage to learn more!

Disclaimer: The architectural patterns discussed in this article are based on the Feature-Sliced Design methodology. For detailed implementation guides and the latest updates, please refer to the official documentation.