The Case for a Reactive MobX Architecture

TLDR:

MobX makes React apps fast and expressive through observable state and dependency-tracked updates, but large codebases can drift into store sprawl and implicit coupling. This article explains MobX reactivity, practical MobX + React patterns, and how Feature-Sliced Design introduces clear boundaries, public APIs, and slice ownership to keep reactive state scalable.

MobX can make UI state feel effortless—until the codebase grows and the “reactive graph” becomes hard to reason about. With observable state, computed values, and actions, MobX delivers fine-grained reactivity that pairs naturally with React, but it also demands clear boundaries. Feature-Sliced Design (FSD) on feature-sliced.design provides those boundaries, helping teams keep MobX stores cohesive, predictable, and scalable.

Key takeaways:

• MobX’s strength is transparent dependency tracking that updates only what actually changed.

• The scaling risk is not MobX itself; it’s implicit coupling and “store sprawl” without architecture.

• A reactive MobX architecture becomes reliable when you enforce ownership, public APIs, and isolation.

• Feature-Sliced Design turns these principles into a repeatable project structure for large teams.

Table of contents

• How MobX fine-grained reactivity really works

• MobX + React: efficient rerenders without constant memoization

• Structuring MobX stores in large applications

• MobX vs Redux: the architectural trade-offs

• Why architecture matters more with MobX: coupling, cohesion, and APIs

• Feature-Sliced Design as a reactive MobX architecture

• Blueprint: building a scalable MobX + React app with FSD

• Debugging, testing, and performance guardrails

• Migration notes: adopting MobX and FSD incrementally

• Conclusion

How MobX fine-grained reactivity really works

When developers search for “mobx” they’re usually looking for clarity: What is MobX actually doing under the hood, and why does it feel so fast? The answer is a small set of ideas executed consistently: observable state, computed derivations, actions, and reactions. Together they form a reactive dependency graph that updates precisely and predictably—when you design the boundaries right.

The core idea: track reads, re-run dependents

MobX builds a runtime dependency graph:

• When a computation runs (a computed getter or an observer component render), MobX records which observables were read.

• Those reads become dependencies.

• When any dependency changes, MobX marks the computation as stale and re-runs it when needed.

This is why MobX is often described as “transparent” reactivity: you don’t wire subscriptions manually; you just read state, and MobX does the tracking.

Diagram description (mental model):

Imagine a graph with three kinds of nodes:

• Observables (raw state)

• Computeds (derived state)

• Observer renders (UI reads)

Edges connect “reads”:

Observable → Computed → Observer render

When an action mutates an observable, MobX invalidates the minimal set of computeds and observer renders that depended on it. That’s fine-grained reactivity: updates are targeted by dependency, not by broad “store changed” events.

Observable state: what should be observable (and what shouldn’t)

Observable state works best when it represents facts:

• domain facts (entities, aggregates, invariants)

• UI session facts (selected id, open/closed, in-progress form values)

• request status (idle/loading/success/error)

It works worse when it represents derived facts or “computed-but-stored” values, like:

• totals that can be derived from items

• filtered lists that can be derived from filters + items

• flags that duplicate other flags

A reliable MobX architecture keeps the source of truth minimal and uses computed values for derivations. This increases cohesion and reduces the chance of state drifting out of sync.

Computed values: cached derivations that raise cohesion

Computed values are not just convenience getters. They’re architecture:

• They centralize business logic near the state it derives from.

• They cache results until dependencies change.

• They prevent repeated work during rerenders and interactions.

In large React applications, computed values often become the difference between a UI that feels “instant” and one that slowly accumulates micro-lag.

Example (conceptual pseudo-code):

class CartStore {

items = [] // observable array

constructor() { makeAutoObservable(this) }

get totalPrice() {

return this.items.reduce((sum, it) => sum + it.price * it.qty, 0)

}

get badgeCount() {

return this.items.reduce((sum, it) => sum + it.qty, 0)

}

}

A subtle but important point: computed values are most effective when they stay pure (no side effects), and when they return stable shapes when possible (or at least are used intentionally by the UI).

Actions: mutation with intent, not chaos

MobX allows mutable state, and that’s not inherently risky. The risk comes from unconstrained mutation.

A practical rule for large teams:

• Treat actions as the only place where observable state changes.

• Treat action names as “business intent,” not implementation detail.

Good action naming looks like:

• applyCoupon(code)

• setShippingMethod(method)

• addItem(productId, qty)

• confirmEmail(token)

This creates a system where changes are explainable: “The UI called addItem; the cart updated; the badge rerendered.”

Many MobX teams also enforce action discipline with configuration so accidental writes outside actions are easier to catch early in development.

Reactions: side effects that belong to a boundary

MobX reactions (reaction, autorun, when) are where you wire side effects:

• persistence (save draft to storage)

• analytics (track significant state transitions)

• network synchronization (refetch on condition change)

• navigation triggers (redirect on auth state changes)

A reliable reactive architecture keeps reactions:

• close to the slice that owns the behavior

• explicit and easy to discover

• limited in scope (avoid “global magic”)

A common anti-pattern is a global “effects.ts” file with dozens of reactions referencing everything. It’s hard to maintain because it violates ownership: nobody knows which feature truly owns the effect.

Why MobX feels “less boilerplate” than many alternatives

MobX often requires less glue than event-based state management because:

• Reactivity is based on reads, not on manually written selectors everywhere.

• Derived state is modeled as computed values, not duplicated snapshots.

• UI updates “just happen” through observer tracking.

That ergonomics is a genuine advantage—especially when teams protect it with a clear structure like Feature-Sliced Design.

MobX + React: efficient rerenders without constant memoization

The search intent behind “mobx react” is usually performance plus sanity: How do I get fast updates without turning my code into memoization puzzles? The MobX + React story is strong because of one simple rule:

Observer components rerender when the observables they read change.

The baseline integration: observer components

In a typical setup, you wrap reactive components with observer (commonly via mobx-react-lite). During render, MobX tracks observable reads.

Conceptual example:

const CartTotal = observer(({ cart }) => {

return <div>Total: {cart.totalPrice}</div>

})

If totalPrice changes, CartTotal rerenders. If it doesn’t, it won’t. No manual subscription logic. No selector equality tuning just to be “mostly correct.”

Designing rerender boundaries: small observers win

A practical performance pattern:

• Make observer components small and close to where data is displayed.

• Keep layout components mostly non-reactive.

• Avoid “one giant observer page” that reads half the app.

This creates predictable update scope. It also improves local reasoning: if a component rerenders, it’s because it read something reactive.

Avoiding accidental over-tracking

MobX’s dependency tracking is powerful, but it’s also honest: it tracks what you actually read. Some reads are accidental.

Common accidental reads:

• reading an entire store object instead of specific fields

• logging or stringifying observable objects inside render

• creating derived arrays/objects in render (causing churn)

A reliable MobX + React setup follows two habits:

-

Read what you need, not what you have.

• Preferstore.userNameoverstore.user.

• Preferstore.visibleItemsoverstore.items.filter(...)in render. -

Move derivations into computed values.

• It improves performance and keeps UI simple.

React hooks and MobX: a clean split of responsibilities

A healthy pattern is:

• React hooks manage component lifecycle and non-reactive concerns.

• MobX stores manage reactive state and derivations.

For example:

• Use a hook to create a store instance for a widget scope.

• Use MobX to model the widget state and computed derivations.

• Use observer components to render.

This balance avoids mixing side effects into reactive derivations, which keeps behavior easier to test and reason about.

UI state vs domain state: don’t over-centralize

Not all state should live in global MobX stores. A pragmatic split:

• Entity/domain state: long-lived, shared, invariant-driven (belongs in entities).

• Feature workflow state: tied to a user action flow (belongs in features).

• Widget composition state: UI coordination for a block (belongs in widgets).

• Truly local state: stays in component state.

This is not dogma; it’s a scaling strategy. Over-centralization makes reactive graphs too interconnected, increasing coupling and making refactors risky.

Structuring MobX stores in large applications

If MobX is so ergonomic, why do some large MobX codebases become hard to maintain?

Because flexibility without conventions tends to produce:

• god stores

• circular dependencies

• “any slice can mutate any state”

• unclear ownership of async flows and side effects

A robust MobX architecture needs structure that protects modularity.

What “good structure” means in software engineering terms

You want:

• High cohesion: related logic stays together (store + derivations + actions).

• Low coupling: modules interact through stable contracts, not internals.

• Explicit public API: consumers import from index.ts, not deep paths.

• Isolation: internal details can change without breaking unrelated code.

These principles translate well to frontend state management, and they become critical when your React app grows across teams and domains.

Store pattern 1: entity stores as domain modules

Entity stores represent domain concepts (User, Cart, Product). They usually contain:

• observable state of the entity set / aggregate

• computed derivations (selectors)

• actions that enforce invariants

Example structure:

src/ entities/ cart/ model/ cart.store.ts types.ts selectors.ts ui/ cart-badge.tsx index.ts

The critical piece is index.ts as a public API. Consumers should import from entities/cart, not from entities/cart/model/cart.store.ts.

That’s not cosmetic. It’s an architectural boundary: it prevents accidental coupling to internals and supports safe refactoring.

Store pattern 2: feature models as use-cases and workflows

Features represent user intentions (Login, AddToCart, ApplyCoupon). Feature models often coordinate:

• calling entity actions

• validation

• async flows (loading/error handling)

• integration boundaries (analytics, navigation triggers)

Example structure:

src/ features/ add-to-cart/ model/ add-to-cart.model.ts ui/ add-to-cart-button.tsx index.ts

A clean rule:

• entities hold durable state and invariants

• features orchestrate changes across entities

• widgets/pages compose UI and call feature APIs

This keeps responsibilities clear and reduces “smart components” that do everything.

Store pattern 3: composition root and dependency injection

Cross-store references can create hidden cycles if every store imports every other store. Instead:

• Construct stores in one place (composition root).

• Pass dependencies explicitly (constructor params or factory args).

• Expose only what consumers need.

Conceptual example:

function createStores(deps) {

const cart = new CartStore()

const user = new UserStore(deps.api)

const addToCart = new AddToCartModel({ cart, user, api: deps.api })

return { cart, user, addToCart }

}

This gives you:

• clearer dependency direction

• easier testing (swap deps)

• fewer cycles

It’s a lightweight version of “ports and adapters” that works well in frontend systems.

Store pattern 4: stable read interfaces (computed selectors)

In large UIs, the biggest performance and correctness wins often come from one habit:

The UI reads computed selectors, not raw internal arrays.

Instead of:

• store.items.filter(...).map(...) in many components

Prefer:

• store.visibleItems

• store.sortedItems

• store.canCheckout

This consolidates business rules and creates a single “source of truth” for how the UI should interpret state.

MobX vs Redux: the architectural trade-offs

The MobX vs Redux question is not a popularity contest. It’s a design decision about how your system should evolve.

The most important split:

• MobX is reactive and mutable-by-default (with optional enforcement).

• Redux is event-driven and immutable-by-default (with ergonomic helpers).

A practical comparison table

| Dimension | MobX | Redux Toolkit (typical) |

|---|---|---|

| Update model | Actions mutate observable state (mutable semantics) | Reducers produce next state (immutability semantics) |

| UI updates | Fine-grained dependency tracking (reads drive subscriptions) | Selector subscriptions + equality checks |

| Derived state | Computed values (cached, reactive) | Memoized selectors (explicit) |

| Boilerplate | Lower, especially for complex derivations | Medium, but consistent across teams |

| Debug story | Track dependencies and action calls | Strong action log and tooling ecosystem |

When MobX is a strong fit

MobX often shines when your product has:

• dense interactive UI (editors, builders, dashboards)

• heavy derived state (filters, computed summaries, permissions)

• performance sensitivity (large lists, frequent updates)

• a need for “local” stores that still compose cleanly

• teams comfortable enforcing architectural boundaries

MobX’s fine-grained reactivity can reduce the need for constant manual memoization and reduce rerender blast radius—when the structure is sound.

When Redux (or similar) may be more comfortable

Redux can be a good fit when you want:

• strict, explicit state transitions

• a consistent event log for debugging and auditing

• onboarding via a single global convention

• heavy reliance on middleware patterns and standardized workflows

Many teams prefer the explicitness of reducers and action logs. That preference is valid—especially in environments where consistency across many contributors is the top priority.

A balanced conclusion for architects

There’s no universal winner. But there is a reliable pattern:

MobX becomes a great long-term choice when paired with a structure that makes ownership and boundaries explicit.

That’s exactly the gap Feature-Sliced Design is designed to fill.

Why architecture matters more with MobX: coupling, cohesion, and APIs

MobX reduces friction. Reduced friction is great—until it enables shortcuts that turn into permanent coupling.

The scaling problems most MobX teams face are not “MobX problems.” They’re boundary problems.

The hidden risk: implicit coupling through shared reactive objects

In a loosely structured MobX app, it’s easy for components and stores to:

• import deep internal modules

• mutate fields directly

• read large observable objects

• add reactions that depend on “everything”

Over time, the reactive graph becomes hard to predict. A small change causes surprising UI updates or side effects.

This is classic software architecture behavior:

• low isolation → higher change cost

• higher coupling → brittle refactors

• unclear ownership → slower onboarding

The fix: enforce ownership of state changes

Ownership answers:

• Who is allowed to mutate this state?

• Where do invariants live?

• Which module is responsible when behavior changes?

In practice:

• Entity stores own domain invariants.

• Feature models own workflows and orchestration.

• UI reads state but does not freely mutate it.

This is not bureaucracy. It’s how you keep velocity high when the team scales.

Public API as a refactoring tool

Public APIs are a stability layer:

• they reduce dependency surface area

• they allow internal reorganizations without mass edits

• they improve discoverability (“import from slice root”)

If you’ve ever tried to refactor a large React codebase with deep import chains, you’ve felt this pain directly. Public APIs are one of the simplest and most effective fixes.

A compact comparison of approaches that influence structure

| Approach | Strength in practice | Typical risk without discipline |

|---|---|---|

| MVC / MVP | Clear UI vs logic separation | Controllers/ViewModels become cross-feature “service layers” |

| Atomic Design | Excellent UI composition language | Domain logic leaks into UI layers; features blur |

| Domain-Driven Design (frontend) | Strong domain modeling | Hard to map to code without clear slicing rules |

| Feature-Sliced Design | Enforced boundaries via layers + slices + APIs | Requires consistent index exports and import discipline |

This is why many teams adopt FSD alongside state management: it creates a repeatable, reviewable architecture that resists entropy.

Feature-Sliced Design as a reactive MobX architecture

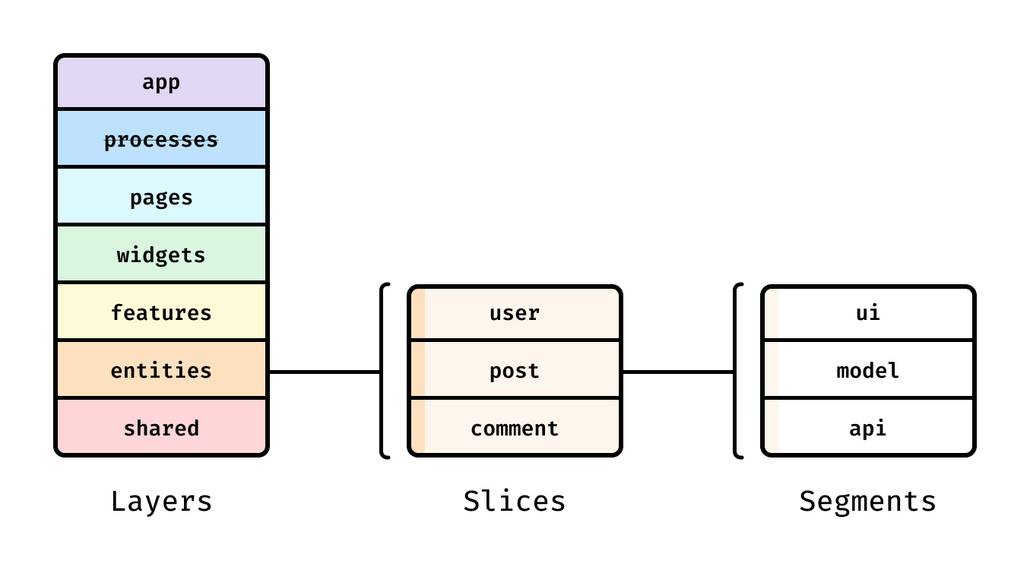

Feature-Sliced Design (FSD) is a methodology for structuring frontend projects around:

• layers (app/pages/widgets/features/entities/shared)

• slices (domain- or feature-aligned modules)

• segments (ui/model/lib/api)

• public APIs (index.ts) and import discipline

MobX integrates naturally into this because its primitives map cleanly to slice ownership.

How MobX maps to FSD layers

A pragmatic mapping:

• shared/

– utilities, base UI kit, shared API clients, generic helpers

• entities/

– MobX entity stores (domain state + invariants + computed selectors)

• features/

– MobX feature models (use-cases, flows, validation, orchestration)

• widgets/

– composite UI blocks; optional local stores for coordination

• pages/

– route-level composition and data wiring

• app/

– initialization, providers, composition root

This creates a clean dependency direction:

shared → entities → features → widgets → pages → app (composition)

In real projects, you may occasionally bend edges (for example, widgets often depend on entities and features), but the key is: avoid reverse dependencies that break isolation.

Public API discipline: “import from the slice root”

In an FSD + MobX project, enforce a simple rule:

• External consumers import from entities/cart or features/add-to-cart, not deep files.

Example exports:

// entities/cart/index.ts

export { CartStore } from "./model/cart.store"

export type { CartItem } from "./model/types"

export { CartBadge } from "./ui/cart-badge"

This reduces coupling and makes architectural decisions enforceable in code review.

Reactive ownership boundaries: keeping the state graph readable

Diagram description (what you want):

• Each slice is a cluster of observables + computed + actions.

• Most reactive links stay inside the cluster.

• Cross-slice links are few, intentional, and go through public APIs.

In other words:

• dense cohesion inside slices

• controlled coupling between slices

This is what prevents “reactive spaghetti” where any update can ripple unpredictably.

A practical “MobX + FSD” anti-pattern table

| Problem | Anti-pattern | Better pattern (FSD-friendly) |

|---|---|---|

| Store sprawl | One global RootStore with every concern | Separate entity + feature stores wired in app composition |

| Hidden coupling | Components mutate observables directly | Components call feature/entity actions (intent methods) |

| Refactor pain | Deep imports into model/internal/* | Slice public API via index.ts exports |

This table is useful in code review: it turns architecture into concrete, observable decisions.

Blueprint: building a scalable MobX + React app with FSD

This section is a practical, step-by-step implementation shape you can apply to a new project or a refactor.

Step 1: Identify your entities and model them first

Start with domain nouns:

• User

• Session

• Product

• Cart

• Order

For each entity, write down:

- the minimal observable state it must own

- computed selectors that the UI will need

- actions that represent valid domain transitions

Example (conceptual):

class ProductStore {

productsById = new Map()

isLoading = false

error = null

constructor(api) {

makeAutoObservable(this, {}, { autoBind: true })

this.api = api

}

get list() { return Array.from(this.productsById.values()) }

get isEmpty() { return this.productsById.size === 0 && !this.isLoading }

*load() {

this.isLoading = true

this.error = null

try {

const data = yield this.api.products.list()

data.forEach(p => this.productsById.set(p.id, p))

} catch (e) { this.error = e } finally { this.isLoading = false }

}

}

Notice what this does well:

• observable state is minimal

• derivations are computed

• mutations are inside methods

Step 2: Create feature models for workflows, not “more state”

A feature model should answer: What user action is this enabling?

Examples:

• Add to cart

• Apply coupon

• Checkout

• Login

• Change locale

A feature model usually depends on entity stores via public APIs:

class AddToCartModel {

constructor({ cart, products, analytics }) {

makeAutoObservable(this, {}, { autoBind: true })

this.cart = cart

this.products = products

this.analytics = analytics

}

add(productId, qty = 1) {

const product = this.products.getById(productId)

if (!product) return

this.cart.addItem({ id: product.id, price: product.price }, qty)

this.analytics.track("add_to_cart", { productId, qty })

}

}

This keeps orchestration logic out of UI components and prevents entity stores from becoming “everything stores.”

Step 3: Wire stores in app/ as a composition root

This is where you instantiate and connect stores:

// app/providers/create-stores.ts

function createStores() {

const api = createApiClient()

const analytics = createAnalytics()

const products = new ProductStore(api)

const cart = new CartStore()

const addToCart = new AddToCartModel({ cart, products, analytics })

return { api, analytics, products, cart, addToCart }

}

Then expose stores via a provider (React context is common):

// app/providers/store-provider.tsx (conceptual)

const StoresContext = createContext(null)

function StoreProvider({ children }) {

const stores = useMemo(() => createStores(), [])

return <StoresContext.Provider value={stores}>{children}</StoresContext.Provider>

}

This supports testing and keeps store construction centralized and discoverable.

Step 4: Keep observer boundaries close to data reads

In UI:

• use observer components to render derived state

• keep components small and composable

• move logic into computed selectors and feature actions

Example structure:

src/ widgets/ cart-panel/ ui/ cart-panel.tsx cart-items-list.tsx index.ts

A great pattern is:

• CartItemsList is observer and reads cart.visibleItems

• each row is observer and reads item.qty, item.price, etc.

This prevents a single update from rerendering the entire screen.

Step 5: Enforce import discipline with slice public APIs

In code review, watch for deep imports:

• entities/cart/model/cart.store.ts (avoid)

• entities/cart (preferred)

FSD makes it easy to enforce with conventions and tooling. The payoff is compounding: every refactor becomes cheaper.

Debugging, testing, and performance guardrails

MobX is pleasant when things are clear, and it’s still manageable when things go wrong—if you set guardrails.

Guardrail 1: enforce disciplined writes

Even if your project doesn’t require it, the team habit should be:

• all writes occur inside actions / store methods / feature commands

This provides:

• predictable mutation paths

• clearer code review

• easier debugging (“who changed this?”)

Guardrail 2: prefer computed selectors for expensive derivations

If you repeatedly compute:

• filtered lists

• sorted lists

• totals, counters, permissions matrices

Move them into computed selectors. This improves both:

• performance (cached derivations)

• correctness (single authoritative derivation)

Guardrail 3: test stores as plain objects

One of MobX’s practical benefits is testability: stores are plain JS/TS objects.

A store test can:

- create a store with fake dependencies

- call actions

- assert observable state and computed values

This style is fast, deterministic, and avoids rendering React just to test business logic.

Guardrail 4: performance profiling with a clear hypothesis

When performance matters, profile with intent:

• identify the slow screen

• find components rerendering unexpectedly

• check what observables they read

• shrink observer boundaries

• replace render-time derivations with computed values

This is a positive feedback loop: the more your architecture aligns with MobX’s strengths, the more you benefit from its fine-grained updates.

Guardrail 5: side effects should have a “home”

A simple ownership rule:

• If a side effect supports a feature workflow, it belongs in that feature model.

• If it supports an entity lifecycle, it belongs near the entity model.

• If it’s app-wide infrastructure, it belongs in app/ or shared/.

This reduces surprises and makes behavior easier to locate during incidents.

Migration notes: adopting MobX and FSD incrementally

Many teams are not starting from scratch. If you’re migrating from Redux, context-heavy state, or ad-hoc local state, you can still adopt MobX and Feature-Sliced Design pragmatically.

A low-risk migration path

-

Introduce FSD structure first (even with your existing state solution).

• separateentities/,features/,widgets/,pages/,shared/

• add public APIs (index.ts)

• reduce deep imports -

Move one cohesive domain area to MobX.

• pick a feature with clear ownership (e.g., Cart)

• create an entity store + computed selectors

• create a feature model for the workflow -

Wire the new store through the app composition root.

• keep boundaries explicit

• avoid mixing “old state writes” into new entity internals -

Expand slice by slice.

• migrate the next entity

• keep workflows in features

• gradually reduce legacy glue

This approach delivers value early (structure, public APIs, cohesion) and avoids big-bang rewrites.

A positive way to evaluate success

Track improvements that matter to teams:

• fewer “where does this logic live?” questions

• faster onboarding for new developers

• smaller PRs with clearer ownership

• fewer refactors that spill across the whole codebase

• better UI responsiveness under frequent updates

These are durable indicators that your architecture is working.

Conclusion

MobX offers an elegant model for reactive programming in frontend systems: observable state as the source of truth, computed values for cached derivations, and actions to express intent. In React, this translates into efficient updates through dependency tracking—often reducing rerender scope and boilerplate. The main risk is architectural: without boundaries, MobX flexibility can lead to implicit coupling and store sprawl. Feature-Sliced Design counters that with layers, slice ownership, and public APIs that keep your reactive graph understandable and refactors safe. Over time, this structure becomes a practical investment in code quality, onboarding speed, and sustainable delivery.

Ready to build scalable and maintainable frontend projects? Dive into the official Feature-Sliced Design Documentation to get started.

Have questions or want to share your experience? Visit our homepage to learn more!