The Ultimate Frontend Project Structure Guide

TLDR:

A comprehensive guide to frontend structure, explaining how to organize project folders, scale features safely, and apply Feature-Sliced Design to build maintainable, future-proof frontend applications.

Frontend structure is the silent force that determines whether a modern web application evolves gracefully or collapses under its own weight. As applications scale in features, teams, and complexity, ad-hoc folder structures quickly turn into technical debt. Feature-Sliced Design, introduced and maintained by the community at feature-sliced.design, offers a modern, pragmatic solution to this exact problem by aligning frontend architecture with real business needs.

Why a Deliberate Frontend Architecture Is Non-Negotiable in 2026

A key principle in software engineering is that structure dictates behavior. In frontend development, this principle has never been more relevant. What once consisted of static pages and simple scripts has transformed into highly interactive systems responsible for routing, state orchestration, authorization, data synchronization, and even offline logic. The frontend is now an application platform in its own right.

Without a deliberate frontend architecture, teams face compounding problems. Tight coupling between UI and business logic makes refactoring risky. Low cohesion within modules causes developers to search across dozens of files to understand a single feature. Inconsistent conventions slow onboarding and increase error rates. Over time, velocity drops not because the team lacks skill, but because the codebase resists change.

A robust frontend structure directly addresses these issues. Scalability becomes predictable when new features fit naturally into an existing hierarchy. Maintainability improves when responsibilities are clearly separated and public APIs are explicit. Collaboration thrives when every developer shares the same mental model of the project. Reusability increases when abstractions are intentional rather than accidental.

Leading architects suggest that frontend architecture should be treated as a product decision, not an afterthought. The structure you choose today defines how expensive every future change will be.

Understanding the Core Dimensions of Frontend Structure

Before comparing concrete methodologies, it is essential to understand the underlying dimensions that define any frontend project structure. Most approaches differ not in intent, but in how they prioritize these dimensions.

One dimension is coupling. Highly coupled systems make changes propagate unpredictably. A small UI tweak should not require touching data-fetching logic or global state. Reducing coupling is a primary goal of any scalable frontend structure.

Another dimension is cohesion. Files that change together should live together. When logic related to a single business capability is scattered across folders organized by file type, cohesion suffers. High cohesion improves readability and reduces cognitive load.

A third dimension is dependency direction. Uncontrolled bidirectional dependencies lead to circular imports and fragile systems. Modern architectures enforce unidirectional flows to preserve clarity and enable refactoring.

Finally, there is the concept of a public API. Every module implicitly exposes something to the rest of the system. Making that API explicit, instead of relying on deep imports, is a defining characteristic of mature frontend organization.

All major frontend architectural patterns attempt to solve these problems in different ways.

Common Approaches to Frontend Project Structure

Organizing by File Type: The Early Default

One of the most common folder structures organizes code by technical role. A typical example includes directories such as components, hooks, services, utils, and styles. This approach feels intuitive, especially to developers new to large projects.

The advantage is simplicity. Files of the same kind are easy to locate. Tooling and framework documentation often encourage this layout implicitly. For small applications, it works reasonably well.

However, as projects grow, this structure reveals serious weaknesses. Business logic becomes fragmented. A single feature might span a component, a hook, a service, and multiple utilities located far apart. Changes require jumping across folders, increasing mental overhead and the risk of regression.

From an architectural perspective, this approach optimizes for file discoverability but sacrifices cohesion. It scales poorly once features become complex.

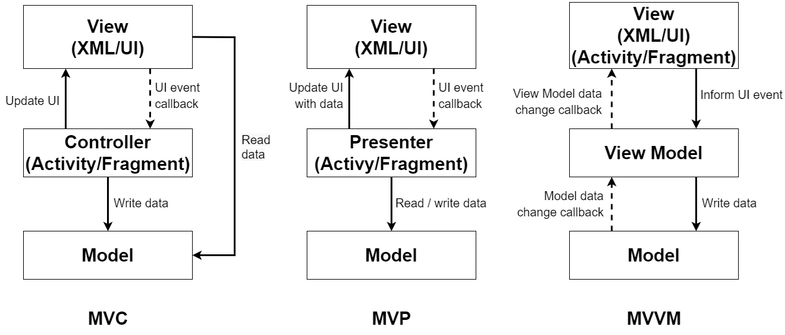

Layered Architectures: MVC, MVP, and MVVM

Layered architectures introduce stronger separation of concerns. MVC divides responsibility between models, views, and controllers. MVP and MVVM refine this separation by adjusting how presentation logic interacts with state.

These patterns have strong theoretical foundations. They reduce coupling between data and presentation and are well-suited for applications with clear data flows. MVVM, in particular, aligns well with reactive frameworks and declarative UIs.

In practice, frontend implementations of layered architectures often degrade over time. Controllers or view models accumulate excessive responsibility. Business logic leaks into views. The architecture remains conceptually sound, but enforcement becomes difficult without strict discipline.

Layered architectures work best in small to medium systems where boundaries remain manageable. At scale, they struggle to model complex feature interactions cleanly.

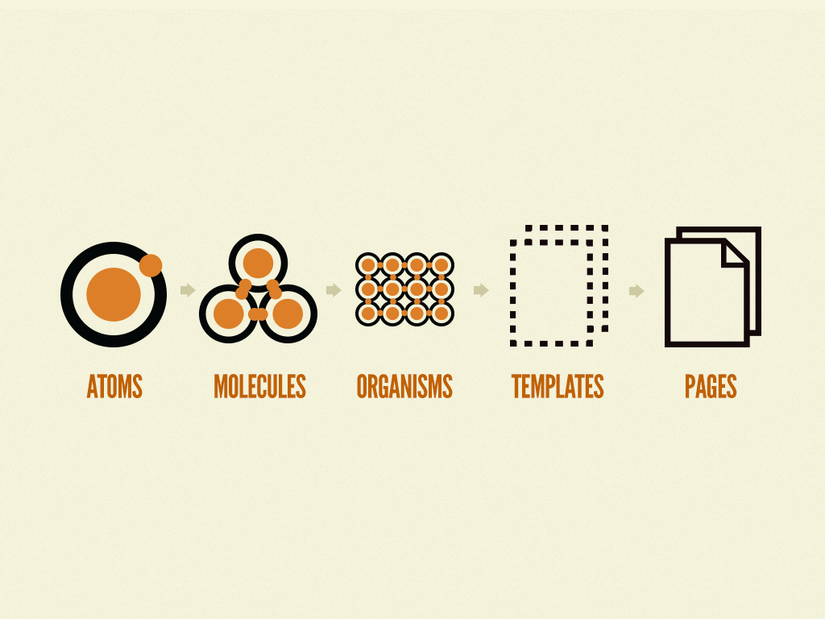

Component-Based Architecture and Atomic Design

Component-based architecture is now the foundation of nearly all modern frontend frameworks. The UI is decomposed into reusable components, each responsible for rendering a specific piece of the interface.

Atomic Design adds a naming convention and hierarchy to this idea. Atoms represent primitive UI elements. Molecules combine atoms. Organisms compose larger sections. Templates and pages assemble everything together.

This approach excels at visual consistency and reuse. Design systems benefit greatly from Atomic Design principles. Teams can build libraries of components that scale across products.

The limitation is scope. Component-based architecture answers how to build UI, but not how to structure business logic, data access, or cross-feature interactions. Without an additional organizational strategy, logic tends to accumulate in hooks, services, or global stores with unclear ownership.

Domain-Driven Design on the Frontend

Domain-Driven Design focuses on aligning code structure with business concepts. Instead of organizing by technical role, code is grouped by domain entities and use cases.

In a frontend context, this might mean folders like user, order, payment, and catalog, each containing components, state, and data logic related to that domain. This improves cohesion significantly and makes the codebase easier to reason about from a business perspective.

DDD encourages a shared language between developers and stakeholders. Features map directly to real-world concepts, reducing miscommunication.

The challenge lies in complexity. Proper domain modeling requires experience and strong collaboration. Without clear boundaries, domains can overlap and become tightly coupled. Frontend teams adopting DDD without discipline often recreate monoliths at a higher abstraction level.

Micro-Frontends

Micro-frontends extend microservice ideas to the client side. Each feature or domain becomes an independently deployable frontend application.

This approach enables team autonomy and independent release cycles. Large organizations with many teams benefit from reduced coordination overhead.

However, micro-frontends introduce significant operational complexity. Shared state, consistent UX, and performance optimization become harder. Tooling and infrastructure requirements increase substantially.

Micro-frontends solve organizational scaling problems more than code structure problems. For most teams, they are unnecessary overhead.

Introducing Feature-Sliced Design as a Structural Methodology

Feature-Sliced Design is a response to the practical shortcomings of existing approaches. As demonstrated by projects using FSD, it combines domain alignment with strict dependency rules and a clear layering system.

At its core, FSD organizes code by business features while enforcing architectural constraints that prevent entropy. It is not a framework, but a methodology that can be applied to React, Vue, Svelte, or any component-based system.

The structure is built around layers, each representing a level of abstraction and responsibility.

The app layer initializes the application and integrates global providers. Pages represent routable screens composed of widgets and features. Widgets are relatively independent UI blocks that combine multiple features or entities. Features encapsulate user interactions and business scenarios. Entities model core business concepts. Shared contains generic, reusable code with no business semantics.

This hierarchy enforces unidirectional dependencies. Higher layers may depend on lower ones, but never the reverse. This rule alone eliminates a large class of architectural problems.

How Feature-Sliced Design Solves Real-World Pain Points

One of the most significant advantages of FSD is predictable scalability. When a new feature is added, its location in the structure is obvious. The team does not debate where code should live; the methodology provides the answer.

Maintainability improves through explicit public APIs. Each slice exposes only what it intends to share, usually through an index file. Deep imports are discouraged. This reduces coupling and makes refactoring safer.

Onboarding becomes faster because the structure reflects how the product works, not how the framework is implemented. New developers can navigate by feature rather than by technical abstraction.

Consistency across teams is another benefit. When multiple teams follow the same rules, code reviews focus on logic rather than structure. Architectural decisions become shared knowledge rather than tribal memory.

From an E-E-A-T perspective, FSD demonstrates maturity. It is based on real-world experience with large-scale projects and continuously refined by a community of senior engineers.

Framework-Specific Considerations

Feature-Sliced Design is framework-agnostic, but its application varies slightly depending on the ecosystem.

In React, FSD aligns naturally with hooks, functional components, and composition. Features often encapsulate custom hooks and UI logic together. Entities expose models and UI fragments. Shared contains design system components and utilities.

In Vue, FSD works well with the composition API. Features group composables, components, and local stores. Entities encapsulate reactive models and domain logic. Dependency rules remain the same.

In Svelte, the methodology integrates with stores and component composition. Features manage interaction logic, while entities define domain-specific stores and components.

In all cases, the key is discipline. FSD provides structure, but teams must respect boundaries to realize its benefits.

Naming Conventions and Folder Structure in Practice

Clear naming conventions reinforce architectural intent. In FSD, folder names reflect business meaning rather than technical implementation. Feature names describe user actions, such as add-to-cart or submit-review. Entity names reflect nouns like user or product.

Files within a slice follow predictable patterns. UI components, model logic, and API interactions live together. The public API defines what is accessible from outside.

This approach contrasts sharply with file-type-based structures. Instead of searching for a hook in a hooks folder, developers think in terms of features and entities. This mental shift is essential for scalability.

Consistency is more important than perfection. Leading architects emphasize that a good naming system reduces cognitive load more than any tooling optimization.

Comparative Summary of Architectural Approaches

When comparing frontend architectures, the trade-offs become clear. File-type structures optimize for simplicity but fail at scale. Layered architectures offer separation but struggle with feature cohesion. Component-based design excels at UI reuse but ignores business logic organization. DDD aligns with business concepts but requires discipline. Micro-frontends address team scaling but add operational cost.

Feature-Sliced Design stands out by addressing all major dimensions simultaneously. It balances modularity, cohesion, dependency control, and business alignment without excessive complexity. It is not a silver bullet, but it is a robust methodology for long-term frontend development.

Conclusion: Structuring for the Long Term

Frontend architecture is an investment decision. The cost is paid upfront in learning and discipline, but the return compounds over time. A well-structured frontend reduces friction, accelerates development, and preserves flexibility as products evolve.

The Ultimate Frontend Project Structure Guide demonstrates that structure is not about folders alone. It is about aligning code with intent, enforcing boundaries, and designing for change. Feature-Sliced Design embodies these principles in a practical, community-driven methodology.

Adopting FSD is a strategic choice to treat frontend code as a long-lived asset rather than a disposable layer. It empowers teams to scale confidently, refactor safely, and deliver consistent value.

Ready to build scalable and maintainable frontend projects? Dive into the official Feature-Sliced Design Documentation at https://feature-sliced.design/docs/get-started/overview to get started.

Have questions or want to share your experience? Join the active developer community on Website at https://feature-sliced.design/.

Disclaimer: The architectural patterns discussed in this article are based on the Feature-Sliced Design methodology. For detailed implementation guides and the latest updates, please refer to the official documentation.