The Naming Convention That Will Save Your App

TLDR:

In large frontend apps, inconsistent naming turns every change into a hunt. This guide shows proven JavaScript/TypeScript and component naming practices, explains BEM and modern CSS naming approaches, and then introduces Feature-Sliced Design’s Layer–Slice–Segment convention—so your folder structure and public APIs make boundaries obvious, reduce coupling, and keep the codebase maintainable as your team grows.

Naming conventions are the fastest way to turn a growing frontend codebase from “search-and-hope” into a system you can navigate, refactor, and scale with confidence. When variable naming, component naming, and CSS schemes like BEM are inconsistent, every new feature increases coupling, onboarding time, and the risk of subtle regressions. Feature-Sliced Design (FSD) on feature-sliced.design adds the missing piece: a naming convention that encodes architectural boundaries, not just style.

Why naming conventions matter in JavaScript and TypeScript apps

A key principle in software engineering is that names are part of the API—even when you don’t export anything. Every identifier, file path, and folder name becomes a hint (or a trap) for the next person who reads the code.

When teams feel stuck, the causes are usually familiar:

• Low cohesion: modules mix responsibilities, so changes touch unrelated code.

• High coupling: a single edit ripples across many files and layers.

• Leaky abstractions: deep imports expose internals and make refactors dangerous.

• Vocabulary drift: the same concept has multiple names, or one name means multiple things.

That’s why naming conventions (naming standards, naming rules, or team nomenclature) are a scalability feature. They improve:

- Discoverability: faster search, faster onboarding, fewer “where does this live?” questions.

- Refactor safety: clearer boundaries, fewer surprise dependencies, fewer circular imports.

- Review quality: intent is visible at a glance, so reviewers focus on design, not decoding.

- Architecture integrity: structure stays consistent as contributors and features multiply.

A lightweight “naming debt” estimate

If 8 developers lose 10 minutes/day to confusing names and folder hunting, that’s ~6.5 hours/week, or ~300+ hours/year. Even if your numbers are half that, the ROI is still tangible.

A useful mental model: naming debt behaves like interest. Small inconsistencies compound because they multiply search paths, code paths, and mental paths.

The missing layer: names that encode boundaries

Local rules (camelCase, PascalCase, BEM) help, but large apps break down when modules are named without clear ownership. A robust naming strategy also defines:

• where code lives,

• what it owns,

• what it is allowed to import.

Feature-Sliced Design targets this architectural level while remaining compatible with common JavaScript and TypeScript style guides.

JavaScript and TypeScript naming conventions that reduce cognitive load

Good variable naming is about precision and domain language, not length. Many teams start from established references (popular industry style guides) and then adapt them to their domain vocabulary and TypeScript constraints.

| What you name | Recommended form | Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Variables & functions | camelCase | userId, formatCurrency(), fetchSession() |

| Classes, components, types | PascalCase | UserCard, SessionService, CheckoutState |

| Constants | UPPER_SNAKE_CASE | MAX_RETRIES, DEFAULT_TIMEOUT_MS |

Variables: meaning + qualifier + unit

A practical formula for variable naming conventions:

noun + qualifier + unit

Good:

const retryDelayMs = 250

const activeUserIds = new Set<string>()

const billingAddressForm = createBillingAddressForm()

Bad (semantic overload):

const data = ...

const temp = ...

const list = ...

A strong indicator of maintainability is whether a teammate can read a line and predict what it contains. Names like data and temp fail that test.

Collection and mapping names

Prefer names that encode structure:

• arrays/sets are plural: orders, selectedUserIds

• maps include key/value meaning: orderById, priceByCurrency

• grouped data uses “by” consistently: usersByRole, ordersByStatus

This reduces the chance of misusing a value and makes refactors safer.

Booleans: write them like assertions

Good:

const isAuthenticated = session !== null

const hasUnreadMessages = unreadCount > 0

const canEditProfile = role === 'admin' || role === 'owner'

Bad:

const ok = ...

const auth = ...

const editable = ...

Booleans are often used in conditions and UI state. Prefixing with is/has/can/should makes complex logic read like English.

Functions: verbs, side effects, and symmetry

A reliable naming scheme separates “compute” from “effect”:

• Pure computation: calculateTotal(), deriveShippingOptions()

• Side effects / I/O: saveDraft(), trackCheckoutStarted(), sendInvite()

• Data loading: fetchUser(), loadCheckout(), prefetchCatalog()

Pick one convention for handlers and stick to it:

• handleSubmit() (internal handler style)

• onSubmit() (event style)

Prefer symmetric pairs:

openModal() / closeModal()

enableFeature() / disableFeature()

subscribe() / unsubscribe()

Avoid vague verbs like process, manage, doStuff. These often hide mixed responsibilities and lead to “god functions.”

Async naming: make time explicit

In modern frontends, “async” is part of the contract. Good options:

• use verbs that imply I/O: fetch, load, save, sync

• or add a suffix when ambiguity is high: getUserAsync() (less common, but clear)

Bad:

getUser() // sometimes cached, sometimes fetches

getUser() // sometimes includes permissions, sometimes not

Better:

readUserFromCache()

fetchUserFromApi()

loadUserWithPermissions()

This reduces surprise side effects and improves testability.

Types and interfaces: name the concept

Good TypeScript naming conventions focus on meaning:

type User = { id: string; email: string }

type UserId = string

type CheckoutStatus = 'idle' | 'loading' | 'success' | 'error'

Helpful suffixes (when they clarify a boundary):

• Params, Input, Output

• DTO (transport shape)

• Result (structured outcome)

• State (UI/store state)

Bad (encoding the mechanism instead of the concept):

type IUser = ...

type UserInterface = ...

type UserType = ...

Leading architects suggest using a ubiquitous language: if product says “workspace,” don’t call it “tenant” in code.

Naming errors and results

Frontends benefit from explicit error naming, especially with domain logic:

class PaymentDeclinedError extends Error {}

type LoadUserResult = { ok: true; user: User } | { ok: false; error: Error }

Clear names reduce coupling between UI and failure modes because the UI can handle “declined” vs “network” differently.

Files and folders: choose a case and automate it

Common file naming conventions:

• kebab-case for files/folders: user-card.tsx, checkout-summary.vue, use-auth.ts

• PascalCase only when your framework tooling expects it

Consistency matters more than the choice. Automate it with linting and pre-commit hooks so the convention survives team growth.

Component naming in React, Vue, and Svelte: files, props, hooks, and events

Component naming is where teams either gain speed or accumulate silent debt. The goal is to make "what is this?" obvious without opening three files.

Components: nouns for UI, domain words for intent

Good:

• UI nouns: UserCard, PriceTag, CheckoutSummary

• Intentful widgets: AddToCartButton, SendInviteForm, ApplyPromoCodeForm

Bad (too generic):

List

Item

Form

Modal

Better:

OrderList

ShippingAddressForm

DeleteWorkspaceModal

A simple rule: if the name still makes sense after you remove the surrounding folder context, it’s probably good.

Files and exports: optimize for search and stable imports

A scalable convention:

• file name describes the exported component: user-card.tsx exports UserCard

• prefer named exports (better autocomplete, safer refactors)

• use index.ts as a public API, not a shortcut to export everything

Good:

// user-card.tsx

export function UserCard(...) {}

// entities/user/index.ts (public API)

export { UserCard } from './ui/user-card'

Risky (blurs boundaries and creates accidental dependencies):

// index.ts

export * from './ui'

export * from './model'

export * from './api'

Props and events: consistent grammar

A pragmatic naming convention for props:

• data as nouns: user, orders, price

• callbacks as onX: onSubmit, onCancel, onSelectOrder

• booleans as is/has/can: isLoading, hasError, canEdit

Also consider units and semantics:

• timeoutMs, maxItems, initialValue

• avoid ambiguous props like value unless it is the central value

React conventions that scale

• components: PascalCase

• event props: onX

• render props: renderX

• state components: prefer explicit names like CheckoutSummarySkeleton, UserCardEmpty

Vue conventions that prevent friction

• components: PascalCase in SFC files (CheckoutSummary.vue)

• props: camelCase in script, kebab-case in templates

• emitted events: standardize grammar (submit, cancel, update:modelValue)

Example (predictable domain naming):

<UserEmailForm :initial-email="email" @email-submitted="..." />

Svelte conventions that stay readable

• components: PascalCase files (UserCard.svelte)

• stores: clear nouns (cartStore) and readable derived names (isAuthenticated)

• event dispatchers: use domain words (checkoutConfirmed, promoApplied) rather than UI words (buttonClicked)

Hooks and composables: encode scope and ownership

Good:

useAuth()

useCheckoutState()

useUserPermissions()

Bad:

useData()

useHelper()

A hook named useUser() placed in a global “helpers” folder tends to grow without boundaries. Precise naming plus a clear location reduces scope creep.

Good and bad component naming examples

Bad (structure hides intent):

components/

common/

Modal.tsx

Form.tsx

List.tsx

pages/

Page.tsx

Good (intent + boundary):

pages/

checkout/

ui/

CheckoutPage.tsx

features/

apply-promo-code/

ui/

ApplyPromoCodeForm.tsx

entities/

order/

ui/

OrderSummary.tsx

shared/

ui/

modal/

modal.tsx

The “good” version is more searchable, more reviewable, and easier to refactor.

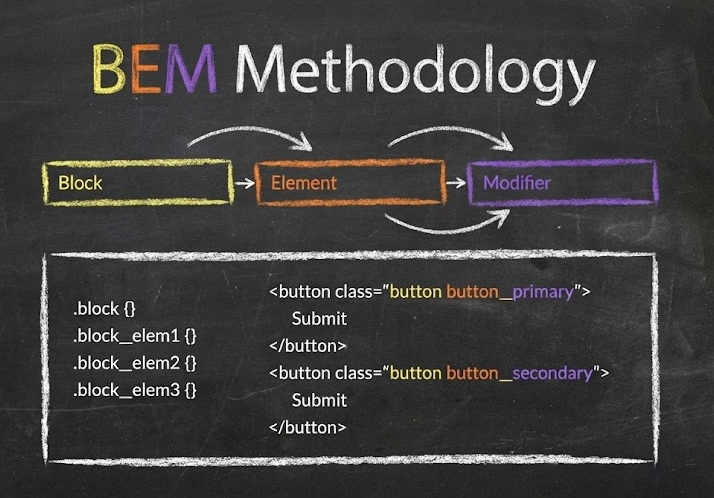

CSS naming conventions: BEM, scoped styles, and utilities

CSS is where naming conventions prevent collisions and make intent visible in DevTools.

BEM: structure and state in the name

Example:

.product-card {}

.product-card__title {}

.product-card__price {}

.product-card--compact {}

Use domain-driven block names (product-card), descriptive elements (__title), and stateful modifiers (--active, --compact). Avoid presentational names like .blue-card that break during redesigns.

A practical BEM checklist:

• blocks represent components or UI regions

• modifiers represent state/variant (--disabled, --primary, --error)

• don’t encode layout (--left-column) unless it is a real variant

Scoped CSS / CSS Modules: local names still need meaning

Even with scoping, prefer:

.cardHeader

.priceRow

.errorMessage

over:

.root

.container

.item

Scoped CSS reduces collisions, but it doesn’t solve readability. Naming still matters for debugging and onboarding.

Utility-first: naming shifts to tokens and variants

With utility-first CSS, your naming scheme often lives in:

• design tokens (--color-text-primary, --space-3, --radius-sm)

• variants (primary, danger, ghost, sm, lg)

• state (isDisabled, isActive)

The rule is still the same: make intent readable. If a utility chain becomes “string soup,” extract it into a component or variant helper.

| Approach | What it optimizes | Naming implication |

|---|---|---|

| BEM | explicit structure & state | block__element--modifier as a shared grammar |

| Scoped / Modules | collision resistance | class names should remain meaningful |

| Utility-first | speed & consistency | naming moves to tokens, variants, and state |

From folders to boundaries: naming modules so architecture stays coherent

Most “unscalable” frontends share a pattern: a few folders turn into junk drawers (utils, common, sharedStuff). That’s not a talent problem. It’s an absence of boundary naming.

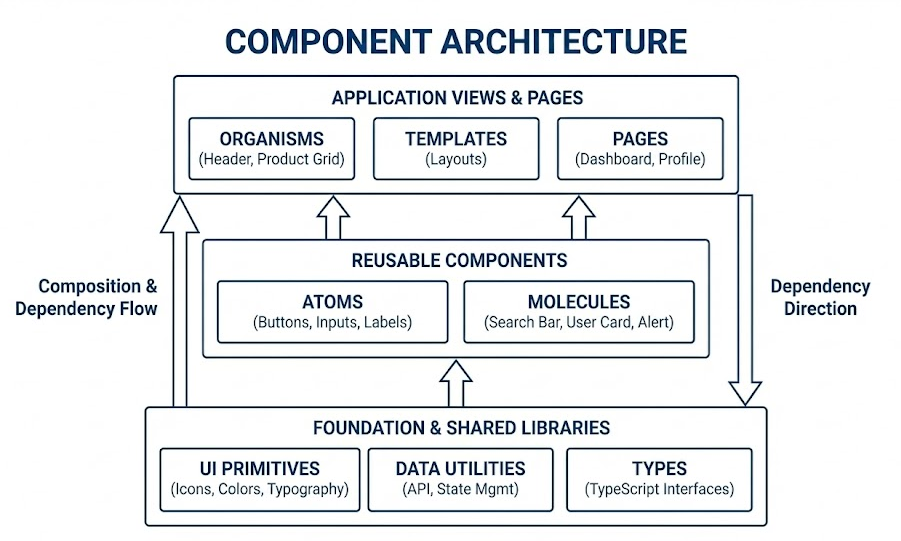

What popular methodologies imply for naming

| Methodology | Organizing principle | Common naming outcome |

|---|---|---|

| MVC / MVP | technical roles | models/, views/, controllers/ |

| Atomic Design | UI taxonomy | atoms/, molecules/, organisms/ |

| Feature-Sliced Design | responsibility + layers | features/, entities/, shared/, pages/, widgets/, app/ |

MVC/MVP can work for small apps, but horizontal slicing tends to scatter one domain concept across multiple technical folders. Refactors become “find every piece of orders logic everywhere.”

Atomic Design is strong for design systems and UI libraries, but product teams often struggle when business logic doesn’t map cleanly to atoms/molecules. Naming debates shift toward UI shape rather than domain purpose.

Domain-Driven Design (DDD) adds a useful lens: name things after the domain and keep boundaries explicit. Feature-Sliced Design fits that mindset well, because slices map naturally to domain concepts and capabilities.

Public API: the simplest anti-spaghetti rule

Instead of deep importing internals:

import { createSession } from '../entities/user/model/session'

prefer importing from a slice entry point:

import { createSession } from '@/entities/user'

This reduces coupling and makes refactoring safer, because internal paths can change without breaking the world.

The “dependency cone” you can enforce

Describe your architecture as a dependency rule:

• shared should not depend on business code

• entities may depend on shared

• features may depend on entities and shared

• widgets/pages/app compose above, but avoid pushing business logic upward

Even without tooling, this language improves architecture conversations. With tooling, it becomes enforceable.

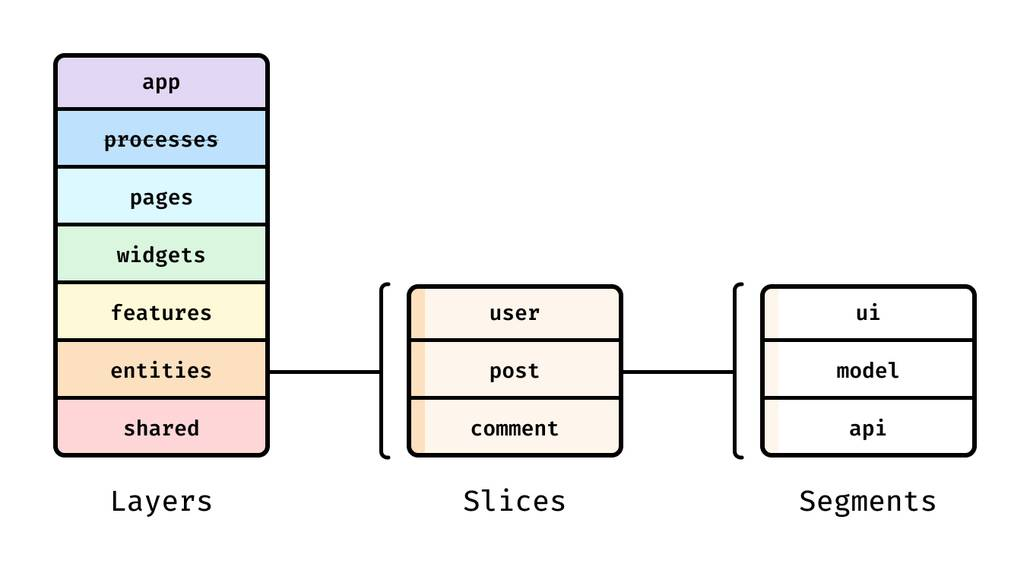

The convention that saves apps: Layer–Slice–Segment in Feature-Sliced Design

"The naming convention that will save your app" is not a clever casing rule. It's Layer–Slice–Segment, a path grammar from Feature-Sliced Design that makes architectural intent visible in every import.

The three-part grammar

- Layer: responsibility level (

shared,entities,features,widgets,pages,app). - Slice: a cohesive domain concept or capability (

user,order,auth-by-email). - Segment: technical role inside the slice (

ui,model,api,lib,config).

Example imports:

import { LoginForm } from '@/features/auth-by-email'

import { UserCard } from '@/entities/user'

import { Button } from '@/shared/ui/button'

Even without opening files, you can infer responsibility, ownership, and likely dependencies.

A tangible directory structure

src/

app/

providers/

routes/

styles/

pages/

checkout/

ui/

model/

index.ts

widgets/

header/

ui/

index.ts

features/

auth-by-email/

ui/

model/

api/

index.ts

apply-promo-code/

ui/

model/

api/

index.ts

entities/

user/

model/

api/

ui/

index.ts

order/

model/

api/

ui/

index.ts

shared/

ui/

button/

modal/

api/

lib/

config/

assets/

This structure is intentionally boring. That’s a feature: predictable code is easier to change.

Segment naming conventions: stable, predictable buckets

• ui/ — components and styles

• model/ — state, rules, types, selectors

• api/ — requests, adapters, DTO mapping

• lib/ — slice-local helpers

• config/ — constants and configuration

When segment names are stable, engineers can “guess the path” correctly. That reduces time spent searching and improves onboarding.

Public API per slice: the import gate

In FSD, each slice exposes a minimal public API (commonly via index.ts):

// entities/user/index.ts

export { UserCard } from './ui/user-card'

export { useUser } from './model/use-user'

export type { User } from './model/types'

Consumers import from the slice root, not from deep internals:

import { UserCard } from '@/entities/user'

This increases encapsulation and protects refactors.

Good vs bad imports (the boundary is in the name)

Bad (bypasses the public API):

import { selectUser } from '@/entities/user/model/selectors'

Good (depends on the slice contract):

import { selectUser } from '@/entities/user'

The “good” import communicates architectural intent. It also makes it easier to apply automated refactors (because there are fewer path variants to chase).

Feature vs entity: naming that clarifies responsibility

• Entity: long-lived business concept (user, order, product).

• Feature: user action/capability (add-to-cart, apply-promo-code, auth-by-email).

• Widget: reusable composition (header, sidebar).

• Page: route-level composition (checkout).

• Shared: generic building blocks (button, http-client, date-format).

As demonstrated by projects using FSD, this separation helps to mitigate common challenges: accidental coupling, unclear ownership, and unbounded “common” folders.

How to standardize and enforce naming conventions across a team

Naming conventions only create value when they are consistent. The good news is you can make consistency the default.

Step 1: write a one-page naming charter

Include:

- identifier casing rules (camelCase, PascalCase, constants)

- file/folder naming conventions (

kebab-case, test file names, story names) - CSS naming approach (BEM/modules/utilities)

- FSD layer/slice/segment rules

- public API and import boundaries

- a few good/bad examples from your repo

Keep it short enough to be read in under 10 minutes.

Step 2: enforce with tooling (so humans can focus on design)

A pragmatic baseline:

• ESLint + TypeScript rules for naming and imports

• Stylelint for CSS naming

• Prettier for formatting

• CI checks and pre-commit hooks for consistent enforcement

Prioritize rules that prevent costly coupling:

• ban deep imports into other slices

• require imports from slice public APIs

• keep shared free of business-specific logic

Here's a simplified "import boundary" rule expressed as configuration intent:

// pseudo-config (conceptual)

// - allow '@/entities/user' but disallow '@/entities/user/model/*'

// - disallow imports from higher layers into lower layers

Even a partial rule set reduces drift.

Step 3: templates, generators, and code review checklists

Provide scaffolds like:

• features/<feature>/{ui,model,api,index.ts}

• entities/<entity>/{ui,model,api,index.ts}

Then reinforce with a lightweight checklist:

• Does the name match the domain concept?

• Is the code in the right layer (entity vs feature)?

• Are imports using the public API?

• Is shared staying generic?

Step 4: migration-by-touch (no rewrite required)

A safe migration sequence:

- create top-level FSD layers

- apply naming conventions for new code first

- refactor hotspots when you touch them (boy scout rule)

- add public APIs gradually, starting with your most reused slices

This keeps delivery moving while steadily reducing technical debt.

Conclusion

Clear naming conventions make frontend teams faster because they reduce uncertainty, improve discoverability, and keep modularity intact as the codebase grows. Strong variable naming and component naming improve local readability, while CSS naming schemes like BEM, scoped styles, or token-driven utilities clarify intent and prevent collisions. The long-term win comes from naming modules by responsibility and enforcing boundaries with a public API, so refactoring becomes routine instead of risky.

Feature-Sliced Design brings these ideas together with the Layer–Slice–Segment convention: folder paths communicate ownership, imports communicate architecture, and slices stay cohesive. Adopting a structured architecture like FSD is a long-term investment in code quality and team productivity because it lowers coupling, increases isolation, and shortens onboarding. Start small: apply the rules to new code, add import-boundary linting, and migrate “by touch” as you work in existing areas.

Ready to build scalable and maintainable frontend projects? Dive into the official Feature-Sliced Design Documentation to get started.

Have questions or want to share your experience? Visit our homepage to learn more!

Disclaimer: The architectural patterns discussed in this article are based on the Feature-Sliced Design methodology. For detailed implementation guides and the latest updates, please refer to the official documentation.