Layered Architecture: Still Relevant for Frontend?

TLDR:

Is layered architecture outdated in the age of React and micro-frontends? This deep-dive maps classic presentation/business/data-access layers to modern frontend concerns (UI, state, API), shows how to enforce boundaries, and explains why Feature-Sliced Design combines layering with feature locality for scalable teams.

Layered architecture is still one of the clearest ways to tame frontend complexity: separate the presentation layer, business layer, and data access layer so change stays local instead of turning into spaghetti. But in today’s React/Vue/Angular apps—where state management, API orchestration, and domain rules often leak into UI—teams increasingly look to Feature-Sliced Design (FSD) on feature-sliced.design to keep the benefits of layering without losing feature discoverability.

Table of contents

• What layered architecture means in frontend

• Mapping classic n-tier layers to modern frontend

• Layering in React, Vue, and Angular

• Enforcing boundaries between layers

• Where layered architecture struggles on the frontend

• Layered vs feature-based and other patterns

• How Feature-Sliced Design evolves layering

• Migration path: from ad-hoc to FSD

• Measuring results: maintainability and delivery speed

• FAQ

• Conclusion

What layered architecture means in frontend

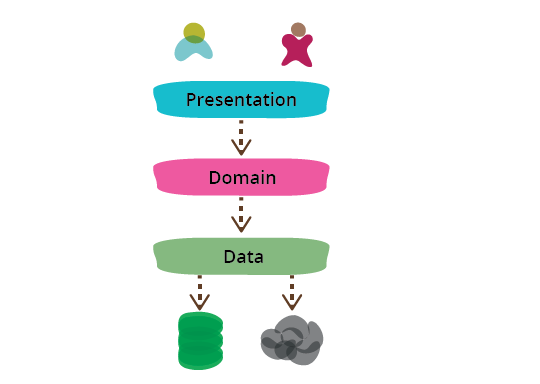

Layered architecture (also called tiered architecture, multi-layer architecture, or stratified architecture) is a structural pattern where code is grouped by responsibility into layers with a clear dependency direction. In classic n-tier architecture, the layers are often described as:

• Presentation (UI and interaction)

• Business (rules and workflows)

• Data access (persistence and I/O)

In frontend work, the names may shift—UI layer, domain layer, application layer, service layer, infrastructure layer—but the design goal stays the same: reduce coupling, increase cohesion, and protect the most stable logic from the most volatile details.

The promise: cheaper change through separation of concerns

A key principle in software engineering is that a system is easier to evolve when:

• Responsibilities are isolated (high cohesion)

• Dependencies are controlled (low coupling)

• Public APIs are explicit (encapsulation)

• Policy is separated from mechanism (rules vs implementation)

Layering operationalizes these principles. Instead of scattering business decisions across components, hooks, stores, and API calls, you centralize decisions in a predictable place and keep the UI mostly declarative.

When layering works, you tend to see:

• Faster refactors because “what changes” is localized

• Easier testing because rules are not tied to rendering

• Fewer dependency cycles and less “import archaeology”

Frontend is no longer “just presentation”

Modern frontends routinely include:

• Application workflows (wizards, drafts, multi-step checkout)

• Complex state transitions (optimistic updates, offline mode, retries)

• Domain rules (permissions, validation, pricing, quotas, feature flags)

• A real integration surface (REST/GraphQL, websockets, analytics SDKs, browser storage, SSR)

If you treat all of that as “presentation,” components become controllers, stores become god objects, and I/O creeps into view code.

Layering is not “folders,” it’s dependency discipline

A layered folder structure is easy to create:

src/ components/ services/ api/

But it only becomes architecture when you can answer, consistently:

• Can UI call the API client directly, or must it go through a use case/facade?

• Can the domain import a React hook, or is it framework-agnostic?

• Where do DTOs stop and domain models start?

• What is public vs private inside a module?

If boundaries aren’t enforced, the “layered architecture” label becomes cosmetic.

Mapping classic n-tier layers to modern frontend

To apply layering to frontend, don’t copy backend diagrams blindly. Translate tiers into frontend realities and keep the rules simple.

A practical mapping that works in SPAs and SSR apps

Presentation layer (UI layer)

• Pages, widgets, components, routing, layout

• Local UI state (forms, toggles, focus)

Goal: Render state and capture user intent.

Business layer (application + domain logic)

• Use cases (commands): “Place order”, “Sign in”, “Apply coupon”

• Policies and invariants: validation, pricing rules, permissions

• Orchestration: retries, optimistic updates, multi-step flows

Goal: Turn intent into decisions and coordinate work.

Data access layer (infrastructure layer)

• API client, repositories, adapters, caching

• Auth headers, refresh tokens, rate limiting

• Storage (IndexedDB/LocalStorage), telemetry, feature flags

Goal: Perform I/O and translate external formats into internal ones.

A common refinement is to split the business layer into:

• Domain: pure rules and models (stable)

• Application: workflows and coordination (changes with product flows)

The dependency rule that pays for itself

A simple dependency direction:

• Presentation → Application/Domain

• Application → Domain

• Infrastructure → Domain (for mapping)

• Application depends on interfaces; Infrastructure implements them

This keeps UI unaware of endpoints, keeps domain logic free of frameworks, and keeps integrations replaceable.

Diagram: the “front-end n-tier” command flow

[UI event] ↓ [Use case / Facade] ↓ (via port / interface) [Repository / Adapter] ↓ [HTTP / Storage / SDK] ↑ [Result] → state update → render

Pseudo-code example: use case + repository port

// domain/policies/canApplyDiscount.ts

export function canApplyDiscount(role: 'user' | 'admin', percent: number) {

return role === 'admin' || percent <= 30

}

// application/ports/OrdersRepo.ts

export type OrdersRepo = {

saveDraft(draft): Promise<{ id: string }>

place(id: string): Promise<{ id: string }>

}

// application/useCases/placeOrder.ts

export async function placeOrder(deps: { repo: OrdersRepo; role }, input) {

if (!canApplyDiscount(deps.role, input.discountPercent)) {

return { ok: false, error: 'DiscountNotAllowed' }

}

const draft = await deps.repo.saveDraft(input)

const order = await deps.repo.place(draft.id)

return { ok: true, orderId: order.id }

}

// infrastructure/http/ordersRepoHttp.ts

export function ordersRepoHttp(apiClient): OrdersRepo {

return {

saveDraft: (draft) => apiClient.post('/orders/draft', draft),

place: (id) => apiClient.post(`/orders/${id}/place`),

}

}

The benefit is immediate: the use case is testable with a fake repo, and the UI never sees endpoints or DTO quirks.

Layering in React, Vue, and Angular

Layering is framework-agnostic, but frameworks shape how easy it is to maintain boundaries.

A technology-agnostic layered structure

src/ presentation/ pages/ components/ routing/ application/ useCases/ facades/ state/ ports/ domain/ entities/ policies/ valueObjects/ infrastructure/ http/ repositories/ storage/ telemetry/

This supports classic layered design and creates clear seams for refactoring.

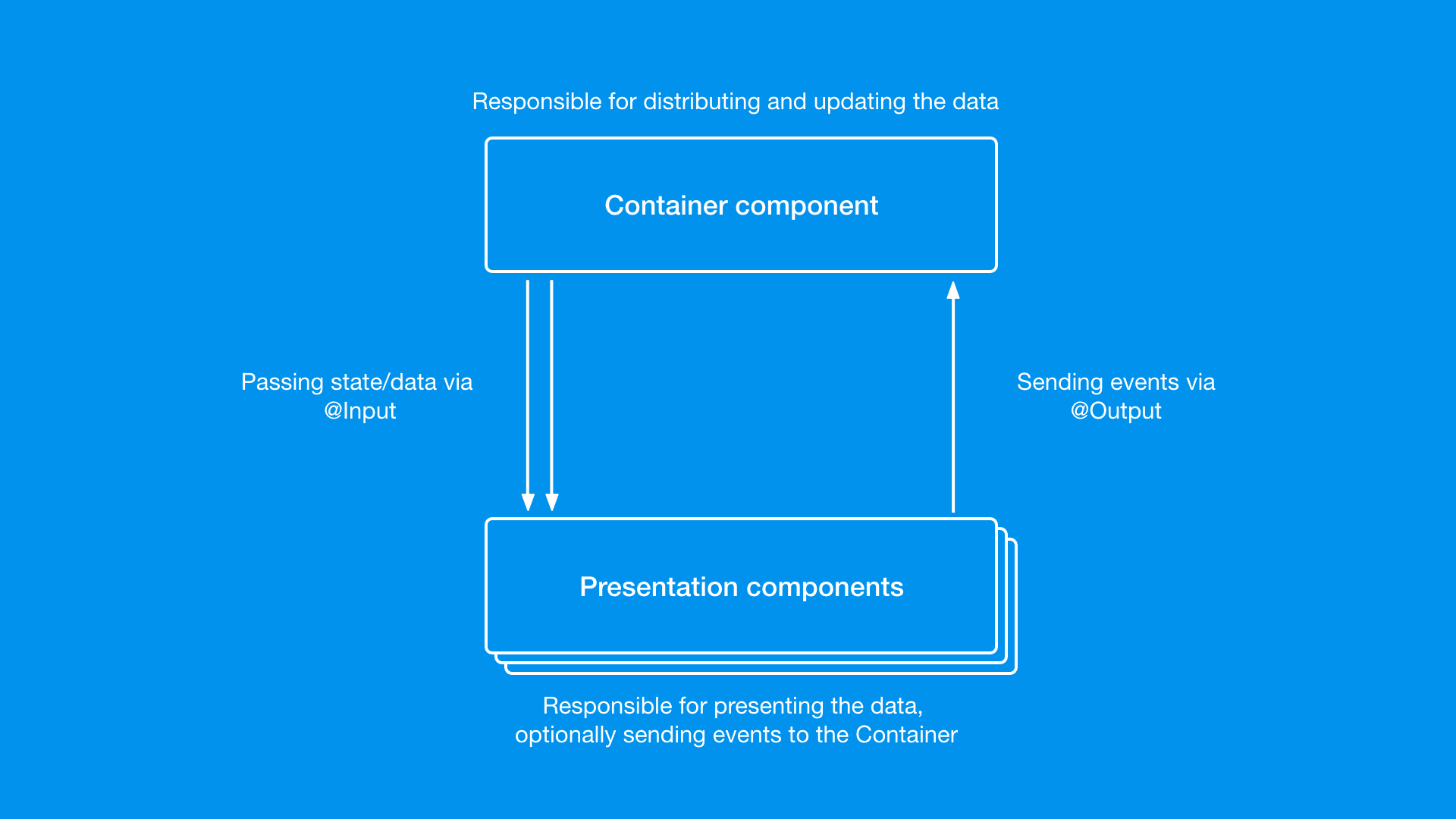

React and Vue: layering requires explicit choices

React and Vue don’t force structure, so teams often drift into:

• “Hook soup”: business rules hidden in a web of useX() helpers

• “Component controllers”: JSX files that fetch, validate, mutate, and navigate

• “God store”: a single state container that owns all policies

To keep layered architecture healthy:

- Components stay presentation-first (render + dispatch intent).

- Workflows live in application (use cases, facades, state machines).

- Stable rules live in domain (policy functions, value objects).

- All I/O lives in infrastructure (repositories, API client, adapters).

A practical UI integration pattern:

• UI calls a facade: checkoutFacade.placeOrder(form)

• facade calls one or more use cases

• use cases call repository ports

• infrastructure adapters perform HTTP and mapping

This keeps rendering fast to change while protecting core behavior.

Angular: why it naturally nudges you toward layers

Angular encourages layering because:

• Components are clearly presentation units.

• Services are the default home for orchestration and data access.

• DI supports programming to abstractions.

• Interceptors form a strong infrastructure boundary (auth, retries, logging).

A pragmatic mapping:

• Presentation: components + templates + pipes

• Business/application: facades (wrap NgRx/signals), orchestration services

• Data access: repositories using HttpClient, plus mappers for DTO → domain

• Domain: policy functions and models (kept free of Angular imports)

If you’ve ever refactored a “smart component” into a “thin component + service,” you were applying layered architecture principles.

Where state management fits

Treat state transitions as part of the business layer:

• UI reads state and emits intent

• application/model owns transitions and coordination

• infrastructure owns side effects (HTTP, storage, analytics)

The specific state library matters less than keeping boundaries consistent.

Enforcing boundaries between layers

The hardest part of layered architecture isn’t drawing layers—it’s keeping them intact as deadlines hit.

Step 1: Write a small “architecture contract”

Keep it short and enforceable. Example rules:

• Domain cannot import from UI, application, or infrastructure

• Application cannot import from UI

• UI cannot import infrastructure adapters directly

• Infrastructure cannot import UI

If rules don’t fit on half a page, they won’t be followed.

Step 2: Design explicit public APIs

A public API is the approved entry point for a module/slice. Instead of deep imports, expose stable surfaces:

• @/domain/order

• @/features/applyCoupon

This improves encapsulation and makes refactors safer.

These constraints also align with SOLID design principles—especially the Dependency Inversion Principle (DIP): stable policies depend on abstractions, and volatile details (HTTP, storage, framework glue) implement them.

Step 3: Make layer transitions visible in imports

Use TypeScript path aliases:

• @/domain/...

• @/application/...

• @/infrastructure/...

• @/presentation/...

Relative imports can hide boundary crossings; explicit paths make them obvious.

Step 4: Automate checks (lint + CI)

Manual enforcement doesn’t scale. Practical options include:

• ESLint restricted import rules

• “no deep imports” rules (force public APIs)

• Dependency graph checks for cycles/forbidden edges

A simple workflow:

- Editor shows a lint error on forbidden import.

- Developer routes through the correct public API or moves code to the right layer.

- CI prevents architectural drift from landing in main.

Step 5: Align tests with layers

Layering improves testing when tests match responsibilities:

• Domain tests: pure functions and policies

• Application tests: use cases with fake repositories

• Infrastructure tests: adapters and mapping (contract tests)

• UI tests: behavior and composition

This increases confidence while keeping tests maintainable.

Where layered architecture struggles on the frontend

Layered architecture has real trade-offs, especially when applied as pure horizontal tiers.

1) Discoverability: features are scattered across layers

A single product change may touch multiple directories across tiers. That’s not always wrong, but it can feel like “hunting” when the app grows and multiple teams are involved.

2) “Shared” becomes an escape hatch

Without feature ownership, teams create shared/utils and slowly move business logic there because it’s convenient. Over time, shared becomes a tight coupling hub.

3) The business layer becomes a mega-service

Layering separates UI from logic, but it doesn’t automatically define business modules. Without an additional modularity concept, orchestration services can become large and ambiguous.

4) Product work is feature-driven

Teams think in user journeys: “search,” “checkout,” “profile.” Pure technical tiers can work against how developers navigate and own changes.

These issues are why modern frontend architecture often combines layering with vertical slicing.

Layered vs feature-based and other patterns

Frontend teams rarely choose one pattern. Most codebases blend ideas like MVC naming, Atomic Design components, and DDD-inspired models.

Comparison table: popular structural approaches

| Approach | How it structures code | Best fit when… |

|---|---|---|

| MVC / MVP | Screen-driven units (view + controller/presenter + model) | You want a clear UI flow model; often framework-specific |

| Atomic Design | UI grouped by granularity (atoms → organisms → templates) | You are building a design system/component library |

| Layered / n-tier | Horizontal tiers (presentation/business/data access) | You need strong UI–logic–I/O separation and testable rules |

| DDD-inspired modules | Code aligned to domain language and bounded contexts | The domain is complex and ownership matters |

| Feature-Sliced Design | Layered composition + feature slices + segments | You need boundary discipline and feature locality at scale |

The key insight: layers and features are not opposites.

• Layers protect responsibilities and dependency direction.

• Features optimize discoverability and locality of change.

A practical hybrid is: vertical slices with internal layering—and that hybrid is what FSD formalizes.

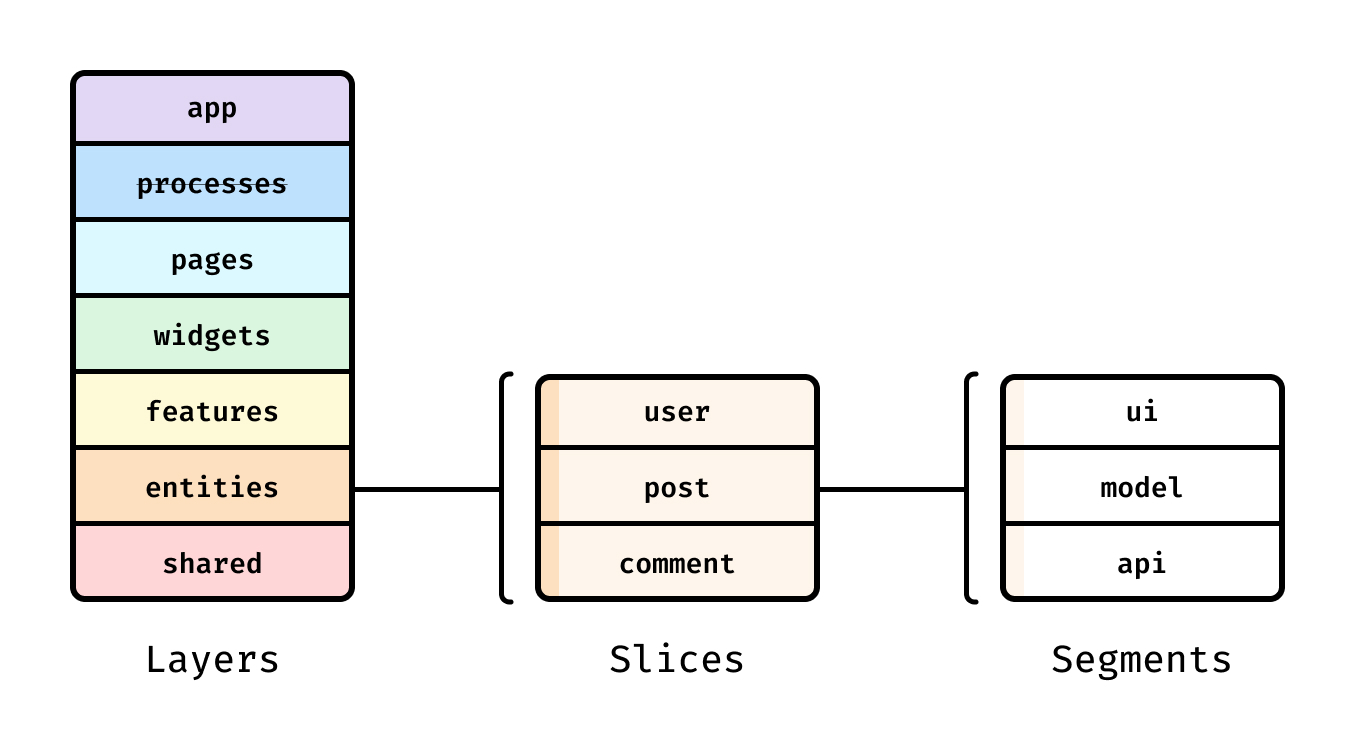

How Feature-Sliced Design evolves layering

Feature-Sliced Design (FSD) is a community-driven methodology tailored for frontend scale. It keeps layered architecture relevant by combining a layered dependency gradient with feature-first modularity.

FSD layers: a dependency gradient that stays intuitive

In FSD, layers represent the app composition stack:

• shared: reusable primitives (UI kit, utilities, base API)

• entities: domain nouns (User, Order, Product)

• features: user actions (Sign in, Apply coupon, Add to cart)

• widgets: meaningful UI blocks (Header, Checkout summary)

• pages: route-level assembly

• processes: cross-page flows (onboarding, checkout)

• app: initialization and global providers

Rule of thumb: higher layers may import from lower layers; lower layers should not import from higher ones. This is layered architecture thinking, phrased in a way that matches frontend development.

Slices and segments: vertical slicing + mini n-tier

Within a slice, segments usually look like:

• ui (presentation)

• model (business/application logic, state)

• api (data access)

• lib / config (helpers, constants local to the slice)

This creates a “mini n-tier architecture” per feature:

• feature rules stay close to feature code

• UI stays composable

• API integration stays encapsulated

• cross-feature coupling becomes reviewable

As demonstrated by projects using FSD, this combination reduces the “shared dumping ground” effect while keeping dependency discipline.

Example: checkout with clear ownership

src/ pages/ checkout/ widgets/ checkoutSummary/ features/ applyCoupon/ ui/ model/ api/ placeOrder/ ui/ model/ api/ entities/ order/ model/ api/ shared/ ui/ api/ lib/

If your team has ever asked “where should this go?”, FSD answers with a consistent, scalable vocabulary.

Migration path: from ad-hoc to FSD

You can adopt FSD incrementally. The goal is not rearranging files—it’s shifting responsibilities and enforcing boundaries.

Step 1: Create a disciplined Shared layer

• Move truly generic UI to shared/ui.

• Create shared/api for the base API client and cross-cutting concerns.

• Keep shared/lib small; reject anything with business meaning.

Step 2: Extract Entities (your domain nouns)

• Create entities/* modules for stable domain concepts.

• Move types, derived calculations, and domain helpers there.

• Add DTO → domain mapping close to the entity.

Step 3: Carve Features around user intent

Pick a high-impact action and move it as a slice:

• UI → features/<name>/ui

• state/orchestration → features/<name>/model

• I/O integration → features/<name>/api

Move the whole slice, then delete the old glue.

Step 4: Add enforcement to prevent regression

• Introduce path aliases aligned with layers.

• Add lint rules for illegal imports and deep imports.

• Prefer public APIs to internal paths.

Incremental migration works best when your constraints are “always on.”

Measuring results: maintainability and delivery speed

Architecture should improve outcomes you can feel. You don’t need perfect analytics—just consistent indicators.

A practical metrics table (with useful targets)

| Indicator | How to measure | Healthy target (guideline) |

|---|---|---|

| Change locality | Count slices/layers touched per feature request | 1–4 slices for most changes |

| Dependency health | Cycles + forbidden edges in the dependency graph | 0 cycles; violations trend to 0 |

| Onboarding friction | Time for a new dev to locate + change a feature safely | Days, not weeks |

These are not universal truths; they are useful targets that help teams talk about architecture objectively.

Quick qualitative checks

• Do PRs have fewer “where does this belong?” comments?

• Does moving a feature’s internal file require fewer import fixes (thanks to public APIs)?

• Does shared stay small and intentional?

• Are regressions from refactors becoming rarer?

When the answer becomes “yes” more often, your architecture is doing its job.

FAQ

Is layered architecture overkill for frontend?

It can be for small, short-lived apps. But for products with frequent change, multiple contributors, and long maintenance horizons, layering is a positive constraint. Start lightweight (UI vs business vs I/O separation), then grow into FSD when discoverability and ownership become the real bottlenecks.

Where do “services” belong?

“Service” is overloaded. In a layered approach:

• orchestration services belong to the application/business layer

• HTTP and storage services belong to infrastructure/data access

• pure policy functions belong to the domain layer

Naming by intent (useCase, repo, policy, adapter, facade) reduces ambiguity.

Can I mix FSD with Clean Architecture or DDD?

Yes. FSD gives you a scalable project structure and boundary rules; DDD gives you language and domain ownership; Clean Architecture strengthens dependency inversion (ports/adapters). Many teams model nouns in entities and keep use cases in features/*/model while using adapters in shared/api or features/*/api.

How do I stop deep imports in practice?

• Provide a public API per slice (index exports).

• Add a lint rule that forbids importing internal paths.

• Treat deep imports as a review smell: if it bypasses the public API, it usually bypasses encapsulation.

What about shared UI libraries and design systems?

They fit naturally in shared/ui (or as a separate package in a monorepo). Atomic Design can live inside the design system package, while FSD/layering organizes the application that consumes it.

Conclusion

Layered architecture remains relevant for frontend because it protects the code that changes least (domain rules and workflows) from the details that change most (UI and integrations). The practical win isn’t the folder tree—it’s the dependency direction: UI depends on use cases, use cases depend on domain policies, and infrastructure adapters handle I/O behind stable ports. When teams skip enforcement, layering collapses into shortcuts (UI calling endpoints, DTOs leaking everywhere, “shared” becoming a junk drawer).

The most resilient frontend codebases combine layering with feature locality. Based on our experience with large-scale projects, this is where Feature-Sliced Design fits: FSD keeps a layered gradient across the app while letting each feature slice own its own mini presentation/model/data-access structure. The result is clearer ownership, safer refactors, faster onboarding, and a more predictable path for growth—an investment that pays back every sprint.

Ready to build scalable and maintainable frontend projects? Dive into the official Feature-Sliced Design Documentation to get started.

Have questions or want to share your experience? Visit our homepage to learn more!

Disclaimer: The architectural patterns discussed in this article are based on the Feature-Sliced Design methodology. For detailed implementation guides and the latest updates, please refer to the official documentation.