Modern Redux Architecture with Redux Toolkit

TLDR:

Redux still shines when shared state, async complexity, and team scale collide. This guide shows how Redux Toolkit and React Redux work together with Feature-Sliced Design to keep slices cohesive, selectors stable, and async logic disciplined—without the boilerplate.

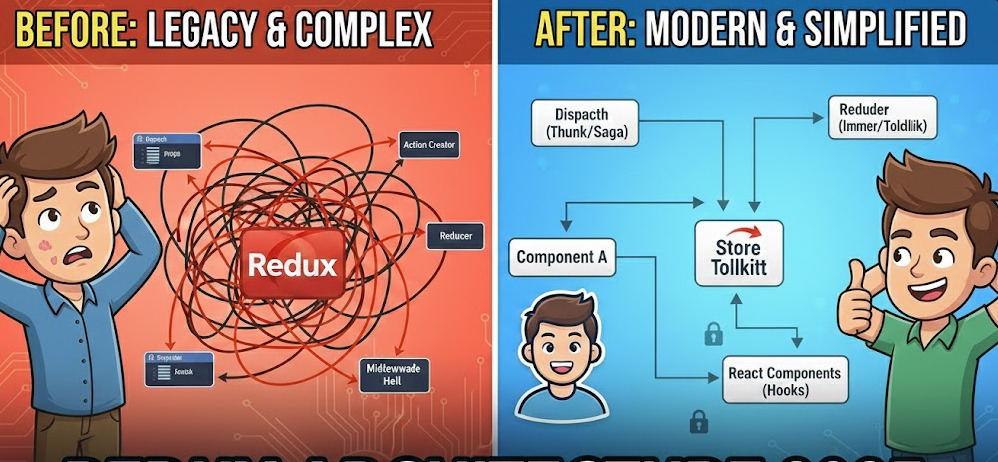

Redux has survived multiple “state management eras” in React because it solves a real scaling problem: coordinating complex, shared application state without turning your codebase into spaghetti. With Redux Toolkit, React Redux, and modern architectural methods like Feature-Sliced Design (FSD) from feature-sliced.design, you can keep Redux both productive for small teams and predictable for large ones—without the boilerplate that gave it a bad reputation.

Why Redux Toolkit is the modern default for Redux in React

A key principle in software engineering is to optimize for correctness under change. Redux’s core value is not “global state.” It’s a constrained, testable, observable state transition model that remains stable as teams grow.

The real problem Redux solves

In mid-to-large applications, the challenges tend to cluster around:

- Cross-feature coordination: multiple UI areas depend on the same domain facts (user session, permissions, cart totals, feature flags).

- Asynchronous complexity: caching, invalidation, retries, optimistic updates, request deduplication, cancellation.

- Debugging under pressure: reproducing bugs that require a specific sequence of events across components and screens.

- Onboarding and refactoring: new developers need to know “where to put things” and “what’s safe to change.”

Redux addresses these by enforcing a few constraints:

- State is centralized in a store (or a small number of stores).

- Updates happen through explicit events (actions).

- State transitions are pure (reducers), so they are deterministic and testable.

- Side effects are isolated (middleware), so async logic doesn’t leak into UI code.

Why Redux Toolkit changes the architecture conversation

Modern Redux is, in practice, Redux Toolkit-first:

- Opinionated defaults reduce configuration mistakes (DevTools, good middleware defaults).

- createSlice eliminates most action-type boilerplate and aligns code around “a feature slice of state.”

- Immer-based immutable updates allow reducer code to read like mutation while keeping immutability guarantees.

- RTK Query (optional but powerful) provides a strong default for data fetching, caching, and invalidation.

The result is a “batteries-included” state container that supports a clean architecture—if you structure it intentionally.

A mental model for modern Redux data flow

When people say Redux is “complicated,” they often mean they don’t see the boundaries. Use this simple schema:

UI (components) -> dispatch(action) -> middleware (async, logging, analytics, API calls) -> reducer (pure transition) -> store (new state) -> selectors (read model) -> UI re-renders

The architecture goal is to keep each arrow narrow and predictable, reducing coupling and increasing cohesion.

Redux fundamentals without the fluff: actions, reducers, store, and selectors

To build a scalable Redux architecture, you need a shared understanding of the primitives—especially how they map to modular design.

Store: the runtime container for state and behavior

In Redux Toolkit, the store is typically created with configureStore. In architectural terms, the store is the composition root for state-related concerns:

- root reducer composition

- middleware composition

- DevTools toggles

- dependency injection patterns (when needed)

A practical store setup (pseudo-code):

import { configureStore } from "@reduxjs/toolkit";

import { rootReducer } from "./rootReducer";

export const store = configureStore({

reducer: rootReducer,

middleware: (getDefaultMiddleware) =>

getDefaultMiddleware({

serializableCheck: true,

immutableCheck: true,

}),

devTools: process.env.NODE_ENV !== "production",

});

Modern advice: keep the store creation thin. Avoid stuffing app logic there. Treat it like wiring.

Actions: events, not “commands”

An action is a plain object describing what happened.

Good action names read like domain events:

cart/itemAddedsession/loggedOutcheckout/paymentConfirmed

Avoid naming actions like UI commands:

setButtonClickedtoggleModalBecauseUserPressedX

The difference matters because event names remain stable when UI changes, reducing churn and making logs meaningful.

Reducers: pure transitions with strong boundaries

Reducers are your “business logic gate.” In practice, reducers should:

- enforce invariants

- transform state predictably

- avoid side effects and random data

With createSlice, reducers become cohesive units around a piece of state:

import { createSlice } from "@reduxjs/toolkit";

const cartSlice = createSlice({

name: "cart",

initialState: { items: [], total: 0 },

reducers: {

itemAdded(state, action) {

state.items.push(action.payload);

state.total += action.payload.price;

},

itemRemoved(state, action) {

state.items = state.items.filter(i => i.id !== action.payload.id);

},

},

});

export const cartReducer = cartSlice.reducer;

export const cartActions = cartSlice.actions;

Architecturally, treat each slice as a module with a public API.

Selectors: your read model and performance boundary

Selectors are where many Redux codebases win or lose:

- They are the official “query interface” to state.

- They decouple UI from the state shape.

- Memoized selectors prevent wasted renders.

A good pattern:

- slice exports

selectXfunctions - UI imports selectors, not raw state paths

- complex computed data uses memoization (

createSelectoror equivalent)

Example:

export const selectCartItems = (state) => state.cart.items;

export const selectCartTotal = (state) => state.cart.total;

export const selectCartCount = (state) => state.cart.items.length;

If you later normalize data, move fields, or split slices, selectors shield the UI from refactor pain.

Async Redux in 2026: Thunks, Sagas, and RTK Query without dogma

Async is where most “Redux fatigue” comes from. The fix is not abandoning Redux—it’s choosing the right async tool and applying strict boundaries.

The three main async strategies

You typically have three layers of asynchronous work:

- Request lifecycle: fetch, cache, dedupe, retry, invalidate, optimistic update.

- Orchestration: sequences like “submit checkout → poll status → handle success/failure → navigate”.

- Background processes: websockets, streams, long-running workflows.

Different middleware solves different layers well.

Comparison table: Thunks vs Sagas vs RTK Query (3 columns)

| Approach | Best for | Trade-offs |

|---|---|---|

| Redux Thunk / createAsyncThunk | Simple request flows, imperative async, quick adoption | Can become messy if used for orchestration-heavy workflows; consistency depends on conventions |

| Redux Saga | Complex orchestration, cancellations, race conditions, long workflows | More concepts (effects, generators); more indirection; onboarding cost |

| RTK Query | Data fetching, caching, invalidation, optimistic updates, polling | Not designed for complex multi-step business workflows; best paired with domain actions for orchestration |

Leading architects suggest picking one default for data fetching. For many teams today, that’s RTK Query, with Thunks or Sagas reserved for orchestration.

Thunks done right: keep them thin, domain-oriented, testable

If you use Thunks, avoid embedding UI concerns and avoid “god thunks” that know too much.

A disciplined thunk style:

- validate inputs

- call a service/repository layer

- dispatch domain events

- avoid reading deep UI state

Example structure (pseudo-code):

export const submitCheckout = (payload) => async (dispatch, getState, extra) => {

dispatch(checkoutActions.submissionStarted());

try {

const result = await extra.api.checkout.submit(payload);

dispatch(checkoutActions.submissionSucceeded(result));

} catch (e) {

dispatch(checkoutActions.submissionFailed({ message: e.message }));

}

};

Notice the extra dependency injection hook. It reduces coupling and improves testability.

When Sagas are the right tool

Sagas shine when you need:

- cancellation (user navigates away mid-request)

- concurrency (race, takeLatest, takeLeading)

- long workflows (polling loops, coordinated events)

- background channels (websocket events into actions)

An example mental model:

- actions are events

- saga listens to events and orchestrates side effects

- reducers remain pure

Sagas are often overkill for CRUD-heavy apps with standard REST patterns. Use them when workflows become a product feature.

RTK Query: treat it as your API cache and request engine

RTK Query provides:

- endpoint definitions as a type-safe API layer

- caching keyed by query args

- invalidation via tags

- automatic deduplication and refetching strategies

A typical API slice:

import { createApi, fetchBaseQuery } from "@reduxjs/toolkit/query/react";

export const api = createApi({

reducerPath: "api",

baseQuery: fetchBaseQuery({ baseUrl: "/api" }),

tagTypes: ["Cart", "User"],

endpoints: (build) => ({

getCart: build.query({

query: () => "cart",

providesTags: ["Cart"],

}),

addItem: build.mutation({

query: (body) => ({ url: "cart/items", method: "POST", body }),

invalidatesTags: ["Cart"],

}),

}),

});

Architecturally, RTK Query becomes a shared infrastructure module. Your domain slices can still exist for local UI workflows, form state, and non-remote state.

A pragmatic guideline for async decisions

- If most async logic is “fetch data and cache it,” start with RTK Query.

- If async logic is “simple submit and set status,” createAsyncThunk is fine.

- If async logic is “a workflow engine,” consider Saga (or a dedicated workflow layer).

This keeps your architecture coherent and avoids mixing patterns without a reason.

Structuring a large Redux codebase: slices, selectors, and public APIs

Your Redux setup can be clean or chaotic. The difference is rarely Redux itself—it’s module boundaries.

Design principles that matter

- High cohesion: keep related state, actions, reducers, selectors together.

- Low coupling: modules should not reach into each other’s internals.

- Stable public APIs: modules export what others need, hide what they don’t.

- Isolation by default: UI reads state through selectors, not paths.

The “slice module” pattern

A robust slice module typically contains:

slice(reducers + actions)selectors(read model)types(domain types)- optional

thunks/sagas(side effects) index(public API exports)

Example (directory schema):

entities/ cart/ model/ slice.ts selectors.ts thunks.ts types.ts index.ts

And index.ts exports only what consumers should use:

export { cartReducer } from "./slice";

export { cartActions } from "./slice";

export { selectCartItems, selectCartTotal } from "./selectors";

export type { CartItem } from "./types";

This pattern reduces accidental coupling and keeps refactors safe.

Normalizing data and avoiding nested state traps

Large apps tend to store server data in deeply nested structures. That increases:

- update complexity

- bugs from partial updates

- selector complexity

- accidental duplication

Instead, normalize:

- store entities by id

- store lists of ids for ordering

- compute derived structures via selectors

With Redux Toolkit, createEntityAdapter provides a consistent normalized state shape.

Conceptually:

users: {

ids: ["u1", "u2"],

entities: { "u1": {...}, "u2": {...} }

}

Then selectors and UI can remain stable as the dataset grows.

Performance and rendering: where Redux actually helps

Redux often gets blamed for rendering issues that come from selectors and component structure.

Best practices:

- Use

useSelectorwith stable selectors. - Memoize derived data.

- Avoid selecting massive objects.

- Prefer multiple small selectors over one huge selector.

If you do this, Redux becomes a performance ally: predictable updates with minimal invalidation.

Testing: reducers and selectors are easy wins

One of Redux’s underrated benefits is testability:

- reducers are pure functions

- selectors are pure functions

- async workflows can be tested with injected dependencies

A healthy codebase has:

- unit tests for invariants in reducers

- unit tests for complex selectors

- integration tests for orchestration (thunks/sagas)

As demonstrated by projects using FSD, investing in these tests becomes cheaper over time because boundaries are stable.

Redux architecture vs UI architecture: why MVC and Atomic Design don’t solve your scaling problem

Many teams reach for “architecture” and end up improving only the UI layer, not the state layer.

MVC, MVP, MVVM: good concepts, incomplete guidance for React apps

- MVC and MVP are primarily about separating concerns in UI systems.

- MVVM helps with binding and presentation logic.

- React already encourages componentization, but it doesn’t prescribe module boundaries for business logic.

In modern frontends, the hard part is not drawing a screen. It’s managing domain complexity across many screens.

Atomic Design: excellent for UI composition, weak for domain boundaries

Atomic Design is valuable for component libraries and design systems. But it tends to organize by “visual granularity,” not by “business capability.”

You can end up with:

atoms/,molecules/,organisms/directories- shared UI that leaks domain assumptions

- unclear ownership of logic and state

Atomic Design can complement Redux, but it does not provide a strong answer to “where does the cart logic live?”

Domain-Driven Design: strong mental model, needs frontend-friendly structure

DDD introduces:

- bounded contexts

- ubiquitous language

- aggregates and invariants

These ideas are powerful for Redux: reducers often enforce invariants like a domain model. But you still need a filesystem structure that teams can follow consistently.

Comparison table: MVC vs Atomic Design vs Feature-Sliced Design (3 columns)

| Methodology | Organizing principle | Common failure mode at scale |

|---|---|---|

| MVC/MVP/MVVM | Separate UI concerns (model/view/controller) | Doesn’t strongly enforce module boundaries for features; logic gets scattered |

| Atomic Design | Visual component hierarchy | Domain logic leaks into “shared” components; unclear ownership; difficult refactors |

| Feature-Sliced Design (FSD) | Vertical slicing by business value + strict layer rules | Requires discipline to maintain public APIs and layering; initial learning curve |

Feature-Sliced Design is not a replacement for Redux Toolkit; it’s the missing organizational method that makes Redux scalable.

Modern Redux + Feature-Sliced Design: a scalable store architecture for teams

If Redux Toolkit is the engine, Feature-Sliced Design is the road system. It tells you where modules live, who can depend on whom, and how to avoid circular dependencies.

The FSD layer model and why it maps well to Redux

FSD organizes code into layers (from most general to most specific). A typical setup:

shared— reusable infrastructure and UI primitivesentities— domain objects and their model logicfeatures— user-value capabilities that operate on entitieswidgets— composed UI blocks that combine multiple features/entitiespages— route-level compositionprocesses— cross-page flows (auth, onboarding)app— initialization, providers, store, routing

Redux code maps naturally:

appholdsstorecompositionentities/*/modelholds slices, selectors, domain rulesfeatures/*/modelholds orchestration and UI state that’s feature-specificshared/apican host RTK Query base configuration

A concrete directory structure for a modern Redux Toolkit app

app/ providers/ store/ store.ts rootReducer.ts middleware.ts routes/ index.tsx

shared/ api/ baseQuery.ts api.ts lib/ ui/

entities/ user/ model/ slice.ts selectors.ts index.ts ui/

cart/ model/ slice.ts selectors.ts thunks.ts index.ts ui/

features/ add-to-cart/ model/ index.ts ui/ AddToCartButton.tsx

checkout/ model/ thunks.ts slice.ts selectors.ts index.ts ui/

widgets/ cart-drawer/ ui/

pages/ product-page/ checkout-page/

This structure gives you:

- clear ownership: entity logic stays in entities; feature orchestration stays in features

- predictable dependencies: pages depend on widgets/features/entities; entities don’t depend on pages

- safe refactors: moving a page doesn’t break entity modules

The store as an app-layer composition root

In FSD, the store belongs in app because it wires modules together.

A good root reducer composition:

entitiesreducersfeaturesreducers (optional; many features can be local component state)shared/apireducer for RTK Query if used

Pseudo-code:

import { combineReducers } from "@reduxjs/toolkit";

import { cartReducer } from "@/entities/cart";

import { userReducer } from "@/entities/user";

import { api } from "@/shared/api/api";

export const rootReducer = combineReducers({

cart: cartReducer,

user: userReducer,

[api.reducerPath]: api.reducer,

});

// In store.ts, attach middleware:

export const store = configureStore({

reducer: rootReducer,

middleware: (getDefaultMiddleware) =>

getDefaultMiddleware().concat(api.middleware),

});

This preserves layering: app composes; lower layers don’t reach upward.

Public APIs prevent “deep imports” and coupling

The fastest way to ruin a Redux architecture is deep imports like:

import { selectCartTotal } from "@/entities/cart/model/selectors"

Instead, enforce a public API:

import { selectCartTotal } from "@/entities/cart"

This single rule dramatically improves modularity. It also makes code reviews easier: deep imports are a code smell.

Where should “UI state” live?

Not everything belongs in Redux. A pragmatic approach:

- Local component state: input typing, focus, hover, transient toggles.

- Feature state in Redux: multi-component coordination, persistence across routes, complex step flows.

- Entity state in Redux: domain facts and invariants (cart contents, session status).

- Server state: prefer RTK Query caching rather than manual slice duplication.

This keeps Redux for what it does best: shared, meaningful, long-lived state transitions.

Step-by-step: building a scalable Redux Toolkit module with FSD boundaries

This is a repeatable blueprint you can apply across features.

Step 1: Define the domain slice in entities

Create entities/cart/model/slice.ts:

- define initial state

- define reducers as domain events

- export reducer and actions

Example invariants to encode:

- total never negative

- quantity cannot be zero

- item IDs unique

Step 2: Create selectors as the read model

Create entities/cart/model/selectors.ts:

- expose stable selectors for UI and features

- compute derived data (count, totals, flags)

Avoid exporting raw state access patterns. Selectors are your “database queries.”

Step 3: Add async only if it’s truly part of the domain

If cart operations depend on server state:

- prefer RTK Query endpoints for fetching/syncing

- or keep thunks in

entities/cart/model/thunks.tsif you need domain-driven side effects

Keep async logic isolated and injectable.

Step 4: Expose a public API

In entities/cart/index.ts export:

cartReducercartActionsselectors

Do not export internal helpers unless you want them as stable APIs.

Step 5: Consume the module from features and UI

In features/add-to-cart/ui/AddToCartButton.tsx:

- dispatch domain events (actions)

- select data via selectors

This is how you keep UI simple and consistent.

Step 6: Review dependencies in code review

Create a simple checklist:

- Does

entitiesimport fromfeaturesorpages? (It shouldn’t.) - Are there deep imports bypassing public APIs?

- Are selectors returning unstable objects?

- Is async logic mixing UI concerns?

These practices prevent architecture decay.

Do you still need Redux in a world of hooks and other libraries?

This is the decision many teams are making. The honest answer: it depends—but Redux still has a strong place.

When Redux Toolkit is a great fit

- Your app has non-trivial domain state shared across many screens.

- You need predictable debugging (action logs, time-travel style diagnosis).

- Your team size is growing and you need consistent conventions.

- You value testable state transitions and stable module boundaries.

- You want a robust solution for async patterns with RTK Query or middleware.

When Redux might be unnecessary overhead

- The app is mostly static with little shared state.

- State is predominantly local to a few components.

- Data fetching is simple and can be handled by a dedicated server-state library.

- You don’t need global event observability.

Comparison table: Redux Toolkit vs lightweight stores vs server-state tools (3 columns)

| Option | Best for | Trade-offs |

|---|---|---|

| Redux Toolkit | Complex shared state, large teams, predictable transitions | Requires structure; needs discipline around selectors and module boundaries |

| Lightweight stores (e.g., small state containers) | Small apps, quick prototypes, minimal ceremony | Can drift into inconsistent patterns; fewer guardrails for large teams |

| Server-state libraries (query caching) | Remote data caching and synchronization | Doesn’t replace domain state management; still need a strategy for local invariants |

A pragmatic approach is to combine tools:

- RTK Query for server state

- Redux slices for domain invariants and cross-feature coordination

- local state for transient UI concerns

This hybrid is often the most productive and maintainable.

Common Redux Toolkit mistakes and how to avoid them

These issues show up repeatedly in large codebases.

Mistake 1: Treating Redux as a dumping ground

Symptom: everything goes into the store, including transient UI flags.

Fix:

- keep UI-local state local

- store only what needs to be shared, persisted, or audited

Mistake 2: Deep imports and leaking internals

Symptom: modules import each other’s file paths directly.

Fix:

- enforce public APIs with

index.ts - add lint rules or path restrictions

- review dependency direction as part of architecture

Mistake 3: Selectors returning unstable objects

Symptom: components re-render more than expected.

Fix:

- memoize derived selectors

- return primitives or stable references

- avoid allocating new arrays/objects in selectors without memoization

Mistake 4: Duplicating server state manually

Symptom: you fetch data into a slice and also keep separate copies.

Fix:

- use RTK Query cache as the source of truth

- keep domain slices for non-remote state and invariants

Mistake 5: Mixing async patterns randomly

Symptom: some features use thunks, some sagas, some direct fetch in components.

Fix:

- choose a default (often RTK Query + occasional thunks)

- document conventions and enforce them in reviews

These are not “Redux problems.” They are architecture consistency problems—and that’s exactly where FSD provides long-term leverage.

Conclusion

Modern Redux is not about boilerplate; it’s about predictable state transitions, strong module boundaries, and scalable team workflows. Redux Toolkit gives you pragmatic defaults—slices, good store configuration, and optional RTK Query for caching—while Feature-Sliced Design provides the structural rules that keep large codebases cohesive and low-coupled. If you combine them thoughtfully, you reduce refactor fear, speed up onboarding, and make async behavior easier to reason about. The result is an architecture that stays understandable even as your product grows and requirements change. Ready to build scalable and maintainable frontend projects? Dive into the official Feature-Sliced Design Documentation to get started. Have questions or want to share your experience? Visit our homepage to learn more!