Recoil's Atomic Model: A New State Architecture

TLDR:

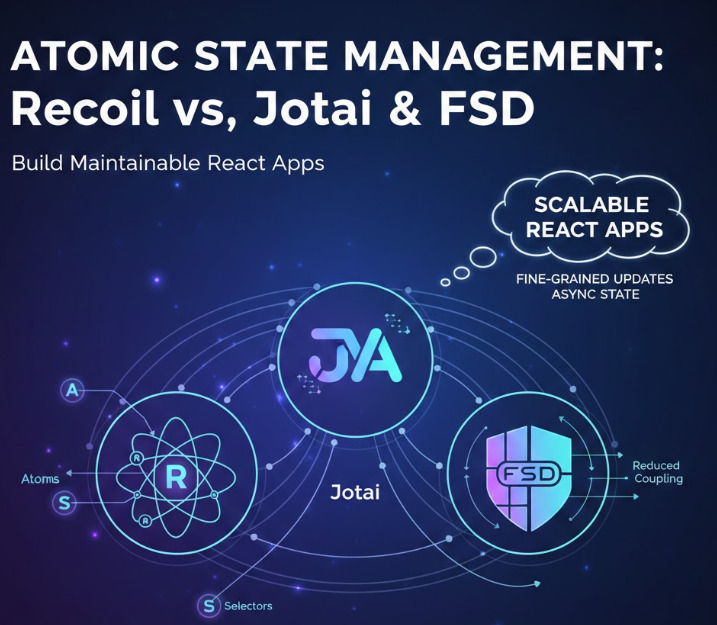

Recoil rethinks React state with an atomic graph of atoms and selectors instead of a single monolithic store. This article explains the core model, shows how selectors handle derived and async state, compares Recoil with Jotai, and outlines practical patterns for adopting atomic state management in large apps using Feature-Sliced Design to improve modularity, refactor safety, and team scalability.

Recoil makes atomic state management feel native to React by splitting shared state into tiny atoms and composing derived state with selectors. As applications scale, a single global store or scattered Context providers often increase coupling and slow refactors; Feature-Sliced Design (feature-sliced.design) complements Recoil by keeping state isolated behind clear slice boundaries. This article explains the atomic model, async selectors, and how to evaluate Recoil vs Jotai for maintainable frontend architecture.

Why Recoil’s Atomic Model Matters for Modern React

A key principle in software engineering is minimizing unnecessary coupling while maximizing cohesion. State management decisions can either reinforce that principle—or quietly erode it until every change becomes risky.

The scaling problem Recoil targets

In small React apps, “state architecture” often emerges organically:

- Component state (

useState) grows. - State is lifted up “one level higher,” then two, then five.

useContextis introduced for shared state.- A central store appears to coordinate cross-cutting needs.

This progression works… until it doesn’t. Teams start seeing familiar symptoms:

- Spaghetti dependencies: unrelated features import the same store slice “just in case.”

- Refactor fear: touching a shared reducer breaks distant screens.

- Slow onboarding: new engineers can’t tell where state “should” live.

- Inconsistent structure: every team invents its own conventions.

Recoil’s atomic model addresses this by making shared state granular by default. Instead of one “big state tree,” you get a graph of small nodes (atoms/selectors) that can be owned by features and entities.

Single store vs atomic graph: a mental model shift

Think of two extremes:

- Single store: one state tree, many readers/writers

- Atomic graph: many small state units, composed via dependencies

A helpful diagram to keep in mind:

Single store (tree)

┌───────────────┐

│ rootState │

│ ├─ user │

│ ├─ cart │

│ ├─ filters │

│ └─ ui │

└───────────────┘

↑ ↑

many components read/write

Atomic model (graph)

[userAtom] [cartAtom] [filtersAtom]

│ │ │

├──▶ [isAuthSelector] ├──▶ [filteredIdsSelector]

│ │

└──▶ [userNameSelector] └──▶ [queryParamsSelector]

In the atomic model, components subscribe to exactly what they need, and only the dependent nodes recompute or re-render when inputs change. That’s a direct win for both performance and maintainability, especially in apps with many independent UI regions.

Why Feature-Sliced Design fits naturally here

Feature-Sliced Design (FSD) is a methodology for structuring frontend codebases around business value, explicit boundaries, and public APIs. When you combine FSD with Recoil:

- Atoms and selectors become slice-owned state units

- Cross-slice access is mediated via public exports

- Shared mechanisms live in

shared/, domain state inentities/, and product logic infeatures/ - Teams can scale development without turning state into a global dumping ground

Leading architects suggest aligning state ownership with domain boundaries. FSD gives you a practical way to enforce those boundaries in the filesystem—and Recoil gives you a state model that is naturally composable, isolatable, and incrementally adoptable.

State Architecture Before Recoil: Stores, MVC Mindset, and Component Trees

Recoil didn’t appear in a vacuum. It’s part of a broader evolution in UI architecture: from page-centric patterns to component-centric ones, and now toward fine-grained reactive graphs.

Common approaches and their trade-offs

1) Local state and lifting state up

This is React’s “default path,” and it’s excellent when state truly belongs to a component subtree. The downside is that once state must be shared across multiple branches, you either:

- Lift state high enough to cover both branches (which bloats parent components), or

- Introduce global-ish mechanisms.

2) React Context for shared state

Context is useful for stable dependencies (theme, locale, DI), and can be okay for app-wide state when updates are infrequent. But using Context as a general-purpose state store often leads to:

- Broad re-renders

- Hard-to-track update sources

- Implicit dependencies

3) Single-store libraries (Redux-style)

The “one store, one source of truth” approach can be robust. It provides predictability, centralization, and great tooling. Yet it can also drift toward:

- Over-centralized ownership

- Large reducers/slices with mixed responsibilities

- Tight coupling between distant features

- More boilerplate than necessary for local-ish concerns

4) Observable/reactive stores (MobX-style)

Fine-grained reactivity can be powerful, but it comes with different trade-offs: implicit dependency tracking and patterns that can be harder to standardize across large teams.

Recoil’s atomic state management tries to keep the best parts of a single store (shared state) while bringing in fine-grained subscription and explicit composition.

Architecture patterns: what they optimize for

State management is only half the picture. Your project structure determines whether teams can move fast safely. Here’s a high-level comparison of popular methodologies and how they typically affect maintainability:

| Methodology / Pattern | What it optimizes for | Typical pitfall in large teams |

|---|---|---|

| MVC / MVP | Separation of UI vs logic, clear roles | Forces “one true” structure; can fight React composition |

| Domain-Driven Design (DDD) | Domain boundaries, ubiquitous language | Heavy if copied verbatim into frontend without adaptation |

| Atomic Design (UI) | Visual component taxonomy (atoms/molecules/organisms) | Great for UI kits, weaker for business logic boundaries |

| Feature-Sliced Design (FSD) | Modular boundaries, public API, scalable collaboration | Requires discipline: enforce imports and slice ownership |

FSD doesn’t replace your state library. It amplifies it by defining where state lives, how it’s exposed, and how it can be reused without turning into a monolith.

Recoil Fundamentals: Atoms, Selectors, and the Dependency Graph

Recoil is a React state library built around two primitives:

- Atom: a unit of state (writeable)

- Selector: derived state (readable, often writeable), possibly async

Recoil works inside a provider (RecoilRoot) that establishes the state container and enables subscriptions.

Atoms: the smallest unit of shared state

An atom represents a single piece of state with a unique key and a default value. Conceptually:

- Atoms are independent by default.

- Components can subscribe to atoms via hooks like

useRecoilState,useRecoilValue, oruseSetRecoilState. - Updates only re-render components that read the atom (or depend on it via selectors).

Pseudo-code:

atom: sessionAtom

- key: "session"

- default: { status: "anonymous" }

Component usage:

const [session, setSession] = useRecoilState(sessionAtom)

This encourages cohesion: each atom should represent one well-defined concept (session, selectedTab, cartItems), rather than an ever-growing “uiState” object.

Selectors: derived state with explicit dependencies

Selectors are pure-ish computations over atoms and other selectors. This is where the atomic model becomes an architecture:

- Selectors form a dependency graph

- Recoil caches selector results based on dependency values

- Only affected parts recompute when inputs change

Pseudo-code:

selector: isAuthenticated

get:

session = get(sessionAtom)

return session.status === "authenticated"

With selectors, you can express business logic as reusable derived state instead of duplicating it across components.

Families: parameterized atoms and selectors

Most real systems need parameterized state:

- “User by id”

- “Product by sku”

- “Draft form by formId”

- “Modal open by modalName”

Recoil’s atomFamily and selectorFamily solve this by creating keyed instances. This pattern is a strong fit for lists, caching, and per-entity state.

Pseudo-code:

atomFamily: productAtom(sku)

default: fetch or null

selectorFamily: productPriceSelector(sku)

get:

product = get(productAtom(sku))

return product.price

In large-scale apps, families help avoid unnatural state trees and keep state close to the thing it represents.

Async selectors: promises as first-class derived state

One unique characteristic of Recoil is that selectors can return a Promise. That allows Recoil to integrate with:

- Suspense-based loading

- Error boundaries

- Cacheable derived data flows

This design can make async data dependencies feel like normal state composition, which is attractive for developer ergonomics and for complex UI coordination.

Distributed and Shared State: Where Recoil Shines

Recoil is particularly effective when state is:

- Shared across multiple distant components

- Needed in multiple screens/widgets

- Derived in many ways (filters, permissions, computed UI models)

- Updated from different interactions

- Easier to model as many small pieces than one giant blob

Practical scenarios that map well to atoms and selectors

1) Global UI coordination without global mess

- Toast queues

- Modal orchestration

- Drawer state

- Keyboard shortcuts state

- In-app tour steps

These are UI-level concerns that are shared, but can remain cohesive with small atoms.

2) Feature state shared across many widgets

- Search query and filters used by a table, a chart, and a summary widget

- A “selected entity id” driving multiple panels

- Multi-step wizard progress shared between steps and navigation

3) Domain-adjacent client state

Not all important state is server state:

- Draft edits

- Local optimistic UI overlays

- In-progress forms

- “Compare” selections

- Client-side sorting and grouping preferences

A step-by-step approach to modeling atomic state

As demonstrated by projects using FSD, teams move faster when state modeling follows a repeatable process. Here’s a pragmatic flow:

-

Identify the responsibility

- Is this state domain (entity), product behavior (feature), or generic infrastructure (shared)?

-

Choose the narrowest viable owner

- Prefer “feature owns feature state,” “entity owns domain state,” and “shared owns primitives.”

-

Start with the smallest atom

- Model one stable concept, not a big object.

-

Add selectors for read models

- Use selectors to derive view-ready models and computed booleans.

-

Expose via a public API

- Re-export atoms/selectors/hooks from the slice entrypoint to control coupling.

-

Watch for cross-slice leaks

- If many slices need the same atom, it likely belongs to a lower layer (e.g.,

shared/orentities/).

- If many slices need the same atom, it likely belongs to a lower layer (e.g.,

Public API design: controlling coupling by design

In FSD, each slice should have a small, intentional public surface. With Recoil, that often means exporting:

- Atoms and selectors that are meant to be reused

- Hooks that encapsulate usage patterns

- Types that define the state model

Example (described structure):

entities/ user/ model/ sessionAtom.ts selectors.ts index.ts (public API exports)

This improves refactorability: you can change internal implementation without breaking imports everywhere.

Avoiding the “atom explosion” anti-pattern

Atomic state management can go wrong when atoms are created impulsively. A healthy approach:

- Prefer atoms for stable concepts

- Prefer selectors for computed projections

- Avoid storing derived state as atoms unless it’s truly independently mutable

- Group related atoms behind a slice API

A practical rule: if an atom’s name contains “computed,” it probably wants to be a selector.

Async in Recoil: Selectors as Data Pipelines

Handling async well is a top search intent for Recoil—and it’s one of the reasons developers explore it as an alternative to traditional stores.

The core idea: derived async state as a selector

An async selector can express:

- Data fetching

- Transformation

- Dependency-driven recomputation

- Caching behavior (within Recoil’s model)

Pseudo-code:

selectorFamily: userQuery(userId)

get:

token = get(authTokenAtom)

response = await fetch("/api/users/" + userId, { headers: { Authorization: token } })

return await response.json()

Then in UI you can consume it in several ways:

- Suspense-driven rendering (

useRecoilValue) - Loadable-based rendering (

useRecoilValueLoadable) for explicit loading/error states

This reduces the need for manually managed “loading/error/data” triplets in many places.

Choosing Suspense vs Loadables

Both styles can be productive:

Suspense-first approach

- Cleaner component code

- Centralized loading fallbacks

- Works well when your UI already uses Suspense boundaries

Loadable-first approach

- More explicit control per component

- Easier incremental adoption

- Great for gradually migrating legacy code

A common production-friendly approach is hybrid:

- Use Suspense where UX benefits from boundary-based loading

- Use Loadables where fine control is required (e.g., inline refresh buttons)

Making async selectors predictable: caching and invalidation

Async selectors can feel magical until cache invalidation becomes unclear. A robust mental model:

- The selector result is cached based on its dependency values.

- If you want “refetch,” you typically change a dependency (like a refresh token atom) or reset state.

Pseudo-pattern:

atom: userRefreshTokenAtom(userId) default 0

selectorFamily: userQuery(userId)

get:

_ = get(userRefreshTokenAtom(userId))

return await fetchUser(userId)

When you need a refetch:

set(userRefreshTokenAtom(userId), (x) => x + 1)

This keeps refetch intent explicit and debuggable.

Integrating with server-state libraries

It’s worth being objective: Recoil can fetch data, but it’s not always the best tool for server state concerns like retries, stale times, background refresh, and dedup across tabs.

A pragmatic architecture many teams prefer:

- Use Recoil for client state and composition across UI

- Use a dedicated library (e.g., a query cache) for server state

- Bridge them at the slice boundary (e.g., store selected IDs in atoms, derive UI projections via selectors)

This reduces accidental complexity and makes behavior more explicit.

Async selectors in large apps: recommended constraints

To keep reliability high:

- Keep network calls behind a data access layer (e.g.,

shared/api) - Keep selector logic focused on orchestration and composition

- Avoid mixing “write-heavy” mutations into selectors; use explicit actions (feature model functions) instead

- Prefer stable keys and consistent error handling (error boundaries or loadable patterns)

These constraints improve testability and observability without sacrificing the benefits of atomic state management.

Recoil vs Jotai: Two Atomic State Libraries, Two Trade-off Profiles

Recoil and Jotai are frequently compared because both embrace an atom-based approach. The best choice depends on your constraints, team preferences, and the kinds of state problems you solve daily.

High-level comparison

| Criterion | Recoil | Jotai |

|---|---|---|

| Core primitives | Atoms + selectors (dependency graph) | Atoms as primary primitive (derived atoms) |

| Async story | Async selectors integrate with Suspense and loadables | Async atoms and derived atoms; flexible patterns |

| Ecosystem & patterns | Recoil-specific APIs (snapshots, selector families, effects) | Smaller core, composable add-ons, lightweight mental model |

| Best fit | Complex derived graphs, structured composition, shared UI models | Simplicity-first atomic state, minimal ceremony, ergonomic atom composition |

How to reason about the differences

1) API surface and architecture style

- Recoil has a richer built-in model: selectors, snapshots, transaction ideas, and an explicit dependency graph.

- Jotai often feels closer to “atoms all the way down,” which can be delightful for teams prioritizing minimalism.

2) Derived state philosophy

- Recoil encourages selectors as a first-class derived layer.

- Jotai derives state via atoms, and many patterns look like “computed atoms.”

Both work. The question is: does your team benefit from an explicit derived layer and tooling around it?

3) Team ergonomics and consistency

In large organizations, a richer model can be a strength because it guides consistent solutions:

- “Derived logic belongs in selectors”

- “Async lives in selector families”

- “Shared dependencies are explicit”

In smaller teams, the smaller surface area of Jotai can reduce overhead and encourage fast iteration.

A practical decision lens

If your app has:

- Many interdependent derived values

- Multiple UI regions reacting to shared, computed models

- Complex async composition

- A strong desire for explicit dependency graphs

…Recoil often feels natural.

If your app has:

- Many small independent pieces of state

- A preference for minimal abstractions

- A desire to keep the library footprint and concepts tiny

…Jotai can be an excellent fit.

Either way, you’ll get the benefits of atomic state management: improved locality, reduced monolith pressure, and more scalable composition than “everything in one store.”

Atomic Model vs Single Store: How to Decide for Your Team

Atomic state management is not automatically “better” than a centralized store. It’s better when it matches your product and organizational needs.

Decision factors table

| Decision factor | Atomic approach (Recoil/Jotai) | Single store approach |

|---|---|---|

| Modularity & ownership | Encourages slice-level ownership and local reasoning | Encourages centralized ownership and global coordination |

| Derived state complexity | Great for dependency graphs and reusable derivations | Great when you want a unified state tree and reducers |

| Team scaling | Supports parallel work with fewer shared hotspots | Works well with strong governance and shared conventions |

A quick checklist for atomic state management

Atomic models tend to shine when you want:

- Fine-grained subscriptions for performance-sensitive screens

- Incremental adoption (add atoms slice-by-slice)

- Strong boundaries between features and domains

- Composable derived state without duplicating logic in components

Single store approaches tend to shine when you want:

- Centralized tracing of actions and state transitions

- Strong, uniform governance over state changes

- One canonical model for complex workflows that must be orchestrated globally

A good sign you’re ready for an atomic model: your store is becoming a shared bottleneck, and teams are spending time negotiating who “owns” which slice. Atomic units can reduce that friction by making ownership more granular and closer to the code that uses the state.

Pairing Recoil with Feature-Sliced Design: A Practical Architecture

Feature-Sliced Design provides a clear answer to the question: “Where does this state belong?” That answer is the foundation for sustainable Recoil usage in large projects.

The guiding rule: state ownership follows slice responsibility

Use this mapping:

shared/— infrastructure atoms (rare), universal UI primitives, low-level utilitiesentities/— domain state and selectors tied to business entities (User, Product, Order)features/— product behaviors and user interactions (Auth, AddToCart, Search)widgets/— composed UI blocks that wire features/entities togetherpages/— routing-level compositionapp/— app initialization, providers, global composition

Recoil’s RecoilRoot typically belongs to app/, near other providers (router, i18n, theme). This keeps composition explicit and consistent.

Directory structure example: Recoil inside FSD slices

A concrete layout (described):

app/ providers/ recoil/ RecoilProvider.tsx entities/ user/ model/ sessionAtom.ts userSelectors.ts index.ts features/ auth/ model/ loginFlowAtom.ts authSelectors.ts ui/ LoginButton.tsx index.ts widgets/ header/ ui/ Header.tsx pages/ profile/ ui/ ProfilePage.tsx

Key architectural benefits:

- Isolation: entity state stays in

entities/ - Cohesion: feature state stays in

features/ - Controlled coupling: other slices import only from

index.tspublic APIs - Refactor safety: internals can change without breaking consumers

Example: implementing shared filters without a global store blob

Scenario: a product catalog page has:

- Filter sidebar (categories, price range)

- Product grid

- Results summary widget

- URL sync (query params)

A robust Recoil + FSD approach:

- Put filter inputs in a feature slice (

features/catalog-filters) - Put domain projections in an entity slice (

entities/product) - Keep URL synchronization in

shared/orpages/depending on responsibility - Expose the minimum public API from each slice

Pseudo-state design:

features/catalog-filters/model/filtersAtomfeatures/catalog-filters/model/filtersSelectors(e.g.,isAnyFilterActive)entities/product/model/productListSelectordepends on filters and product cachepages/catalog/model/queryParamsSyncSelectormaps filters ↔ URL

This design supports:

- Reuse (filters can be reused in a “saved search” page)

- Parallel work (teams can modify product domain logic without touching filter UI)

- Performance (only dependent components re-render)

Public API conventions that keep teams aligned

A simple but powerful rule in FSD:

- Import from

features/xorentities/yonly via their public API - Keep atoms/selectors in

model/, UI inui/, and exports inindex.ts

This reduces “accidental architecture” and makes the structure self-documenting.

Migration and Operational Considerations

A robust methodology for frontend architecture is practical only if it supports real projects with legacy constraints. Recoil can be adopted incrementally, and FSD helps you do it without chaos.

Incremental migration strategy (store → atoms)

A pragmatic path that works well in production:

-

Pick one slice with clear boundaries

- Example:

features/theme-switcherorfeatures/catalog-filters

- Example:

-

Model a small atom

- Replace local state lifting and/or store reads for that feature

-

Introduce selectors for computed values

- Move derived logic out of components

-

Bridge old and new where needed

- If the old store must remain, create adapter functions or transitional hooks inside the slice

-

Codify import rules

- Enforce slice public APIs to prevent backsliding into global coupling

-

Repeat slice-by-slice

- Over time, the monolith store becomes thinner and more intentional

This approach keeps risk low and makes progress visible.

Testing: keeping confidence high

Recoil’s atomic model can be tested effectively when state is isolated:

- Test selectors as pure computations by setting atom values in a controlled environment

- Keep side effects in explicit modules (e.g.,

shared/api) - Prefer deterministic dependencies (avoid hidden time-based recomputation)

A positive pattern is to treat selectors as “read models” that can be validated independently from UI.

Performance and debugging considerations

Atomic state management can improve performance because subscriptions are fine-grained. Still, good hygiene matters:

- Avoid unnecessary atom churn (don’t store large frequently-changing objects if only a field is needed)

- Prefer stable data shapes

- Use selectors to normalize and derive data close to consumption

- Keep write paths explicit to simplify debugging

If you track architecture health, consider illustrative metrics like:

- Mean time to implement a scoped change in one feature (goal: trending down)

- Number of cross-slice imports per feature (goal: stable and intentional)

- Onboarding time for new engineers to deliver a first PR (goal: predictable)

These are not universal numbers, but they are practical indicators of improved modularity.

Common pitfalls (and how FSD prevents them)

Pitfall: “Global atoms” that everyone edits

- FSD solution: move ownership to the responsible slice; expose only needed setters

Pitfall: Derived state duplicated in UI

- Recoil solution: move it into selectors; keep components thin

Pitfall: Cross-feature imports that create dependency cycles

- FSD solution: strict layer rules and slice public APIs reduce accidental cycles

Pitfall: Async scattered everywhere

- Recoil solution: centralize async orchestration in selector families (or use a server-state library and bridge)

The combined approach creates a calm, predictable development environment—especially valuable for teams with multiple squads contributing to one frontend.

Conclusion

Recoil’s atomic model replaces the “one store to rule them all” mindset with a composable dependency graph of atoms and selectors, which makes shared state more modular, readable, and performance-friendly. When you add async selectors and parameterized families, you gain a clear way to model distributed UI state and derived read models without bloating components. Pairing this with Feature-Sliced Design turns those technical benefits into an architectural advantage: ownership becomes explicit, public APIs reduce coupling, and refactoring becomes safer over time. Adopting a structured methodology like FSD is a long-term investment in code quality, onboarding speed, and team productivity.

Ready to build scalable and maintainable frontend projects? Dive into the official Feature-Sliced Design Documentation to get started.

Have questions or want to share your experience? Visit our homepage to learn more!