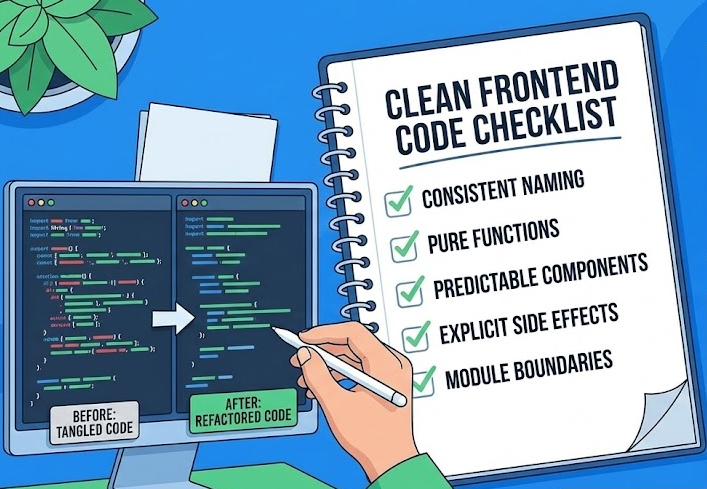

Clean Code in Frontend: A Practical Checklist

TLDR:

A hands-on checklist for clean frontend code: naming, pure functions, predictable components, explicit side effects, and module boundaries. Includes before/after examples, a refactoring workflow, architecture comparisons, and how Feature-Sliced Design keeps large JavaScript/TypeScript apps readable and maintainable.

Clean code in frontend projects is what keeps growth from turning into chaos: it improves code readability, protects code maintainability, and makes refactoring predictable. But UI code evolves fast—components, state, routes, and APIs change every sprint—so “clean” has to be practical, reviewable, and repeatable. Feature-Sliced Design (FSD) on feature-sliced.design provides the missing structure, turning clean code from taste into an architectural habit.

Table of contents

- Why clean code matters in frontend teams

- Clean Code principles translated to JavaScript and TypeScript

- Checklist 1: Clean functions and utilities

- Checklist 2: Clean UI components

- Checklist 3: Clean modules and boundaries

- Refactoring without drama: a safe workflow

- Architecture patterns compared: what they optimize for

- How Feature-Sliced Design supports clean code at scale

- Code review checklist and team practices

- Conclusion

- Disclaimer

Why clean code matters in frontend teams

Clean code is not about aesthetics. It’s about risk management and delivery speed over time.

A key principle in software engineering is that most engineering effort happens after the first release: you spend more time changing existing code than writing brand-new features. That means every confusing component, leaky abstraction, and hidden side effect is a tax you pay repeatedly—during onboarding, code reviews, incident fixes, and feature work.

The business value is measurable

You don’t need an industry report to justify it—you can model it with your own numbers:

- If your team merges 25 PRs/week, and cleaner structure saves 8 minutes per PR in review + follow-ups, that’s 200 minutes/week (~3.3 hours).

- If each new engineer ramps up 5 days faster because the codebase has consistent naming, boundaries, and predictable folders, that’s a full sprint of regained productivity per hire.

- If refactoring a feature becomes a local change instead of a cross-app risk, you reduce regression fixes and shorten lead time.

Clean frontend code also unlocks better collaboration:

- Product work becomes easier to parallelize (clear module ownership).

- QA has fewer “works on my machine” bugs (deterministic state flow).

- Designers and engineers share language through stable UI boundaries (design system + predictable component contracts).

Frontend has special “clean code” failure modes

Compared to many backend codebases, frontend systems tend to accumulate complexity faster because they combine:

- State management (client cache, forms, optimistic updates)

- Concurrency (async effects, race conditions, rendering timing)

- UI composition (components calling components calling hooks)

- Integration surfaces (routing, i18n, analytics, feature flags)

- High churn (product experiments, UI redesigns)

So “clean” isn’t just about small functions—it’s also about coupling, cohesion, modularity, and public API design. Architecture is part of clean code, not a separate concern.

Clean Code principles translated to JavaScript and TypeScript

Robert C. Martin’s Clean Code popularized a simple message: code is read far more than it’s written. In frontend JavaScript/TypeScript, the same idea holds, but the “units” you optimize are often components, hooks, modules, and slices, not just functions.

Leading architects suggest using Clean Code principles as constraints rather than slogans. Below are the practical translations that matter most in modern frontend development.

1) Readability beats cleverness

- Prefer explicit data flow over “smart” abstractions.

- Use TypeScript types to make intent obvious.

- Treat “one-liner wizardry” as a code smell in shared modules.

A good heuristic: if a future teammate can’t explain it in 30 seconds, it’s not clean.

2) Naming is architecture

Clean code naming is not “nice to have.” It defines your domain language and enables scalable refactoring.

Prefer names that reveal:

- Business meaning (e.g.,

invoice,subscription,cartItem) - Role (e.g.,

parse,validate,format,select,map) - Constraints (e.g.,

ActiveUser,PaidPlan,isEligibleForTrial)

Avoid names that hide ambiguity:

data,payload,info,temp,helper,managerhandleThing,doWork,processStuff

3) Functions should do one job, but “job” means outcome

In frontend, a “job” can be:

- compute a derived value (pure)

- map server DTO → UI model

- trigger a single effect (analytics event, navigation)

- coordinate a use case (often belongs to a feature, not a shared util)

If a function both computes values and performs I/O (fetch, storage, navigation), it likely mixes responsibilities and should be split by side-effect boundaries.

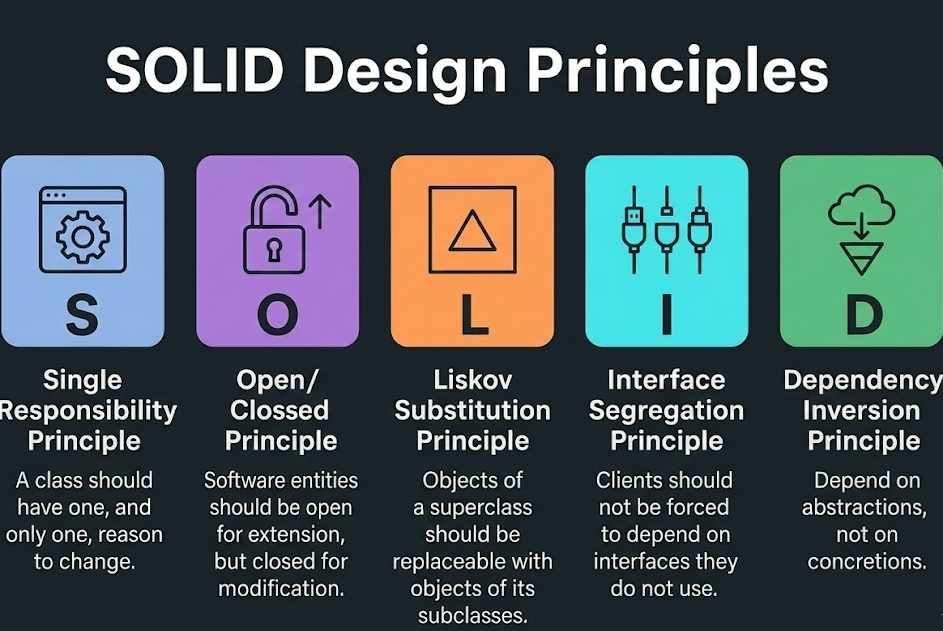

4) SOLID and DRY still apply, but watch the traps

- DRY can create premature abstraction in UI. Duplicating small UI fragments can be cleaner than inventing a generic component with 12 props.

- Single Responsibility Principle maps well to modules/slices: one module should have one reason to change.

- Dependency Inversion is powerful in frontend: depend on stable interfaces (ports) and hide volatile details (adapters).

5) The “Boy Scout Rule” is your refactoring policy

“Leave the campsite cleaner than you found it” works best when paired with small, safe refactors:

- rename a confusing variable

- extract a helper

- move code behind a public API

- delete dead branches

Big-bang rewrites are rarely clean; incremental improvements are.

Checklist 1: Clean functions and utilities

This checklist targets everyday JavaScript/TypeScript code: helpers, mappers, selectors, hooks utilities, formatting, and small business rules.

✅ Naming and intent

- Does the name match the outcome? (

getUserByIdvsfindUserByIdvsrequireUserById) - Is the unit of work clear? (

calculateTotal, nothandleTotal) - Are boolean names unambiguous? (

isPaid,hasAccess,canEdit)

Before (vague):

const process = (data) => {

if (!data) return null;

// ...

};

After (intent):

function normalizeInvoiceDto(dto: InvoiceDto | null): Invoice | null {

if (dto === null) return null;

// ...

}

✅ Parameters and signatures

- Prefer 1–3 parameters; beyond that, use an object parameter.

- Avoid “boolean soup” (

(x, true, false, true)). - Keep default values near the signature, not scattered inside.

Before (hard to call correctly):

function loadUsers(page, size, withInactive, withDeleted, sortKey, sortDir) { /*...*/ }

After (self-documenting):

type LoadUsersParams = {

page: number;

size: number;

includeInactive?: boolean;

includeDeleted?: boolean;

sort?: { key: "name" | "createdAt"; dir: "asc" | "desc" };

};

function loadUsers(params: LoadUsersParams) { /*...*/ }

✅ Purity and side effects

Clean code makes side effects visible.

- Pure functions are easiest to test and refactor.

- If a function has side effects, name it like a command (

saveDraft,trackCheckout,navigateToProfile). - Avoid hidden mutations of inputs.

Before (mutates input silently):

function addDiscount(order, discount) {

order.total = order.total - discount;

return order;

}

After (returns new value):

function applyDiscount(order: Order, discount: Money): Order {

return { ...order, total: order.total - discount };

}

✅ Error handling is part of readability

- Prefer domain-specific errors (

ValidationError,UnauthorizedError). - Return Result-like types for expected failures (validation), throw for unexpected failures (programming errors).

- Never swallow errors with empty

catch.

Pattern (explicit result):

type Result<T> = { ok: true; value: T } | { ok: false; error: string };

function parseMoney(input: string): Result<Money> {

const value = Number(input);

if (Number.isNaN(value)) return { ok: false, error: "Invalid money" };

return { ok: true, value };

}

✅ Complexity and readability guardrails

- Keep branches shallow; extract conditions with expressive names.

- Reduce cyclomatic complexity by moving decision tables into data.

- Prefer

switchon discriminated unions over nestedif.

Before (nested conditions):

function getBadge(user) {

if (user) {

if (user.isAdmin) return "Admin";

if (user.plan) {

if (user.plan === "pro") return "Pro";

if (user.plan === "basic") return "Basic";

}

}

return "Guest";

}

After (flat + explicit):

function getUserBadge(user: User | null): "Admin" | "Pro" | "Basic" | "Guest" {

if (user === null) return "Guest";

if (user.isAdmin) return "Admin";

if (user.plan === "pro") return "Pro";

if (user.plan === "basic") return "Basic";

return "Guest";

}

✅ Utilities: “shared” is a high bar

A common cleanliness trap is dumping everything into utils/.

Ask before creating shared utilities:

- Is it used in multiple domains?

- Is it stable enough to become a shared contract?

- Does it increase coupling between unrelated features?

If the answer is “not yet,” keep it local (feature/entity scope) until it earns promotion.

Checklist 2: Clean UI components

Frontend clean code lives in components. The goal is a component tree that is easy to reason about, easy to test, and easy to change.

✅ Component responsibility and boundaries

A clean component usually fits one of these roles:

- Presentational: renders UI from props; minimal state.

- Container: orchestrates data fetching/state; composes presentational components.

- Page-level composition: connects routing, layouts, widgets.

- Feature UI: implements a user action (submit, filter, checkout).

If your component does all of these, it’s a refactoring candidate.

Smell: “God component” with:

- many hooks (

useEffectx 5,useMemox 7) - mixed concerns (fetching + formatting + UI)

- ad-hoc state machine logic in JSX

✅ Props: contracts, not dumping grounds

- Prefer fewer props with strong types.

- Use domain types (

Invoice,CartItem) instead of raw DTOs. - Avoid passing callbacks that depend on hidden external state.

Before (wide, leaky props):

<UserCard

user={userDto}

locale={locale}

theme={theme}

onClick={() => navigate(`/users/${userDto.id}`)}

onTrack={(e) => analytics.track(e)}

featureFlags={flags}

/>

After (narrow contract + stable dependencies):

type UserCardProps = {

user: User;

onOpenProfile: (id: UserId) => void;

};

<UserCard user={user} onOpenProfile={openUserProfile} />

✅ State ownership: keep it close to where it changes

- UI state (tabs, local filters) belongs near the UI.

- Business state (cart, auth, permissions) belongs in feature/entity model layers.

- Avoid prop drilling by moving state up only when multiple siblings truly share it.

A practical rule: state should live at the lowest common ancestor of all consumers and all mutators.

✅ Effects: design them like a public API

Effects are where clean code often breaks.

- Each

useEffectshould have one purpose. - Dependencies should be correct; don’t “disable the lint rule” to make it quiet.

- Encapsulate complex async flows in a hook or feature action.

Before (effect does everything):

useEffect(() => {

setLoading(true);

fetch(`/api/users/${id}`)

.then((r) => r.json())

.then((dto) => {

setUser(dto);

analytics.track("user_loaded", { id: dto.id });

})

.catch(() => setError(true))

.finally(() => setLoading(false));

}, [id]);

After (separate concerns, explicit actions):

const { user, status, error } = useUserQuery(id);

useEffect(() => {

if (status === "success") trackUserLoaded(id);

}, [status, id]);

✅ Rendering logic: keep JSX boring

Clean JSX is predictable:

- Avoid inline anonymous functions in hot paths unless necessary.

- Extract non-trivial conditions into variables (

const canCheckout = ...). - Extract complex layout chunks into subcomponents.

Before (logic noise):

return (

<div>

{items.length > 0 ? (

items.map((x) => (

<Row key={x.id} onClick={() => onSelect(x.id)}>

{x.name} {x.price > 0 ? `$${x.price}` : "Free"}

</Row>

))

) : (

<Empty />

)}

</div>

);

After (clear intent):

const hasItems = items.length > 0;

if (!hasItems) return <Empty />;

return (

<div>

{items.map((item) => (

<ItemRow key={item.id} item={item} onSelect={onSelect} />

))}

</div>

);

✅ Accessibility and semantics are part of clean code

“Clean UI” includes correct semantics:

- use real buttons for actions

- label inputs properly

- keep focus management predictable

- avoid div-clickable anti-patterns

This improves maintainability too: fewer special cases and less CSS/JS glue.

✅ Testing strategy for components

A clean test suite matches responsibilities:

- Unit tests for pure functions and mappers.

- Component tests for critical UI logic (render + interactions).

- Integration tests for feature flows (routing, async, state).

If a component is hard to test, it often means responsibilities are mixed or dependencies are not isolated.

Checklist 3: Clean modules and boundaries

In large frontend codebases, cleanliness depends on module boundaries more than local style.

✅ Coupling and cohesion

- High cohesion: a module’s files work toward one purpose.

- Low coupling: modules interact through narrow, stable contracts.

Clean code feels “local”: when you change a feature, you mostly stay inside that feature. If a small change requires touching five unrelated folders, your coupling is too high.

✅ Public API first

Every non-trivial module should have a public API that answers:

- What do consumers need?

- What is internal?

- What is stable vs volatile?

A practical pattern in TypeScript is a single entry point:

// feature/auth/index.ts

export { AuthProvider } from "./ui/AuthProvider";

export { useSession } from "./model/useSession";

export { signIn, signOut } from "./model/authActions";

Consumers import from feature/auth instead of deep paths. This supports refactoring because internals can move without rewriting imports.

✅ Dependency direction and layering

A dependency graph should flow in one direction, like a set of concentric rings:

- Stable, generic layers at the bottom (shared tooling, primitives)

- Domain concepts above (entities)

- User actions above that (features)

- Composition at the top (widgets/pages/app)

If a “lower” layer imports from a “higher” layer, you create a cycle that makes changes risky.

✅ Avoid cross-cutting “god services”

Frontend god services are often:

api.tsthat knows every endpoint and transformationstore.tsthat holds everythinghelpers.tsused by half the app

Prefer slicing by domain or feature, and hide volatile integration details behind stable interfaces.

✅ Keep data models explicit

A common maintainability issue is passing raw server DTOs through UI.

Cleaner approach:

- Define DTO types near API layer.

- Map to domain/UI models near the boundary.

- Keep UI components on domain models.

This reduces “stringly-typed” code and clarifies intent.

Refactoring without drama: a safe workflow

Clean code is sustainable only if refactoring is normal, not terrifying.

As demonstrated by projects using FSD, the most reliable refactoring happens when you combine small steps with clear boundaries.

A practical, repeatable refactoring loop

- Protect behavior

- Add or update a test (unit/component/integration).

- Or create a quick “contract check” (e.g., snapshot of mapper output).

- Make structure changes

- rename for clarity

- extract functions/components

- move code behind a public API

- Reduce coupling

- replace deep imports with entry-point imports

- introduce adapters at boundaries (API, storage, routing)

- Delete

- remove dead branches, unused exports, obsolete flags

- Follow up

- add a lint rule, codemod, or review checklist item to prevent regressions

What to avoid

- “Refactor while adding feature” without a safety net

- Large folder moves without stable public APIs

- Unreviewed architecture changes in the same PR as product changes

Clean code grows fastest when refactoring is treated as a standard part of delivery, not a special event.

Architecture patterns compared: what they optimize for

Clean code scales best when architecture supports it. Different methodologies optimize for different things, and understanding the trade-offs helps you choose intentionally.

Common patterns and their frontend implications

| Approach | What it's good at | Where clean code often breaks in large frontends |

|---|---|---|

| MVC / MVP / MVVM | Clear separation of view and logic; familiar mental model | Tends to become framework-specific; boundaries blur as features grow; “model” becomes a catch-all |

| Atomic Design | Strong UI composition vocabulary; good for design systems | Great for UI reuse, but weak guidance for business logic and feature boundaries; can encourage “component-first” over “domain-first” |

| Domain-Driven Design + Clean/Hexagonal | Strong domain modeling; explicit boundaries and dependency rules | Requires discipline and adaptation for UI; teams can over-engineer layers; needs a concrete folder strategy |

| Feature-Sliced Design (FSD) | Practical boundaries for product features; predictable structure; scalable modularity | Requires learning the slicing mindset; needs consistent public APIs and import discipline |

Key takeaway

Clean code practices (naming, small units, tests) matter everywhere. But architecture determines whether those practices stay clean under growth.

If your structure encourages “just import it from anywhere,” clean code decays into spaghetti even with great formatting.

How Feature-Sliced Design supports clean code at scale

Feature-Sliced Design (FSD) is an architectural methodology built specifically for frontend complexity: many features, many contributors, constant change.

Its core promise is simple: make boundaries obvious so clean code stays clean when the codebase grows.

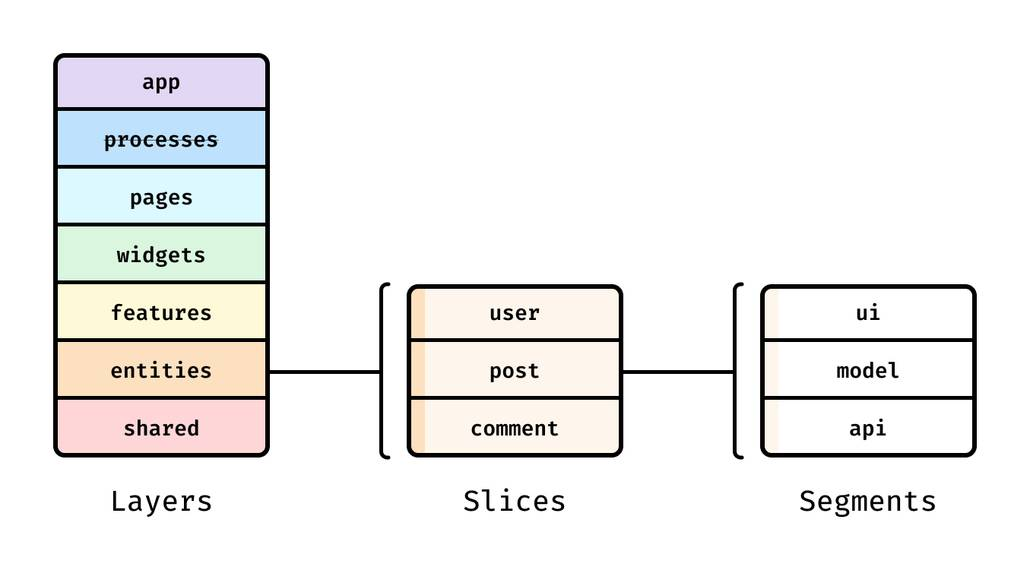

The FSD mental model: layers → slices → segments

- Layers define responsibility levels (from composition to reusable primitives).

- Slices group code by domain/feature (high cohesion).

- Segments separate technical aspects inside a slice (

ui,model,api, etc.).

A typical layer set:

app— app-wide setup (providers, routing, initialization)pages— route-level compositionwidgets— reusable page blocks (composition of features/entities)features— user actions and use cases (login, checkout, filters)entities— business entities (user, cart, invoice)shared— generic UI kit, libs, config, utilities

This is clean code applied to structure: everything has a place.

Directory structure example (tangible and scalable)

src/

app/

providers/

routing/

pages/

checkout/

profile/

widgets/

header/

cartSummary/

features/

addToCart/

signIn/

applyPromoCode/

entities/

cart/

model/

ui/

api/

index.ts

user/

model/

ui/

api/

index.ts

shared/

ui/

lib/

api/

config/

Notice how features (actions) differ from entities (domain objects). This distinction is a practical way to reduce coupling: UI components don’t need to know the entire app; they talk to the relevant slice APIs.

The clean code advantage: predictable dependency direction

You can describe FSD as a dependency diagram:

- Imports flow down from

app → pages → widgets → features → entities → shared. - Shared code never imports from features/pages.

- Features can depend on entities and shared primitives.

- Pages compose widgets/features but avoid implementing business logic directly.

This encourages:

- Isolation: features are easier to move, test, and refactor.

- Stable public APIs: slices expose what’s needed, hide internals.

- Lower cognitive load: you can “guess” where code lives.

Turning “clean code” into a team checklist with FSD

Clean code guidelines are easiest to enforce when structure supports them. In FSD, many rules become mechanical:

-

Where should this code go?

If it’s a user action →features. If it’s domain state/logic →entities. If it’s generic UI →shared/ui. -

Who is allowed to import this?

If it’s internal to a slice, it stays unexported. If it’s meant for reuse, expose it viaindex.ts. -

How do we avoid “utils dumping”?

Keep helpers local to a slice until they are truly cross-domain. -

How do we reduce refactor risk?

Consumers import from slice public APIs, so internals can move freely.

Example: refactoring a messy “checkout” component using FSD thinking

Before: page owns everything (hard to refactor):

- API calls in the page

- form rules in the component

- cart calculations in UI

- analytics calls mixed with rendering

After: responsibilities split into slices:

entities/cartowns cart state and derived selectorsfeatures/applyPromoCodeowns promo flow + validationfeatures/checkoutowns submit use casepages/checkoutcomposes widgets/features and keeps routing concerns

This produces cleaner code because each unit has a single reason to change.

Practical guidance: introduce FSD without rewriting everything

You can adopt FSD incrementally:

- Start by establishing the layer folders and import rules.

- Move one high-churn flow into

features/(e.g., sign-in). - Extract one entity model (e.g.,

entities/userwith types + selectors). - Create slice public APIs and reduce deep imports.

- Repeat per feature, using refactoring PRs as opportunities.

A structured architecture like FSD is not a ceremony. It’s a pragmatic way to make clean code the default outcome of everyday work.

For deeper patterns, naming rules, and import conventions, the official documentation on feature-sliced.design provides a solid next step.

Code review checklist and team practices

Clean code improves fastest when your workflow reinforces it. The goal is to make the “right” path easy: consistent linting, consistent structure, and a review checklist that focuses on maintainability.

A practical code review checklist (use in PR templates)

| Area | What to check | Why it matters |

|---|---|---|

| Readability | Names reveal intent; JSX is boring; no clever one-liners | Reviewers spend less time decoding and more time validating behavior |

| Boundaries | Code lives in the right layer/slice; no deep imports bypassing public API | Prevents hidden coupling and keeps refactors local |

| Side effects | Effects are explicit; async flows isolated; error handling is clear | Reduces flaky behavior and makes bugs easier to fix |

Team practices that keep code clean

- Automate style: formatting and linting should be non-negotiable (Prettier + ESLint + TypeScript strictness where possible).

- Adopt import boundaries: use tooling to prevent forbidden imports (especially important in FSD).

- Measure what matters: track build times, flaky tests, and review cycle time. Cleaner code typically improves these.

- Document conventions: a short “how we structure code” page beats tribal knowledge.

- Make refactoring normal: small refactors are welcome; large rewrites need a plan and safety net.

Clean code is a team sport. Architecture makes it scalable; process makes it sustainable.

Conclusion

Clean code in frontend is a practical discipline: clear naming, small focused units, explicit side effects, and strong module boundaries lead to readable, maintainable code that refactors smoothly. The checklists above help you write cleaner functions, components, and modules—and they also improve code reviews by giving teams shared criteria beyond “looks good to me.” Most importantly, clean code becomes durable when architecture supports it: Feature-Sliced Design creates predictable boundaries, stable public APIs, and a dependency direction that keeps complexity under control as the product grows.

Ready to build scalable and maintainable frontend projects? Dive into the official Feature-Sliced Design Documentation to get started.

Have questions or want to share your experience? Visit our homepage to learn more!

Disclaimer

Disclaimer: The architectural patterns discussed in this article are based on the Feature-Sliced Design methodology. For detailed implementation guides and the latest updates, please refer to the official documentation.