Micro-Frontends: Are They Still Worth It in 2025?

TLDR:

Are micro-frontends still worth the complexity in 2025? This guide breaks down the main approaches—Module Federation, single-spa, qiankun, iframes, web components, and import maps—then shows how Feature-Sliced Design helps teams keep boundaries, public APIs, and performance under control as systems scale.

Micro-frontend architecture promised independent teams and independent deployments; in 2025 the real question is whether that promise reduces your total cost of change without breaking UX, performance, or governance. Feature-Sliced Design (FSD) from feature-sliced.design often delivers the same scalability benefits inside a single codebase, and it also makes “extracting a micro-frontend later” far safer.

Table of contents

- What a micro-frontend really is (and what it isn’t)

- Common implementation approaches in 2025

- Frameworks and platforms: Module Federation vs single-spa vs qiankun

- The real challenges: routing, state sharing, and deployments

- Decision guide: when micro-frontends are worth it

- Feature-Sliced Design as the internal architecture for MFEs

- Migration playbook: from monolith to micro-frontends with FSD

- FAQ: micro-frontends in 2025

- Conclusion

What a micro-frontend really is (and what it isn’t)

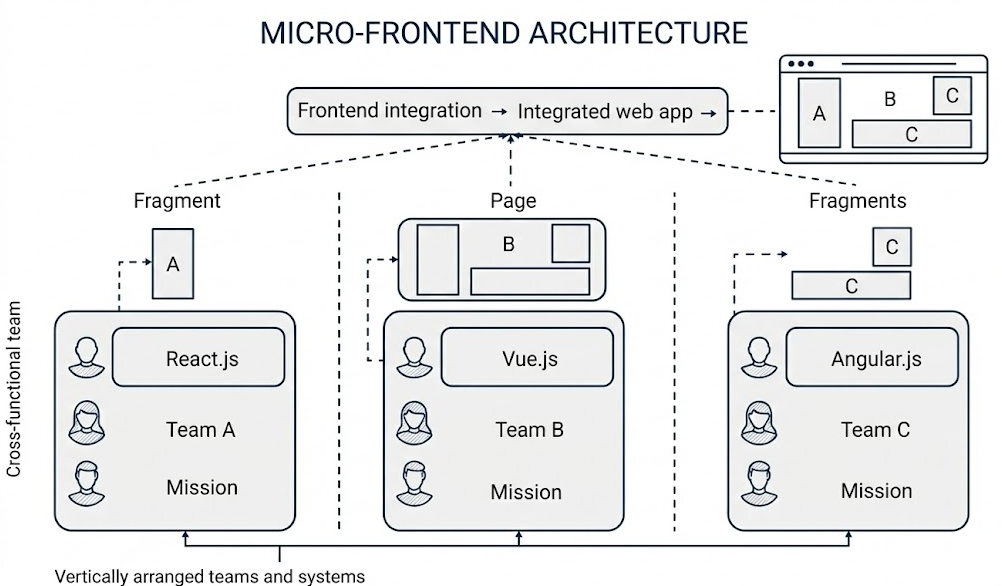

A key principle in software engineering is that architecture is the set of decisions that are expensive to change. Micro-frontends (MFEs) are such a decision: you’re choosing distributed ownership and independent delivery over the simplicity of “one deployable UI.”

In practical terms, a micro-frontend is:

- A product/domain slice of the UI (often a route subtree or a large widget) that can be built and released with meaningful independence.

- Integrated into a shell (host/container/root) via runtime composition or orchestration.

- Governed by explicit contracts: public API surfaces, routing boundaries, events, design tokens, and compatibility rules.

Single-spa describes MFEs as “sections of your UI” that can be managed by different teams and may use different frameworks.

What micro-frontends solve (when they work)

MFEs shine when the bottleneck is coordination (a common symptom in “frontend microservices” organizations):

- Team autonomy at scale: fewer merge conflicts, fewer “release trains,” clearer ownership.

- Independent deployment: a domain team can ship without waiting for unrelated changes.

- Gradual modernization: run legacy and new stacks side-by-side during migration (a core single-spa use case).

What micro-frontends do not automatically solve

MFEs don’t magically fix:

- spaghetti code inside each micro-app

- inconsistent patterns across teams

- coupling through shared dependencies and global state

- UX drift (layout, accessibility, design system inconsistency)

Without internal structure, you can end up with “many mini-monoliths.”

Common implementation approaches in 2025

Micro-frontends are less about “React vs Vue” and more about how you compose.

1) Module Federation (runtime module sharing)

Webpack 5’s ModuleFederationPlugin lets independent builds provide or consume modules at runtime. The host loads a remote manifest (often remoteEntry.js) and imports exposed modules (routes/components) on demand.

In 2025, “Module Federation” is also bigger than webpack: there are community docs and Vite-oriented plugins that aim to produce and consume federation-compatible artifacts. This matters if you’re standardizing on Vite for DX but still need federated deployment boundaries.

Pseudo-config (simplified):

// host/webpack.config.js

new ModuleFederationPlugin({

remotes: {

checkout: "checkout@https://cdn.example.com/checkout/remoteEntry.js",

},

shared: { react: { singleton: true }, "react-dom": { singleton: true } }

})

// checkout/webpack.config.js

new ModuleFederationPlugin({

name: "checkout",

filename: "remoteEntry.js",

exposes: { "./routes": "./src/routes" },

shared: { react: { singleton: true }, "react-dom": { singleton: true } }

})

Why teams pick it:

- independent deployment with “native-feeling” integration

- runtime composition without iframes

- potential dependency dedupe (when governance is strong)

2) single-spa (application orchestration)

single-spa is a framework for bringing together multiple JavaScript microfrontends in one application. It provides routing-based activation plus mount/unmount lifecycles.

Pseudo-registration:

registerApplication({

name: "@org/checkout",

app: () => System.import("@org/checkout"),

activeWhen: ["/checkout"]

});

3) qiankun (single-spa inspired, enterprise runtime)

qiankun is inspired by and based on single-spa, and emphasizes production features like style isolation and JS sandboxing.

4) Iframes (document-level isolation)

Iframes still matter when you need strong isolation or security boundaries. The sandbox attribute and CSP sandboxing are key tools for restricting embedded content.

The trade-off is heavier UX seams and cross-app communication friction.

5) Web Components (custom elements + Shadow DOM)

Web Components can ship UI as framework-agnostic custom elements; Shadow DOM provides encapsulation against accidental CSS/DOM interference.

They work best for leaf widgets, not whole routed domains.

6) Composable frontend with native ESM + import maps

A “composable frontend” variant uses browser-native modules plus <script type="importmap"> to control specifier resolution.

Import maps have very high global support (Can I use reports ~94.5% usage as of October 2025).

Pseudo-setup:

<script type="importmap">

{ "imports": { "@org/checkout": "https://cdn.example.com/checkout/v42/entry.js" } }

</script>

<script type="module">

const { mountCheckout } = await import("@org/checkout");

mountCheckout(document.querySelector("#slot"), { locale: "en" });

</script>

This reduces bundler lock-in, but you own more of the governance (versions, performance, security).

Comparison table: approaches at a glance

| Approach | Where it shines | Typical trade-offs |

|---|---|---|

| Module Federation | Runtime composition + shared deps | Version skew, caching, shared library governance |

| single-spa / qiankun | Orchestration + multi-framework migration | Extra runtime layer; still need strict contracts |

| Iframes / Web Components / import maps | Isolation (iframes), encapsulation (WC), platform-native loading (import maps) | UX seams, theming/testing complexity, DIY governance |

Frameworks and platforms: Module Federation vs single-spa vs qiankun

Start with: what boundary do you need? The boundary determines the tool.

Boundary types

• Runtime module boundary (Module Federation, import maps)

Expose modules; shell imports them at runtime.

• Lifecycle/app boundary (single-spa, qiankun)

Expose an application with mount/unmount lifecycles.

• Document boundary (iframe)

Strong isolation, heavier integration cost.

Where teams get burned (and how to avoid it)

-

Implicit coupling through deep imports

“Just import that internal file” becomes a hidden API. Fix: define public APIs and forbid deep imports. -

Version wars in shared deps

Two React versions or incompatible routers can break runtime invariants. Fix: a “shared kernel” policy (singletons, upgrade cadence, compatibility checks). -

The “orchestrator is the architecture” fallacy

single-spa/qiankun are orchestration, not internal modularity. You still need code organization and boundaries inside each micro-app.

Leading architects suggest choosing the simplest boundary that satisfies your constraints, then investing in contracts and governance.

A pragmatic selection heuristic:

- Need hard isolation → iframe.

- Need multi-framework migration → single-spa/qiankun.

- Need shared runtime + independent deploy → Module Federation.

- Want platform-native composition → import maps (with strong governance).

The real challenges: routing, state sharing, and deployments

Micro-frontends succeed when cross-team interfaces are boring.

1) Routing that stays predictable

Treat the URL as a contract.

Recommended model:

- Shell owns top-level routes.

- Each MFE owns a route subtree (

/checkout/*,/profile/*) and its internal router under that prefix.

Diagram (conceptual): Shell Router → loads Checkout Remote → Checkout Router renders /checkout/*.

Avoid “route weaving” (multiple MFEs must coordinate to render one page). It’s a sign your domain boundaries are wrong.

2) State sharing without recreating a monolith

The fastest way to lose autonomy is a shared global store where everyone writes.

Prefer:

- Local state inside the owning MFE

- URL as shared state for filters/tabs/IDs

- Event-driven integration for cross-domain coordination

- Backend as source of truth (BFF patterns often reduce frontend coupling)

Pseudo-pattern: typed event bus

export type AppEvent =

| { type: "checkout/finished"; orderId: string }

| { type: "auth/loggedIn"; userId: string };

const handlers = new Set<(e: AppEvent) => void>();

export const emit = (e: AppEvent) => handlers.forEach(h => h(e));

export const on = (h: (e: AppEvent) => void) => (handlers.add(h), () => handlers.delete(h));

A practical rule: share signals, not structures. If two MFEs must “share a data model,” prefer a stable API contract (or events) over a shared in-memory object graph.

| State-sharing pattern | Good for | Watch-outs |

|---|---|---|

| URL as state | Filters, pagination, selected IDs | Requires careful backwards compatibility; avoid leaking internal params |

| Typed events | Cross-domain coordination (auth, checkout completion) | Event taxonomy needs ownership; avoid “god events” |

| Backend/BFF as source of truth | Consistency across MFEs and devices | Adds backend work; requires observability and caching strategy |

3) Performance: avoid the “remote entry waterfall”

Micro-frontends can improve performance (independent code splitting), but only if you prevent a runtime waterfall:

- Shell loads → discovers remotes → fetches

remoteEntry→ fetches chunks → finally renders. - Each extra hop delays LCP and increases failure modes.

Mitigations that work well in 2025:

-

Route-level prefetching

Prefetch the remote entry and critical chunks when the user is likely to navigate (hover intent, “next step” in a funnel). -

Performance budgets per MFE

Treat each micro-app like a product: set budgets for bundle size, LCP contribution, and interaction latency (INP). -

Share only what must be shared

A singleton React is great, but over-sharing large libraries can create upgrade lockstep. Aim for a small shared kernel and let everything else duplicate if it’s cheaper. -

CSS and design tokens discipline

Most UX seams come from late-loading styles. Prefer a design system with stable tokens and predictable global styles, and keep “page critical CSS” close to the owning route.

4) Local development and CI/CD: the hidden tax

MFE programs often stall on day-to-day DX:

- “How do I run Checkout locally against a remote Profile?”

- “Which remote version is this environment using?”

- “Why did this build pass but production breaks?”

Practical patterns:

• Remote overrides: allow developers to point the shell to localhost for one MFE while consuming others from a dev CDN.

• Contract tests: validate the remote public API against the shell during CI (type checks + smoke mount).

• Integration environments: a nightly “full mesh” environment catches version skew before users do.

5) Dependency sharing without breaking hooks

With federation-style setups, shared deps are powerful and risky. Keep it stable by:

- Declaring a shared kernel (React, router, i18n, design tokens).

- Pinning or range-limiting versions with a published policy.

- Validating at runtime (shell rejects incompatible remotes).

- Enforcing via CI.

6) Independent deployments without production roulette

With N MFEs you run N versions at once, and compatibility combinations grow quickly (roughly N·(N−1)/2).

Practical safeguards:

- Contract-first remote entry points (one stable import surface).

- Semantic versioning for the public API.

- Canary + rollback by switching remote URLs.

- Cache discipline (version-pinned remoteEntry, immutable assets).

7) Design system and platform consistency

If teams don’t share a design system and a platform layer (telemetry, i18n, auth), the UI will fragment. FSD is often used as a foundation for controlled reuse and stable layering in such ecosystems.

Decision guide: when micro-frontends are worth it

In 2025, MFEs are worth it when the primary constraint is organizational scale.

Micro-frontends are usually worth it when…

• Many teams ship independently (weekly/daily).

• Domains are loosely coupled (Billing vs Catalog vs Support).

• You can invest in platform ownership (even a small “platform squad”).

• You’re mid-migration and need multiple frameworks to coexist.

Micro-frontends are usually not worth it when…

• You have 1–2 teams and the bottleneck is technical debt inside one repo.

• Most pages require tight cross-feature interaction.

• You can’t standardize UX/platform concerns.

In those cases, improving the monolith’s architecture (boundaries, public APIs, domain slices) usually yields higher ROI.

Micro-frontend vs monolith: measure the cost of boundaries

A useful way to compare a micro-frontend architecture to a modular monolith is to score boundary cost:

- Change lead time: does splitting reduce PR/release coordination, or does it increase integration work?

- Rollback safety: can you revert one domain quickly, or do you still need a full “product rollback”?

- Local development: can a developer run the whole product easily, or do they need a mini-platform just to start?

- Runtime performance: did you eliminate unused code, or create more network hops and duplicated bundles?

- Cross-cutting concerns: auth, i18n, analytics—are they consistent, or fragmented across repos?

If “boundary cost” is high, start with a monolith structured by Feature-Sliced Design and revisit MFEs once domains and contracts are clearer.

A lightweight decision matrix

| Situation | Best starting point | Why it works |

|---|---|---|

| 1–2 teams, codebase growing | Monolith + FSD | Keeps cohesion while enforcing boundaries and predictable structure |

| Many teams, shared product | MFE + platform + FSD inside MFEs | Preserves autonomy without sacrificing maintainability |

| Legacy modernization | single-spa/qiankun + FSD adoption | Enables incremental migration with lifecycle orchestration |

Feature-Sliced Design as the internal architecture for MFEs

Micro-frontends answer “how do we deploy independently?” Feature-Sliced Design answers “how do we keep code understandable and refactorable for years?”

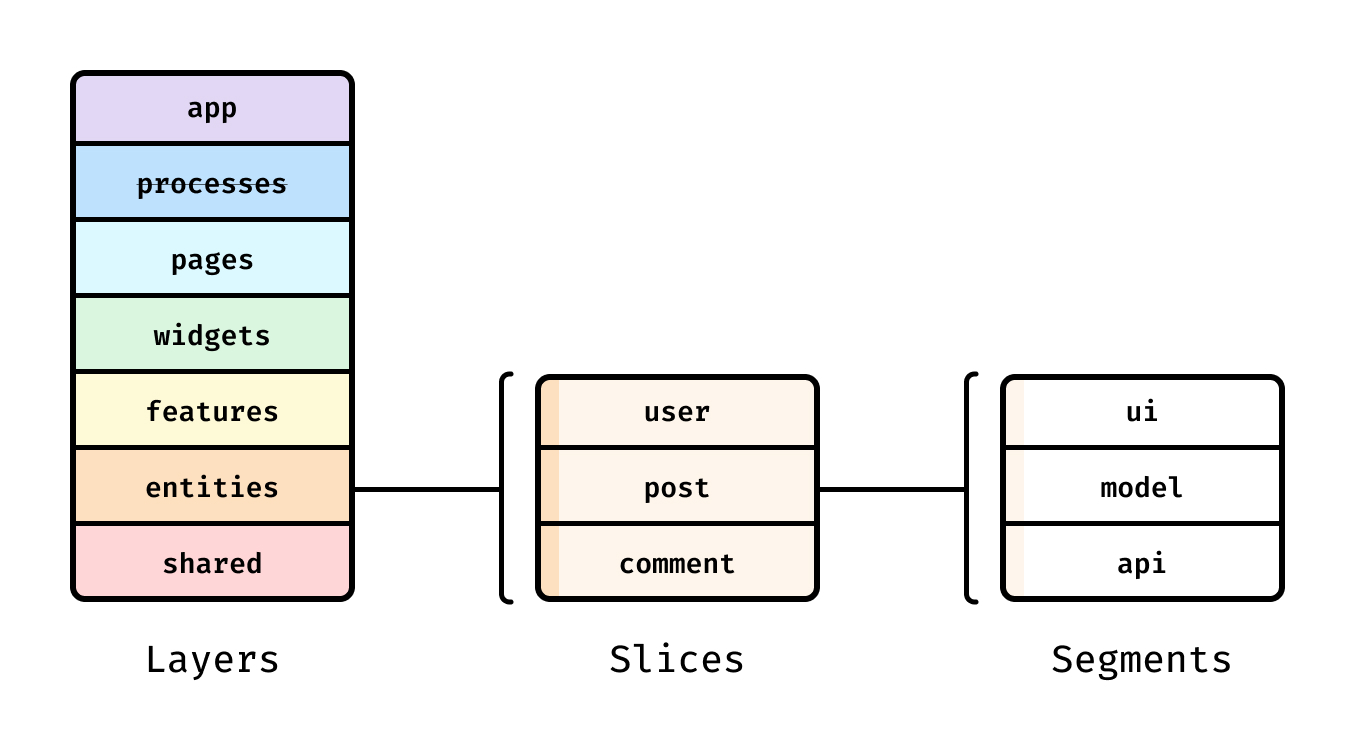

FSD organizes code by:

- Layers (responsibility and dependency direction)

- Slices (business/domain meaning, similar in spirit to DDD bounded contexts)

- Segments (technical purpose within a slice)

In practice, this pushes teams toward high cohesion within slices and low coupling across them—improving modularity without requiring distributed deployment.

The critical rule: public API gates

FSD’s “public API” is a contract and a gate: consumers import from the slice root (re-exports), not internal files.

Example:

// features/checkout/index.ts (public API)

export { CheckoutPage } from "./ui/CheckoutPage";

export { mountCheckout } from "./entry/mount";

export type { CheckoutMountProps } from "./model/types";

This is exactly the discipline micro-frontends need to avoid hidden coupling.

Comparing internal approaches (and why FSD complements MFEs)

| Methodology | What it optimizes | Typical gap in large products |

|---|---|---|

| MVC / MVP | Technical separation | Business boundaries blur; cross-feature coupling grows |

| Atomic Design | UI composition | Great for design systems, weak for domain logic organization |

| Feature-Sliced Design | Domain-driven modularity + strict dependencies | Requires learning boundaries; needs governance |

What FSD looks like inside one micro-frontend

src/

app/

pages/checkout/

widgets/orderSummary/

features/applyCoupon/

entities/order/

shared/ui/

shared/api/

As demonstrated by projects using FSD, a consistent layer/slice model reduces spaghetti code and speeds onboarding through predictability.

Migration playbook: from monolith to micro-frontends with FSD

Micro-frontends are easiest when treated as extraction, not greenfield.

FSD helps extraction by creating clear seams and stable APIs; the docs emphasize incremental migration and practical rules (including merging overly fine slices).

Step 1: Stabilize boundaries in the monolith

- Introduce layers/slices and a minimal “map” of domains.

- Add public APIs for cross-domain usage.

- Enforce import rules via linting/CI.

Step 2: Pick the right first extraction

Good first MFEs are usually:

- a route subtree with clear ownership (

/checkout/*) - a high-value domain with its own release cadence

- a capability you want to modernize independently

Avoid extracting tiny one-page features early.

Step 3: Define a real contract

For each remote:

- one entry module (

mount,routes, orwidget) - typed input props and emitted events

- version policy and compatibility checks

Pseudo-contract:

export type CheckoutMountProps = {

userId: string;

locale: string;

onEvent: (e: { type: "checkout/finished"; orderId: string }) => void;

};

export function mountCheckout(el: HTMLElement, props: CheckoutMountProps) {

// render app

}

Step 4: Build the platform “golden path”

Standardize the boring stuff:

- auth/session integration

- design system + tokens

- telemetry/error reporting

- local dev composition (shell + selected MFEs)

FAQ: micro-frontends in 2025

Are micro-frontends “dead” in 2025?

No. They’re mature. Teams evaluate MFEs on maintainability, performance, and governance—not novelty.

Is Module Federation still a strong default?

Yes for “shared runtime + independent deploy” setups, especially in webpack ecosystems. But it’s not a substitute for contracts and internal architecture.

What’s the safest way to start?

Adopt Feature-Sliced Design first. It improves modularity in a monolith and creates clean seams if you later extract MFEs.

Conclusion

Frontend decoupling is not an optional optimization. It is a fundamental requirement for building flexible, maintainable, and scalable web applications. By separating UI from business logic, adopting event-driven communication where appropriate, abstracting external services, and designing for reuse, teams can dramatically reduce technical debt and increase development velocity.

Adopting a structured architecture like Feature-Sliced Design is a long-term investment in code quality and team productivity. It provides a clear mental model for organizing complexity and evolving systems with confidence.

Ready to build scalable and maintainable frontend projects? Dive into the official Feature-Sliced Design Documentation to get started.

Have questions or want to share your experience? Visit feature-sliced.design to learn more!

Disclaimer: The architectural patterns discussed in this article are based on the Feature-Sliced Design methodology. For detailed implementation guides and the latest updates, please refer to the official documentation.