Is Your Code Readable? 7 Rules to Follow

TLDR:

Readable code reduces cognitive load, speeds up code reviews, and makes refactoring safer—especially in large frontend projects. This guide shares 7 actionable rules to improve code readability, from intent-driven naming and explicit data flow to automated formatting, meaningful comments, clear public APIs, and a feature-first structure powered by Feature-Sliced Design.

Code readability is the difference between a codebase that welcomes change and one that fights every commit. When naming conventions drift, self-documenting code turns into guesswork, and code comments explain the obvious instead of intent, even experienced teams lose flow. Feature-Sliced Design (FSD) on feature-sliced.design helps make readability systematic by enforcing clear boundaries, public APIs, and a predictable structure that scales.

A quick code readability checklist you can apply in code review

Before you refactor anything, you can audit readability with a few fast, repeatable checks. A key principle in software engineering is that what you can’t quickly understand, you can’t safely change—so treat readability as a first-class acceptance criterion.

Use this checklist in pull requests, architecture reviews, and onboarding sessions:

• Intent in 10 seconds: Can someone unfamiliar with the code explain what the module does after a quick scan?

• Single responsibility: Does each function/component have one clear job (high cohesion)?

• Shallow nesting: Are there more than ~2 levels of indentation in critical paths?

• Explicit inputs/outputs: Are dependencies passed via arguments/props instead of hidden globals?

• Predictable structure: Can you guess where related files live based on conventions?

• Stable boundaries: Is there a clear public API, or are consumers importing internals?

• Consistent style: Are formatting, linting, and TypeScript rules enforced automatically?

• Comments explain “why”: Do comments capture constraints, trade-offs, or domain rules?

• No “junk drawers”: Are utils/, helpers/, common/ turning into dumping grounds?

• Low coupling across domains: Do changes in one feature regularly break another?

A compact way to compare “good signals” and “red flags”:

| Review check | Good signal | Red flag |

|---|---|---|

| Naming | Domain terms, consistent verbs, boolean prefixes | Abbreviations, overloaded names, “temp” variables |

| Structure | Feature/domain grouping, clear entry points | “components” mega-folders, deep relative imports |

| API boundaries | Imports from module index/public API | Imports from deep paths into internals |

| Control flow | Guard clauses, linear “happy path” | Nested conditionals, mixed concerns, hidden side effects |

| Comments | “Why/constraints/edge cases” | Restating code, stale explanations |

If your project fails multiple checks above, you don’t just have a style issue—you likely have architecture-level readability debt (high coupling, inconsistent modularity, unclear boundaries).

Why code readability is the most cost-effective quality metric

“Readable code” isn’t aesthetic. It’s economic.

A practical model many teams recognize is:

Time to deliver change = time to understand + time to modify + time to verify

Improving readability reduces the first term dramatically, and it also reduces defects (verification becomes simpler because behavior is easier to reason about).

Readability is really about cognitive load

In modern frontend systems—React/Vue/Angular apps with routing, state management, API layers, design systems, and feature flags—the largest tax is context switching. Your brain pays for:

• tracking data flow across files

• remembering conventions that aren’t written down

• interpreting ambiguous names

• inferring hidden side effects (network calls, global state mutations, event listeners)

• re-learning “how this project does things” after time away

Readable code reduces cognitive complexity by making intent visible through:

• high cohesion (related logic lives together)

• low coupling (boundaries prevent ripple effects)

• clear contracts (public APIs and explicit types)

• local reasoning (understanding a unit without scanning the whole app)

Leading architects suggest treating readability as a team-level interface: the code is not written for computers, it’s written for other developers under time pressure.

Readability scales onboarding and refactoring

Teams with consistent conventions tend to see:

• faster onboarding (new devs find files quickly)

• smoother code reviews (less debate about style, more about behavior)

• safer refactoring (clear boundaries limit blast radius)

• better incident response (faster root-cause analysis)

Readability is also a compounding investment: each improvement makes the next improvement easier, because the system becomes more navigable.

Common strategies and their limits: from MVC and Atomic Design to DDD

If readability were only about “clean functions,” architecture wouldn’t matter. But in large frontend codebases, most readability problems are structural: where code lives, how it depends on other code, and how teams discover it.

Below are common approaches and how they affect readability:

| Approach | How it organizes frontend code | Common readability pitfalls |

|---|---|---|

| MVC / MVP | Layers by technical role (views, models, presenters/controllers) | Frontend often doesn’t map cleanly; view logic leaks into models; unclear boundaries as UI grows |

| Atomic Design | UI components by “atoms → molecules → organisms” | Great for design systems, but can obscure feature intent; business logic gets scattered across UI taxonomy |

| DDD / Clean Architecture | Domain-centric modeling with layered boundaries | Strong conceptual clarity, but can become heavy; teams struggle to map “domain” to UI workflows without strict conventions |

| Feature-Sliced Design | Slices by user value/features + domain entities, with layered rules | Requires discipline around public APIs and dependency direction; teams must learn the slicing vocabulary |

What these have in common: they try to create predictability. Readability thrives when a developer can answer:

• Where should new code go?

• Where do I look when something breaks?

• Which modules are allowed to depend on which?

• What is stable vs internal?

A useful mental model: horizontal layers vs vertical slices

Many teams start with horizontal layers:

• components/

• hooks/

• services/

• utils/

• store/

This looks neat—until features grow. Then every change touches many folders, and logic becomes fragmented. The code becomes “organized,” but not understandable.

Vertical slicing flips it:

• group code by feature or domain

• keep related UI + state + API calls together

• expose small, stable public APIs outward

This is where FSD is especially relevant: it provides a methodology for vertical slicing without losing the benefits of shared infrastructure and UI reuse.

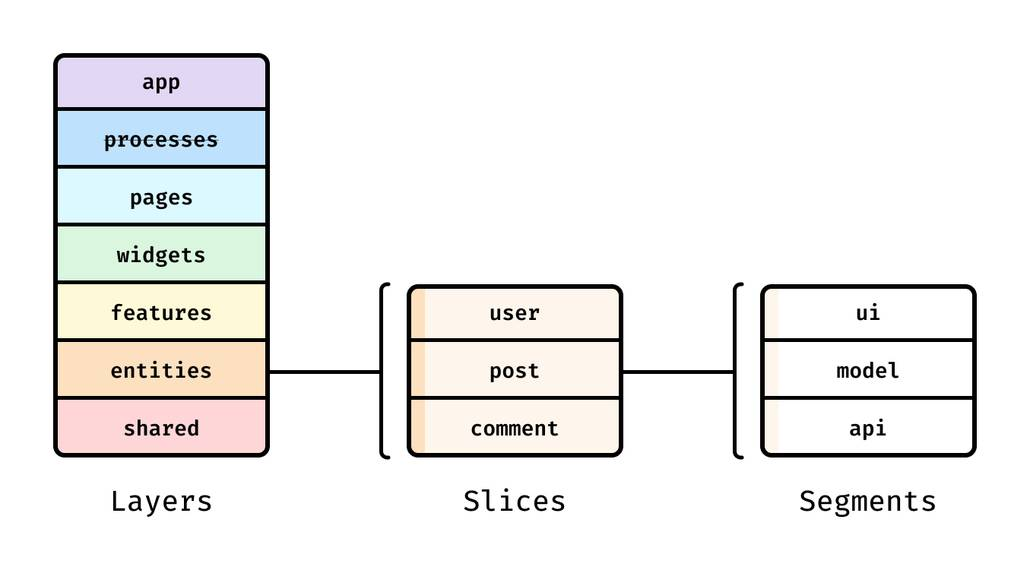

How Feature-Sliced Design turns readability into a repeatable system

Feature-Sliced Design (FSD) is a methodology for frontend architecture that makes readability predictable by design. As demonstrated by projects using FSD, the biggest win is not a single rule—it’s the combination of:

• layers (a dependency hierarchy)

• slices (feature/domain modules)

• segments (standard internal structure)

• public APIs (explicit boundaries)

The FSD layer model improves discoverability

A common FSD layering (from most global to most local value) looks like:

• app – app initialization, providers, global config

• processes – long-running flows spanning pages (optional)

• pages – route-level composition

• widgets – large UI blocks, page sections

• features – user actions and business capabilities

• entities – domain models and domain UI

• shared – generic, reusable primitives (UI kit, libs, API base, config)

Dependency direction is the readability guarantee: code usually depends “downwards” toward more generic layers, not upwards into higher-level composition.

A simple schema you can explain to any new teammate:

app

↓

pages

↓

widgets

↓

features

↓

entities

↓

shared

This makes navigation faster: if you’re fixing a bug in a user action, it’s probably in features/. If the bug is in a domain representation, it’s likely in entities/. If it’s a design system concern, it belongs in shared/ui.

Public APIs stop “dependency spaghetti”

A frequent readability killer is deep imports:

import { doThing } from "../../../features/a/model/private/helpers/doThing";

This couples consumers to internals. When internals move, everything breaks; when internals change, behavior becomes harder to reason about because boundaries are porous.

FSD encourages a public API per slice, often via an index.ts:

features/

auth/

index.ts # public API

model/

...

ui/

...

Consumers import:

import { login, LoginForm } from "features/auth";

This improves readability in two ways:

- Intent becomes visible at the import site (you see the slice, not the internal file).

- Refactoring becomes local (internals can move without rewriting the world).

A tangible example structure

Here’s an illustrative FSD-style structure for a typical product area:

src/

app/

providers/

router/

index.tsx

pages/

product-details/

ui/

index.ts

widgets/

product-summary/

ui/

index.ts

features/

add-to-cart/

model/

ui/

index.ts

toggle-favorite/

model/

ui/

index.ts

entities/

product/

model/

api/

ui/

index.ts

cart/

model/

index.ts

shared/

ui/

lib/

api/

config/

Notice how this structure answers common readability questions quickly:

• “Where is Add to cart logic?” → features/add-to-cart

• “Where is product domain mapping?” → entities/product

• “Where is the route composition?” → pages/product-details

• “Where do shared HTTP helpers live?” → shared/api

This predictability is what turns readability from an aspiration into a repeatable standard across teams.

The 7 rules to follow

Readable systems are built at multiple levels:

• line level (names, formatting)

• function/component level (flow, size, separation of concerns)

• module level (public APIs, boundaries)

• architecture level (slicing, dependency direction)

The rules below are designed to work together. You can adopt them incrementally, but they reinforce each other most strongly when combined with a structural methodology like FSD.

1) Name for intent, using consistent naming conventions

If you want self-documenting code, start with names. Names are the first documentation your readers see, and they appear everywhere: variables, functions, components, files, and exports.

Rule: Choose names that explain what and why, not how.

Practical naming guidelines

• Prefer domain vocabulary over technical vocabulary (invoice, subscription, trial, not data, item, payload).

• Use verbs for actions (fetchProducts, applyDiscount, toggleTheme).

• Use nouns for data (productList, discountRules, userProfile).

• For booleans, use is/has/can/should (isLoading, hasAccess, canEdit).

• Avoid ambiguous suffixes like Data, Info, Stuff, Manager.

• Prefer searchable, pronounceable names over abbreviations (selectedProductId beats selPid).

• In UI code, use consistent prefixes:

- event handlers:

onClick,onSubmit(props),handleSubmit(implementation) - derived values:

getTotalPrice,selectUserById - React hooks:

useCart,useAuth,useProductFilters

A quick “naming smell” test

If a name forces you to read its body to understand it, it’s a smell.

Bad (implementation-focused):

function process(items: Item[]) {

// ...

}

Better (intent-focused):

function calculateInvoiceTotals(lineItems: InvoiceLineItem[]) {

// ...

}

Naming across files and folders

Readable codebases have predictable naming conventions:

• File names reflect responsibility (product-card.tsx, use-cart.ts, cart.selectors.ts)

• One main export per file when practical (helps navigation)

• Avoid “misc” naming (helpers.ts, common.ts) unless scoped tightly to a slice

In FSD, naming becomes even clearer because the path carries meaning:

features/add-to-cart/ui/add-to-cart-button.tsx

entities/product/model/product.ts

shared/ui/button/button.tsx

Even before opening the file, you know where you are and why it exists.

2) Keep units small and cohesive; make the happy path obvious

Readability collapses when a function does five things, or when a component mixes fetching, mapping, formatting, rendering, and analytics in one file.

Rule: Each unit should have one reason to change (cohesion), and its main path should read top-to-bottom.

Tactics that reliably improve readability

• Use guard clauses to reduce nesting.

• Extract pure functions for data transforms.

• Separate UI composition from business rules.

• Prefer flat, linear flow over deeply nested conditionals.

• Keep components small enough to fit on one screen when possible.

A nested example that hides intent:

function submitOrder(order: Order) {

if (order.items.length > 0) {

if (order.user) {

if (!order.user.isBlocked) {

// ...

}

}

}

}

A readable version:

function submitOrder(order: Order) {

if (order.items.length === 0) return fail("Empty order");

if (!order.user) return fail("Not authenticated");

if (order.user.isBlocked) return fail("User blocked");

return placeOrder(order);

}

Keep React components readable

A common anti-pattern is a “God component”:

• reads route params

• fetches data

• manages local state

• renders complex UI

• triggers analytics

• contains domain rules

Instead, break by responsibility:

• Page composes widgets/features

• Widget shapes the UI area

• Feature performs the action

• Entity provides domain UI/models

• Shared provides generic components

This decomposition aligns naturally with FSD and keeps individual files understandable.

3) Make data flow and side effects explicit

Many readability bugs are not “wrong logic,” but hidden logic—especially in frontend apps where effects are triggered indirectly.

Rule: Prefer explicit parameters, explicit return values, and explicit side effects.

Common readability traps in frontend code

• implicit global state reads/writes

• effects triggered by unrelated renders

• “smart” utility functions with network calls

• hidden coupling via event buses or singletons

• selectors that do too much mapping

A readable pattern is to separate:

• pure computation (deterministic)

• side effects (IO, timers, subscriptions)

• orchestration (when/how effects run)

Example separation (illustrative):

// Pure: easy to test, easy to read

function getEligiblePromotions(cart: Cart, rules: Rules): Promotion[] {

// ...

}

// Side effect: isolated

async function fetchPromotionRules(): Promise<Rules> {

// ...

}

// Orchestration: explicit

async function loadPromotionsForCart(cart: Cart) {

const rules = await fetchPromotionRules();

return getEligiblePromotions(cart, rules);

}

Explicitness improves refactoring safety

When dependencies are explicit, you can refactor confidently because:

• you know what the unit needs

• you can mock dependencies in tests

• you can move the unit without dragging hidden globals

In FSD, explicitness becomes part of slice design: a feature should clearly depend on entities and shared, and the public API should reveal what is safe to consume.

4) Automate formatting and enforce a consistent style

Readable code is easier to scan when formatting is consistent. But consistency should not rely on personal discipline.

Rule: Automate formatting and linting so humans can focus on meaning, not bikeshedding.

A practical “readability toolchain”

• Prettier: automatic formatting (line breaks, spacing)

• ESLint: code quality rules (no unused vars, consistent imports, safe patterns)

• TypeScript (strict mode where feasible): stronger contracts and fewer ambiguous states

• EditorConfig: consistent whitespace across editors

• CI enforcement: the source of truth

This improves readability because:

• diffs become smaller and more focused

• code review discussions shift to architecture and behavior

• the codebase feels coherent even with many contributors

• scanning becomes faster (your eyes learn the pattern)

Style conventions that consistently help readability

• avoid overly clever one-liners in critical logic

• limit line length to encourage decomposition

• keep imports grouped and sorted

• prefer early returns over nested else blocks

• keep “configuration noise” away from core logic (e.g., move constants to shared/config or slice-level config)

Consistency isn’t about perfection; it’s about lowering friction so the code’s intent stands out.

5) Comment sparingly, but document decisions and constraints

Comments are part of code readability, but they’re also a source of rot. The best comments don’t narrate code; they preserve knowledge that code can’t reliably express.

Rule: Comments should explain why, constraints, and trade-offs—especially at boundaries.

When comments are genuinely valuable

• business rules that look arbitrary (“why 29 days?”)

• performance constraints (“must be O(n) due to list size”)

• security/privacy requirements (“do not log PII”)

• interoperability constraints (“API expects snake_case”)

• tricky edge cases and known pitfalls

• architectural decisions and reasoning

A useful comment captures intent and constraint:

// We keep the debounce at 250ms to avoid rate limiting on the search endpoint

// while still feeling responsive in low-latency regions.

const SEARCH_DEBOUNCE_MS = 250;

A low-value comment restates the obvious:

// Set loading to true

setLoading(true);

Prefer “decision records” for architectural choices

In mature projects, a lightweight ADR (Architecture Decision Record) approach boosts readability at the system level:

• what decision was made

• what alternatives were considered

• what trade-offs were accepted

• what constraints drove the choice

Even a short note inside a slice’s README or docs can prevent months of confusion later.

6) Expose a public API and hide implementation details

Readable architectures depend on boundaries. Without boundaries, everything can depend on everything, and comprehension requires full-system context.

Rule: Design modules around stable public APIs; keep internals private.

What a good public API does

• communicates the module’s purpose

• limits what consumers can rely on

• reduces coupling

• improves encapsulation

• makes refactors safer

A simple pattern:

features/payment/

index.ts # public API

ui/

model/

lib/

Public API (index.ts) might export:

• UI entry points (components)

• typed actions/use-cases (functions)

• stable types needed by consumers

But it should not export:

• internal helpers

• implementation types that change frequently

• deep folder structure details

Why this is a readability multiplier

When imports look like this:

import { PaymentForm } from "features/payment";

…the reader learns intent instantly. When imports look like this:

import { PaymentForm } from "features/payment/ui/forms/payment-form/private/payment-form";

…you’ve leaked complexity into every consumer, and every file becomes harder to scan.

FSD reinforces this rule by encouraging public APIs at the slice level and by treating boundary violations as architectural debt, not minor style issues.

7) Structure the codebase by features and domains, not by file types

At scale, folder structure is documentation. If your structure doesn’t encode meaning, your team will recreate meaning repeatedly in Slack threads, PR comments, and onboarding calls.

Rule: Organize by user value (features) and domain concepts (entities), with shared primitives isolated.

Why “type-based” folders fail over time

Folders like these often start clean:

• components/

• hooks/

• services/

• utils/

But they tend to become:

• huge and inconsistent

• hard to search (many similar names)

• unclear ownership (“who maintains utils/date.ts?”)

• coupled (everything imports everything)

You might have “organized” code, but not readable architecture.

A feature-first structure improves navigability

Feature-first organization makes the codebase mirror how the product works:

• checkout

• search

• favorites

• authentication

• profile

This fits naturally with FSD:

• features/ for user actions

• entities/ for domain models

• widgets/ and pages/ for composition

• shared/ for reusable infrastructure

A practical step-by-step adoption plan (even for existing codebases)

You don’t need a big-bang rewrite. A pragmatic migration often works like this:

- Pick one high-change area (e.g., “Add to cart” or “Search”).

- Create a slice in

features/with a clear public API. - Move only what you touch (boy-scout rule) into that slice.

- Extract domain logic into

entities/when it becomes reusable or central. - Push generic code downward into

shared/only when it’s truly cross-cutting. - Ban deep imports into slice internals (via lint rules and review).

- Repeat per feature until structure becomes the default.

This approach keeps delivery moving while steadily improving readability.

The outcome: readability becomes institutional

When structure is predictable, developers stop asking:

• “Where does this go?”

• “Is it okay to import this?”

• “Why is this logic duplicated?”

…and start spending more time on product value, correctness, and performance.

Conclusion

Readable code is built deliberately: it starts with intent-revealing naming conventions, stays understandable through cohesive units and explicit data flow, and scales through automation, thoughtful code comments, and strong module boundaries. The most sustainable improvements come from treating readability as an architectural concern—reducing coupling, increasing cohesion, and enforcing clear public APIs. Over time, adopting a structured methodology like Feature-Sliced Design (FSD) becomes a long-term investment in maintainability, onboarding speed, safer refactoring, and team productivity.

Ready to build scalable and maintainable frontend projects? Dive into the official Feature-Sliced Design Documentation to get started.

Have questions or want to share your experience? Visit our homepage to learn more!

Disclaimer: The architectural patterns discussed in this article are based on the Feature-Sliced Design methodology. For detailed implementation guides and the latest updates, please refer to the official documentation.