The 5 Frontend Architectures You Must Know in 2025

TLDR:

This guide highlights the 5 key frontend architectures every developer must know in 2025 and explains how to choose the right one for any project. It also shows why Feature-Sliced Design is emerging as the leading approach for building scalable, maintainable frontend applications.

Frontend architecture is the indispensable blueprint for creating a scalable, maintainable, and high-performance web application. As projects grow in complexity, avoiding spaghetti code and brittle UI architecture becomes a primary challenge, and a well-defined structure like Feature-Sliced Design from feature-sliced.design provides a robust methodology for managing this complexity. This guide explores the critical frontend patterns and organization strategies that leading architects and tech leads are leveraging to build resilient systems and exceptional developer experiences in 2025.

Why a Deliberate Frontend Architecture is Non-Negotiable in 2025

In the early days of the web, a “frontend” was mostly a handful of templates and some progressive enhancement.

Today, modern Single Page Applications (SPAs) and micro-frontend platforms act as full-fledged client-side applications: they handle routing, networking, caching, state management, domain logic, accessibility, and real-time updates.

Without a deliberate frontend structure, this quickly leads to:

- tightly coupled components;

- unpredictable side effects;

- duplicated logic across screens;

- slow onboarding and painful refactoring.

A key principle in software engineering is “structure first, complexity later.” If you don’t intentionally design your frontend system architecture, the structure emerges accidentally from hundreds of local decisions made under delivery pressure.

What do we actually mean by “frontend architecture”?

At a practical level, frontend architecture answers a few core questions:

- How do we organize code (folders, files, boundaries)?

- Where do we put business rules vs. presentation logic?

- How do modules depend on each other (or not)?

- What is the public API of each part of the UI?

- How do we align technical structure with business domains?

Think of architecture as the map of your codebase:

- Modules are regions.

- Public APIs are the borders and customs.

- Dependency rules are the flight paths between regions.

A good map makes it obvious where things belong and what is allowed to talk to what.

Symptoms of weak or missing frontend architecture

If any of these resonate, your architecture is already a bottleneck:

- A simple change in one feature breaks an unrelated screen.

- You hesitate to refactor because “it might blow up everything.”

- Components import “from everywhere,” mixing hooks, services, and utilities from random paths.

- There is no clear answer to: “Where should I put this new feature?”

- Junior developers struggle to find where logic lives, slowing down onboarding for months.

These are signs of high coupling (modules depend on too many details) and low cohesion (modules contain unrelated responsibilities), both of which make the codebase fragile.

Why architecture is a scaling multiplier

A deliberate UI architecture brings long-term benefits that compound over time:

-

Scalability

You can add new features without rewriting core parts. Boundaries and dependency rules prevent chaos when requirements change. -

Maintainability

Each module has a clear, focused purpose (high cohesion) and minimal knowledge about others (low coupling). This keeps refactors localized and safe. -

Team autonomy

Clear frontend organization allows multiple teams to work on separate features without constantly stepping on each other’s toes. -

Reusability and consistency

Shared modules (design system, domain entities, utilities) are easy to discover and consume through stable public APIs.

As demonstrated by projects using Feature-Sliced Design, teams that invest in architecture early can sustain growth for years without “big rewrite” phases. Instead of periodically throwing everything away, they continuously evolve their structure.

The 5 Core Frontend Architectures to Master

There is no single “perfect” frontend architecture. Leading architects choose patterns that fit their team, product lifecycle, and constraints.

In 2025, there are five architectures you should understand deeply:

- Layered architecture (MVC, MVP, MVVM)

- Component-based architecture & Atomic Design

- Micro-frontends

- Domain-Driven Design (DDD) for the frontend

- Feature-Sliced Design (FSD)

You will often combine these patterns rather than pick exactly one. For example, a micro-frontend platform that uses an FSD structure inside each micro-app and employs atomic components for the design system.

Let’s look at each in turn.

1. Layered Architecture (MVC, MVP, MVVM)

Layered architecture is one of the oldest and most recognizable models. It structures applications by technical responsibility:

- data and domain rules;

- presentation logic;

- rendering and user interaction.

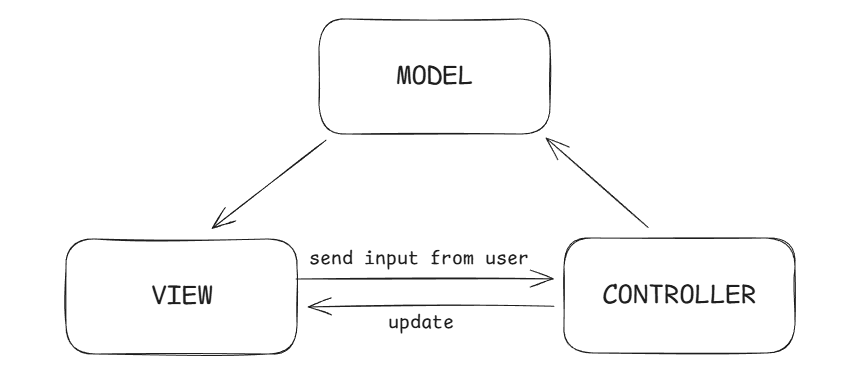

Three popular variants are:

-

Model–View–Controller (MVC)

- Model – data structures and business rules.

- View – renders UI based on model data.

- Controller – receives user input, triggers model updates, and re-renders views.

-

Model–View–Presenter (MVP)

The Presenter acts as a mediator, encapsulating UI-specific logic and orchestrating interactions between View and Model. Views tend to be “passive” and forward user events. -

Model–View–ViewModel (MVVM)

The ViewModel exposes reactive state and commands to the View (often via bindings or hooks). This is common in Angular, Vue, and even React with state containers.

A typical layered directory structure might look like:

src/

models/

user.ts

product.ts

views/

ProductListView.tsx

ProductDetailsView.tsx

controllers/

ProductController.ts

services/

apiClient.ts

Strengths

- Clear separation of concerns by role (data vs. logic vs. UI).

- Easy to explain to new developers because it mirrors textbook diagrams.

- Works well for small to medium-sized apps with straightforward flows.

Common pitfalls

- In larger SPAs, controllers or view-models often become “God objects” that know about everything: routing, orchestration, caching, error handling, UI state.

- Boundaries are by technical type rather than business concept. Features end up scattered across

models/,views/,controllers/with weak cohesion. - Reuse across domains is hard because code is tightly tied to specific flows handled by controllers.

When to consider a layered architecture

- Single-team applications with limited domain complexity.

- Legacy codebases where MVC/MVP are already established and full rewrites are unrealistic.

- Early phases of a product when you need a simple mental model and limited team size.

Layered patterns are valuable, but on their own they are rarely enough for long-lived, large-scale frontends.

2. Component-Based Architecture & Atomic Design

Modern frameworks like React, Vue, Solid, and Svelte are all fundamentally component-centric. Components encapsulate:

- markup and styling;

- local state;

- behavior tied to a part of the UI.

Atomic Design, introduced by Brad Frost, structures a component system into five levels:

- Atoms – the smallest building blocks (buttons, inputs, icons).

- Molecules – simple combinations of atoms (search field + button).

- Organisms – more complex UI sections (header, footer, product card grid).

- Templates – page-level layouts using organisms.

- Pages – concrete instances of templates with real data.

A design-system-oriented structure might look like:

src/

shared/

ui/

atoms/

Button/

index.tsx

Input/

index.tsx

molecules/

SearchField/

index.tsx

organisms/

Header/

index.tsx

Strengths

- Encourages reusability and visual consistency across the app.

- Well-suited to building and maintaining a design system or UI kit.

- Easy to align designers and developers around a shared UI vocabulary.

Limitations

- Atomic Design focuses heavily on visual hierarchy, not on domain logic or cross-cutting behaviors like state management or caching.

- Feature logic may still end up sprinkled across many components with implicit coupling.

- Without additional architectural rules, teams can still fall into the trap of “everything can import everything.”

Component-based architecture is foundational. Every modern frontend uses it. But to handle complex domain rules, you need an additional layer of architecture on top.

3. Micro-Frontends

Micro-frontends bring the microservices idea to the browser. Instead of one monolithic SPA, you have a set of independently deployable micro-apps that together form the product.

Each micro-frontend typically owns:

- its own routing segment;

- its own state and data fetching;

- its own release cycle and CI/CD pipeline.

Common integration approaches include:

- Build-time integration – Webpack module federation, shared libraries, static composition during build.

- Run-time integration – loading micro-apps via iframes, web components, or JavaScript manifests at runtime.

- Edge or server-side composition – server assembles HTML from multiple micro-frontends.

A micro-frontend directory layout (inside one micro-app) might still use internal architecture patterns:

packages/

catalog-app/

src/

app/

pages/

widgets/

features/

entities/

shared/

cart-app/

src/...

shell/

src/...

Strengths

- Team autonomy: Each team can deploy independently, choose tailored tooling, and scale work without centralized bottlenecks.

- Incremental migration: Legacy apps can be replaced piece-by-piece by new micro-frontends.

- Organizational alignment: Architecture mirrors the organizational structure (Conway’s law), which can be beneficial at scale.

Trade-offs

- Operational complexity: multiple pipelines, versioning, and monitoring setups.

- UX consistency risk: inconsistent design, routing, and behavior if teams are not aligned.

- Shared state and cross-app communication are non-trivial and often require additional infrastructure.

When micro-frontends shine

- Large enterprises with many teams and domains (banking platforms, marketplaces, super-apps).

- Situations where independent deployment and technology choice outweigh architectural overhead.

- Long-lived products needing gradual, low-risk migrations between stacks.

Micro-frontends solve organizational and deployment problems, but they don’t fully answer how to structure the code inside each micro-app. That’s where patterns like FSD become critical.

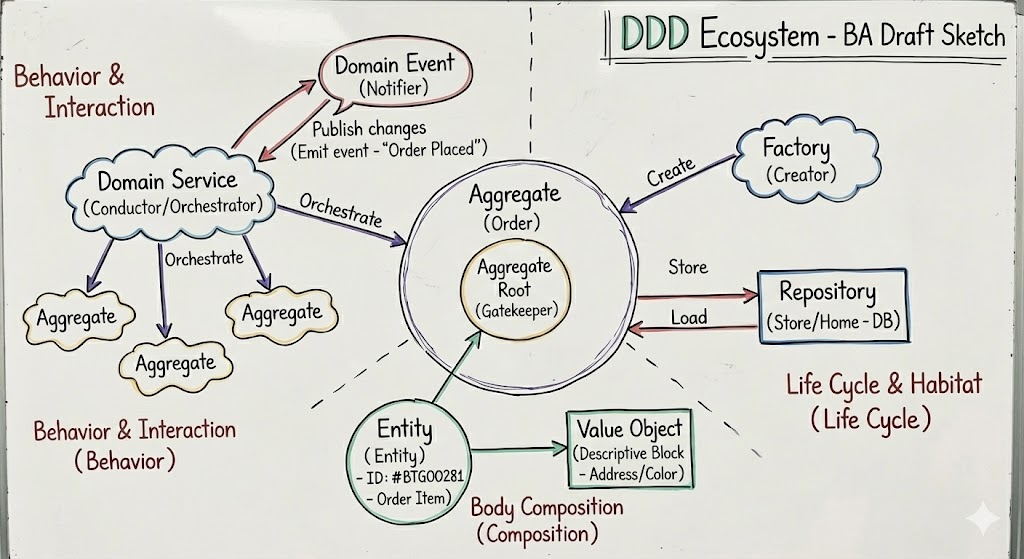

4. Domain-Driven Design (DDD) for the Frontend

Domain-Driven Design (DDD) proposes that software should mimic the business domain, not generic technical layers. Concepts like bounded context, aggregates, and ubiquitous language encourage strong alignment between code and business terminology.

Bringing DDD into the frontend means:

- Grouping code by business capabilities (e.g., Payments, Catalog, Authentication) instead of

components/,services/,hooks/. - Keeping all UI, state, and interactions for a domain close together.

- Making boundaries explicit so that contexts integrate via clear contracts and not the global state soup.

A DDD-inspired frontend structure might look like:

src/

domains/

catalog/

components/

hooks/

services/

model/

checkout/

components/

hooks/

services/

model/

shared/

ui/

api/

config/

Advantages

- High cohesion: each domain folder contains everything needed to implement that business capability.

- Easier communication with stakeholders because code mirrors real-world concepts.

- Better isolation of breaking changes: a change in the Catalog domain rarely leaks into Checkout if boundaries are maintained.

Challenges

- Requires a solid understanding of the business and its boundaries. Misidentified contexts lead to awkward dependencies.

- Without additional rules, there can still be intra-domain chaos (e.g.,

components/becoming a junk drawer). - Not every product has clear, stable domains from day one.

DDD principles are powerful, especially in complex business-heavy applications. Feature-Sliced Design expands and systematizes many of these ideas specifically for frontends.

5. Feature-Sliced Design (FSD): The Modern Blueprint

Feature-Sliced Design (FSD) is a frontend architecture methodology created specifically to address the challenges of large, evolving SPAs and multi-team development.

It combines:

- feature orientation (like DDD);

- layered thinking (like classic architectures);

- component-based composition (like Atomic Design);

- explicit dependency rules and public APIs.

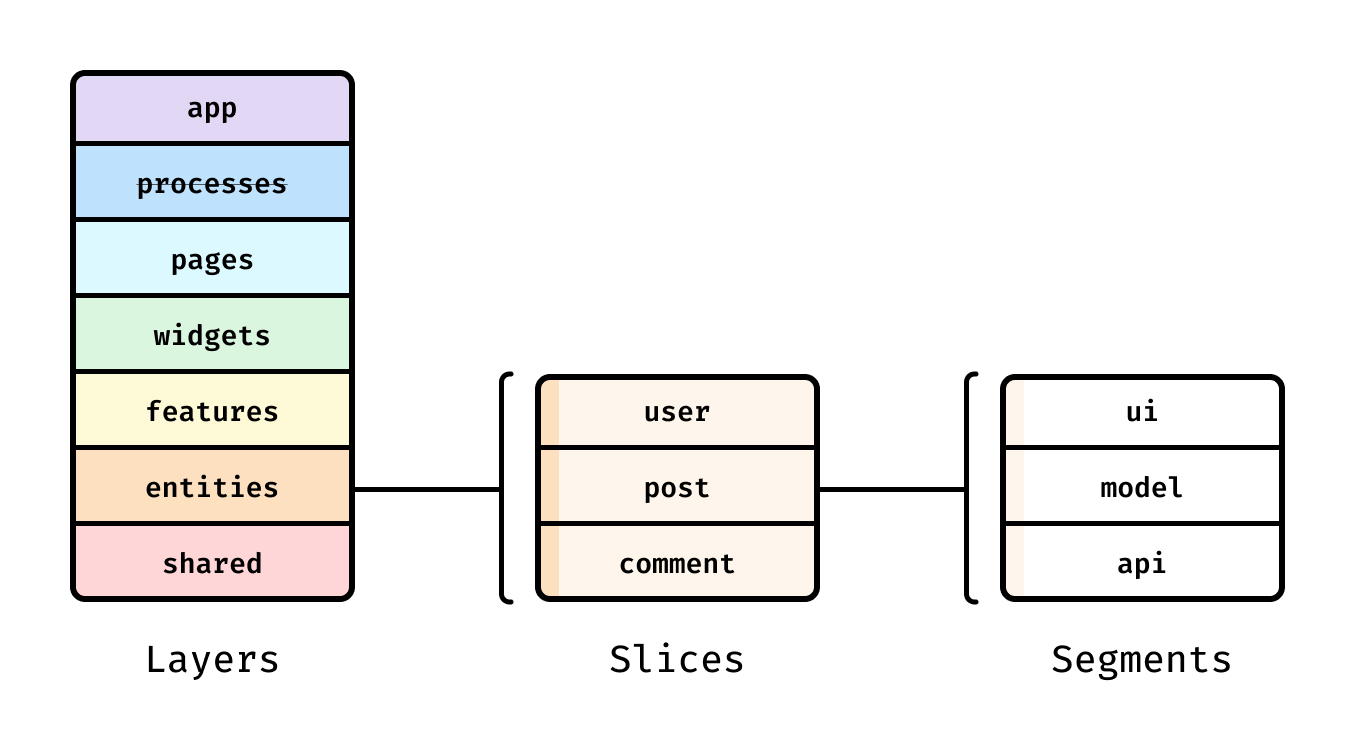

At a high level, FSD decomposes the app along two axes:

- Layers – vertical “strata” that define responsibility and dependency rules.

- Slices – horizontal segments grouped by business feature or entity.

A typical FSD-based project is organized as:

src/

app/ # app bootstrap, configuration, global providers, routing

processes/ # cross-page business flows (checkout flow, onboarding)

pages/ # routing-level pages composed from widgets and features

widgets/ # page sections that connect features and entities

features/ # user-level interactions (like-post, add-to-cart, login)

entities/ # business entities (User, Product, Cart)

shared/ # reusable, neutral code: ui, lib, api, config, etc.

Each layer has clear responsibilities:

shared/– reusable primitives that know nothing about the business (e.g., typography, HTTP client, form helpers).entities/– encapsulate domain models and operations: data structures, domain-specific APIs.features/– implement concrete user interactions built on top of entities.widgets/– compose features and entities into page sections.pages/– wire widgets to routing and data-loading boundaries.processes/– orchestrate multi-step flows and cross-page behaviors.app/– application root, DI providers, top-level configuration.

Unidirectional dependency flow

A core rule in FSD is unidirectional dependencies. In short:

- Higher layers can depend on lower layers, but not vice versa.

- For example,

features/may import fromentities/andshared/, butentities/cannot import fromfeatures/.

That means no circular references like:

entities/user→features/login→entities/user.

By enforcing this rule, FSD keeps the dependency graph clean and prevents architecture from silently degrading as the project grows.

Public API and isolation

Each slice exposes only what other parts of the system are allowed to use through a public API file (often index.ts or public.ts):

src/

features/

add-to-cart/

ui/

AddToCartButton.tsx

model/

addToCart.ts

api/

cartApi.ts

index.ts # public API

index.ts might look like:

// features/add-to-cart/index.ts

export { AddToCartButton } from "./ui/AddToCartButton";

export { useAddToCart } from "./model/addToCart";

Consumers of this feature import only from the public API:

import { AddToCartButton } from "@/features/add-to-cart";

They cannot reach into ./model/addToCart or ./api/cartApi directly. This enforces:

- Encapsulation – internal implementation can change without breaking others.

- Intentional coupling – it becomes clear what is meant to be reused and what is private.

- Safe refactoring – tools can track public API usages easily.

Feature-first organization

Instead of generic components/, FSD organizes around features and entities:

- A “like post” feature lives in

features/like-post/. - All product-related logic lives in

entities/product/. - A recommendation widget lives in

widgets/recommendations/and composes multiple features.

This feature-first approach brings strong cohesion: everything you need to work on a feature is in one place.

Example: structuring a product details page

Imagine an e-commerce Product Details page. In FSD it might look like:

src/

entities/

product/

model/

ui/

features/

add-to-cart/

add-to-wishlist/

rate-product/

widgets/

product-info/

product-recommendations/

pages/

product-details/

ui/

ProductDetailsPage.tsx

index.ts

entities/product– definesProductmodel, queries, and basic UI likeProductPrice.features/add-to-cart– exposes<AddToCartButton />and auseAddToCarthook.widgets/product-info– uses entities and features to compose the central product info block.pages/product-details– collects widgets and wires them to routing params and data fetching.

This structure is easy to navigate and scales naturally as you add more product-related features.

How FSD scales teams and codebases

Feature-Sliced Design is especially helpful when:

- multiple teams work on the same SPA;

- requirements and domains change frequently;

- you expect the app to live for years.

Key advantages:

- Explicit boundaries – layers and slices are clearly separated.

- Predictable imports – developers know exactly where they can import from.

- Gradual adoption – you can introduce FSD slice-by-slice into an existing React/Vue/Angular codebase.

- Tooling support – ESLint rules and code generators can enforce architecture automatically.

Leading architects suggest that while no methodology is universal, FSD provides a pragmatic, battle-tested structure that fits most modern frontend stacks.

Introducing FSD into an existing project: a practical path

You don’t need a big-bang rewrite to adopt FSD. A step-by-step approach works well:

-

Define layers

Decide onapp/,pages/,widgets/,features/,entities/,shared/. Add empty directories and basic lint rules. -

Create first entities and features

Pick one domain (e.g.,User,Product) and move related logic intoentities/. Wrap one user interaction (e.g., login, add-to-cart) into afeatures/slice. -

Expose public APIs

Addindex.tsfiles for the entities and features. Update imports to use those instead of deep internal paths. -

Refactor pages and widgets

Gradually move cross-feature compositions intowidgets/and route-level components intopages/. -

Codify rules

Add lint rules and architectural tests to prevent regressions (for example, disallowentities/importing fromfeatures/).

As demonstrated by projects using FSD, this incremental path keeps the team productive while architecture improves in parallel.

Comparative Analysis: Choosing Your Frontend Architecture

When picking an architecture (or combination), you’re really choosing trade-offs around coupling, cohesion, autonomy, and complexity.

The table below summarizes the main strengths and typical use cases for the five architectures discussed:

| Architecture | Primary Strength | Best Fit |

|---|---|---|

| Layered (MVC/MVP/MVVM) | Clear separation by technical responsibility | Simple–medium apps, small teams, legacy frameworks |

| Component-Based & Atomic Design | Reusable, consistent visual components | Design systems, UI libraries, visually complex apps |

| Micro-Frontends | Independent deployment and team autonomy | Large enterprises, multi-team platforms |

| DDD for Frontend | Strong alignment with business domains | Domain-heavy products with intricate business rules |

| Feature-Sliced Design (FSD) | Feature-first structure with explicit boundaries | Medium–large SPAs, multi-team long-lived products |

Some observations:

- Layered architectures are easy to start with but tend to degrade without additional patterns as complexity grows.

- Component-based architecture is non-negotiable today, but it mainly covers UI composition—not domain complexity.

- Micro-frontends solve organizational scaling; they are heavy-weight if you don’t have that problem.

- DDD gives you language and modeling tools; you still need concrete rules for module layout and dependencies.

- FSD builds on component-based and domain-driven ideas and adds strict layering, public APIs, and import rules tailored for frontends.

Decision checklist for your next project

When deciding on architecture, ask:

-

What is our expected scale?

- Hobby/internal tool → layered + components may be enough.

- Multi-year product → plan for feature/domain-based architecture (DDD, FSD).

-

How many teams will work on the frontend?

- 1–2 teams → FSD inside a single SPA is often sufficient.

- Many teams across departments → micro-frontends plus FSD inside each micro-app.

-

How volatile is our domain?

- Stable, well-known domain → DDD + FSD will pay off quickly.

- Highly exploratory product → start lighter, but keep FSD-compatible boundaries in mind.

-

How much technical debt do we already have?

- Heavy legacy → incremental migration to FSD slices, one feature at a time.

- Greenfield → adopt FSD from day one to avoid entropy.

-

What are our cross-cutting concerns?

- Global design system, authentication, analytics, performance → use

shared/andentities/wisely to centralize these concerns without over-coupling.

- Global design system, authentication, analytics, performance → use

Leading architects increasingly treat Feature-Sliced Design as a flexible meta-architecture that can coexist with others:

- FSD + Atomic Design for design systems;

- FSD + micro-frontends for large organizations;

- FSD + DDD language and modeling patterns for domain-heavy platforms.

Conclusion: Investing in a Structured Future

The frontend is no longer a “thin view layer” on top of a backend. It is a complex, interactive, domain-rich application in its own right. Choosing the right frontend architecture is therefore a strategic decision that shapes your team’s productivity, your ability to onboard new engineers, and your capacity to adapt to changing business goals.

Understanding layered patterns, component-based design, micro-frontends, and domain-driven modeling gives you a strong toolkit. Yet, as applications grow, many teams discover they need more explicit rules about boundaries, dependencies, and feature organization.

This is where Feature-Sliced Design (FSD) stands out. By organizing code by features and entities, enforcing unidirectional dependencies, and exposing stable public APIs, FSD offers a robust methodology for building scalable, maintainable, and predictable frontends. Adopting a structured architecture like FSD is a long-term investment in code quality, team productivity, and sustainable delivery.

Ready to build scalable and maintainable frontend projects?

Dive into the official Feature-Sliced Design Documentation to get started.

Have questions or want to share your experience?

Visit our homepage to learn more!

Disclaimer: The architectural patterns discussed in this article are based on the Feature-Sliced Design methodology. For detailed implementation guides and the latest updates, please refer to the official documentation.