The Simplicity of Parcel's Zero-Config Arch

TLDR:

Learn how Parcel’s zero-config architecture bundles an app from a single HTML entry, with built-in TypeScript, CSS, and asset handling. We’ll unpack Parcel’s plugin-based pipeline, persistent caching, and the small set of “parcel config” levers—targets and .parcelrc—then compare Parcel vs Vite. Finally, see how Feature-Sliced Design keeps large frontends modular, cohesive, and refactor-friendly.

Parcel is a zero-config bundler that turns an HTML entry into a complete asset pipeline, so you can ship without maintaining a sprawling webpack config or a fragile chain of plugins. That simplicity matters most as your codebase grows: fast rebuilds, automatic code splitting, and sensible defaults reduce build friction, while a structured architecture like Feature-Sliced Design (FSD) from feature-sliced.design keeps the source code scalable and easy to change.

Zero-config bundling: get a project running in minutes

A build tool is part of your architecture. It decides how modules are resolved, transformed, bundled, cached, and deployed. The common failure mode is letting “setup” become a hidden product: custom configs, undocumented loaders, and “don’t touch this” scripts that slow the whole team.

The idea behind Parcel’s zero-config arch is deliberately small: start from an entry and let conventions do the work. In practice, the entry is usually an HTML file, and everything else is discovered through dependencies.

Step-by-step: the minimal setup (no config files)

- Initialize

- Create a folder and run

npm init -y(or Yarn / pnpm).

- Create a folder and run

- Install

- Add Parcel:

npm i -D parcel.

- Add Parcel:

- Create an entry

src/index.htmlwith:<script type="module" src="./main.ts"></script><link rel="stylesheet" href="./styles.css">

- Run dev

parcel src/index.html(this is shorthand forparcel serve).

- Build production

parcel build src/index.html(minification and other production optimizations are enabled by default).

That’s the essence of a “zero config bundler”: the default pipeline (@parcel/config-default) already knows how to handle common web assets and can extend itself when you introduce new file types.

Why “HTML as the entry” is a productivity feature

Many build setups treat HTML as a template to be bolted on later. Parcel treats it as a first-class root of the dependency graph, which has practical benefits:

- Multi-page apps are natural. Pass multiple entries like

parcel 'src/pages/*.html'and each page remains an entry bundle. - Assets are dependencies everywhere. A

<link>, an<img>, andnew URL("logo.png", import.meta.url)are all tracked by the same graph. - Teams get a shared mental model. “If it’s referenced, it’s built” is easier to teach than a pile of special cases.

A key principle in software engineering is to minimize incidental complexity so teams spend energy on the domain. Zero-config helps by shrinking the number of build decisions you need to make on day one.

A tiny package.json that improves onboarding

Even with zero config, create explicit scripts early:

dev:parcel src/index.htmlbuild:parcel build src/index.htmlwatch:parcel watch src/index.html(rebuilds without serving)check:tsc --noEmit(type checking in CI)

Those scripts set expectations: Parcel bundles; other tools validate correctness. That separation scales better than “one command does everything”.

What “zero-config” really means: defaults, conventions, and graphs

Zero-config is not “no behavior”. It’s “behavior you don’t have to describe”. Parcel (especially v2) achieves this through a graph-based pipeline plus a plugin system that selects defaults based on file types.

The core mental model: Asset Graph → Bundle Graph

The plugin system defines two key structures:

- Asset Graph: all assets (often files) and their dependencies.

- Bundle Graph: the asset graph plus bundling decisions (entries, async bundles, shared bundles).

Think of a directed graph:

- Nodes:

index.html,main.ts,styles.css,logo.png, … - Edges: “depends on” relationships (imports, URLs, links)

The build runs in phases:

- Resolving + transforming (in parallel) to discover assets and convert them

- Bundling to group assets into bundles

- Naming to choose output file names

- Packaging + optimizing + compressing (in parallel) to emit final files, including content hashes and optional gzip/brotli

This is why the setup feels consistent across projects: you supply inputs, and the pipeline stays stable.

Plugin types explain the architecture

Extensibility is not a grab-bag of hooks. It is organized into plugin types with clear responsibilities:

- Transformer: convert one asset type to another (e.g., TypeScript → JS)

- Resolver: map a dependency request to a file/path

- Bundler / Packager / Optimizer / Compressor: define how outputs are created, optimized, and encoded

- Reporter / Validator: observe the build and emit diagnostics (including type checks via plugins)

Leading architects suggest that scalable systems embrace composability and clear boundaries. This plugin-driven design applies those ideas to the build itself.

Conventions that matter in real projects

The conventions are intentionally few, but high leverage:

- Entries are explicit: via CLI entries or

package.json#source - Outputs are predictable: default

dist/, overridable via--dist-dirortargets - Caching is built-in: default

.parcel-cache, overridable via--cache-diror disabled with--no-cache - Auto-install reduces friction: adding Sass or other formats can trigger automatic devDependency installation

The result is a repeatable setup that new teammates can learn quickly.

Out-of-the-box features that remove 80% of bundler work

Its “batteries included” story is what makes the zero-config bundler claim believable. You get a cohesive asset pipeline rather than a pile of one-off integrations.

TypeScript: fast transpilation, explicit type checks

The default behavior transpiles .ts and .tsx out of the box, optimized for speed by compiling files individually. By default, it does not type check—and that’s often a win: bundling stays fast, and correctness checks become explicit.

A robust workflow for teams:

- Local: rely on editor TypeScript support.

- CI: run

tsc --noEmitalongsideparcel build.

If you need compilation behavior that the default transformer doesn’t support, the Parcel docs describe switching to a TSC-based transformer via .parcelrc (@parcel/transformer-typescript-tsc). It still compiles per-file (so isolatedModules constraints matter), but it can help when you need closer alignment with tsc.

JSX, framework ergonomics, and fast feedback loops

JSX works without configuration. With React, you can get a smooth Fast Refresh experience, and CSS changes apply via HMR with no full page reload.

That’s not just “nice DX”. It has architectural consequences:

- Faster iteration encourages smaller, safer refactors.

- Teams are more willing to improve boundaries (public APIs, slices) because feedback is immediate.

CSS: modules, PostCSS, and sibling bundles

CSS is part of the dependency graph:

- Import CSS from JS and the build emits a sibling CSS bundle that loads in parallel.

- Use CSS Modules when you want local scoping.

- Add PostCSS when you need autoprefixing or modern syntax.

Because this is default behavior, you can keep styling decisions local—high cohesion with less global coupling.

Images and assets: optimization as a default, customization as an option

You can resize/convert images using query parameters, for example:

hero.jpg?width=1200avatar.png?as=webp&quality=80

In production, lossless optimization for JPEG/PNG is enabled by default, and you can disable or adjust image optimizers via .parcelrc. The architectural win is that optimization is built in, not a separate pipeline to maintain.

Code splitting, content hashing, and browser caching

Dynamic import() creates async bundles, shared bundles are extracted automatically, and output filenames include content hashes for long-term caching.

That aligns well with scalable frontend structure: isolated features become isolated bundles more naturally, and stable public APIs reduce accidental “pull everything into the main chunk” mistakes.

Caching and rebuild speed: the hidden superpower

In large codebases, build performance is a daily cost center. The approach here is principled: cache everything and invalidate precisely.

What gets tracked for invalidation

Build artifacts are cached to disk (by default in .parcel-cache) and restored across restarts. The tool also tracks the inputs that affect outputs, including:

- Source files

- Relevant config files

- Plugins and involved devDependencies

When something changes, only the affected part of the graph needs rebuilding. The result is a healthier cost curve: rebuild time becomes closer to “proportional to the change”, not “proportional to the repo size”.

Practical performance tactics that work in teams

- Cache

.parcel-cachein CI (where supported) to turn repeated builds into warm builds. - Use

--lazyfor large multi-page apps:parcel 'pages/*.html' --lazybuilds only what is requested in the browser. - Keep repos out of cloud-synced folders to avoid noisy file events and unnecessary rebuilds.

- Don’t delete cache by default. Clear

.parcel-cacheonly when troubleshooting inconsistent state.

These are low-effort habits with high ROI, especially when onboarding new developers or maintaining multiple environments.

Configuration that stays readable: targets, .parcelrc, and team defaults

Zero-config gets you started; configuration keeps you aligned with real-world constraints. The goal is not “never configure”—it’s configure with intent and keep the surface area small.

Most parcel config questions fall into a few buckets: output shape, target environments, and small pipeline tweaks. Keeping those decisions explicit (and minimal) makes builds easier to reason about.

Targets: build multiple environments without inventing new pipelines

Targets support multiple builds simultaneously, each with its own environment and output settings:

- Modern vs legacy browsers

- Browser vs Node

- App vs library outputs (

main,module,types)

Targets live in package.json, keeping build intent close to project metadata. There’s also differential bundling: when an HTML entry uses <script type="module"> and the browserslist includes browsers without native ESM support, a nomodule fallback can be generated automatically.

This is the kind of configuration that still feels simple: you describe what you need, and the pipeline handles how to produce it.

.parcelrc: extend defaults without losing the plot

Most teams touch .parcelrc for focused reasons:

- Use a different transformer for a file type

- Add a validator (e.g., TypeScript validator plugin, documented as experimental)

- Add compressors (gzip/brotli) or adjust optimizers

- Add a custom namer or reporter for org-specific needs

A good rule: change one thing at a time, and keep .parcelrc close to the default by extending @parcel/config-default.

Shared configuration packages for organizations

You can publish a .parcelrc as an npm package so multiple projects share the same build policy. This is a strong governance move:

- Consistent builds across teams

- Less “config drift”

- Easier upgrades and migrations

It mirrors a broader architectural truth: standards are a force multiplier when they’re easy to adopt.

The one “gotcha” to plan for: TypeScript path aliases

The Parcel docs note that TypeScript’s baseUrl/paths resolution extensions are not fully supported. If your org standardizes on TS path aliases, plan a strategy:

- Prefer stable public APIs and meaningful slice boundaries (often reduces alias pressure).

- Use supported specifiers (absolute/tilde) where possible.

- If needed, introduce a resolver plugin specifically for TS paths and document it as a deliberate choice.

This keeps the build tool from becoming the place where architectural confusion is “fixed” with more config.

From bundler simplicity to product-scale architecture: why FSD matters

A fast bundler won't prevent "spaghetti code". The long-term pain points at scale are architectural:

- High coupling (ripple effects)

- Low cohesion (unrelated code co-located)

- Deep imports that bypass intended boundaries

- Refactors that feel unsafe

Feature-Sliced Design addresses these with a methodology that encodes boundaries into the folder structure and import rules.

Comparing common frontend structuring approaches

| Approach | What it optimizes | Typical scaling failure |

|---|---|---|

| MVC / MVP | Separation by technical role | “Controller/Presenter” becomes a dumping ground; boundaries blur |

| Atomic Design | Consistent UI composition | Doesn’t organize domain logic or product features well |

| Domain-Driven Design (DDD) | Strong domain boundaries | Can be heavy for UI; requires careful adaptation |

| Feature-Sliced Design (FSD) | Feature-first modularity + layered dependency gradient | Requires discipline with import rules and public APIs |

Atomic Design and FSD are often complementary: use Atomic patterns inside shared/ui (tokens, primitives, patterns) while FSD structures product logic around features and entities.

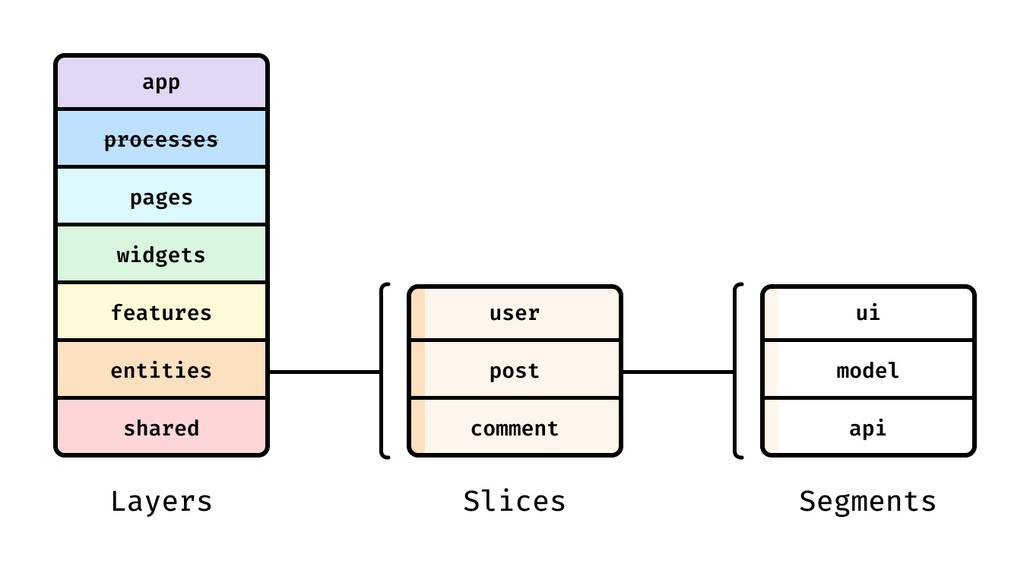

The FSD hierarchy: layers → slices → segments

FSD standardizes seven layers (top to bottom):

app(routing, providers, entrypoints)processes(deprecated in current reference, sometimes present in legacy)pageswidgetsfeaturesentitiesshared

Layers set dependency direction. The import rule is simple and powerful: a module can only import from layers strictly below. Slices (like features/auth or entities/user) group code by business meaning, and segments inside slices group code by purpose (ui, model, api, lib, config).

This is a practical way to improve cohesion and reduce coupling, without requiring a heavy framework.

Public APIs: explicit contracts that enable refactors

FSD emphasizes defining a public API for each slice (often an index.ts that re-exports what other layers are allowed to use). This acts as a contract and improves isolation: you can refactor internals without breaking consumers.

- The rest of the app is protected from internal refactors.

- Only necessary parts are exposed, improving discoverability.

- Imports become consistent and reviewable.

This also plays well with bundlers: fewer deep imports means fewer accidental dependency tangles and fewer circular-import surprises.

Parcel + Feature-Sliced Design: a workflow that scales with teams

The build doesn’t care how you structure src/, which is precisely why structure matters. A pragmatic combo is:

- Parcel for a minimal, predictable build pipeline

- FSD for predictable source boundaries

A tangible directory structure with an obvious entry

src/app/index.html(Parcel entry)main.tsx(bootstrapping)providers/(router/store/i18n)

pages/widgets/features/entities/shared/(ui,api,lib,config)

Keep the entry in app/, keep business code in slices, and keep “generic building blocks” in shared/. This gives new developers a map they can trust.

Actionable team practices

- Review PRs for layer-rule violations the same way you review type errors.

- Keep slice public APIs intentional (avoid “export * everything” as a default).

- Use targets only when needed; keep the default build path boring.

- Let architecture solve architecture problems—don’t solve them by growing bundler config.

Parcel vs Vite: a clear-eyed comparison for decision-makers

Parcel and Vite both deliver excellent developer experience, but they optimize different workflows.

Parcel vs Vite in one table

| Dimension | Parcel | Vite |

|---|---|---|

| Dev model | Bundler + dev server | Native ESM dev server; bundling mainly for production |

| Entry model | HTML-first entries, multi-page friendly | Framework templates; HTML is usually part of a single app entry |

| Performance angle | Persistent cache + parallel graph processing | Dependency pre-bundling with esbuild, often 10–100× faster than JS-based bundlers for that step |

| Extensibility | .parcelrc plugin pipeline and shared config packages | vite.config.* plus large plugin ecosystem |

When to choose each

Choose Parcel when you want:

- A cohesive, low-config asset pipeline (HTML/CSS/images/TS) with minimal setup

- Multi-entry or multi-page builds without extra plumbing

- Targets and differential bundling as a first-class feature

Choose Vite when you want:

- An ESM-first dev server model and a strong framework-first ecosystem

- Vite/Rollup plugin compatibility as a primary requirement

- A small, explicit config file you’re happy to maintain (

vite.config.*)

Either way, architecture is the long game. Using FSD helps you keep your codebase understandable and stable as requirements change, regardless of the build tool.

Further reading: docs worth bookmarking

- Parcel Documentation — the entry point for CLI, production builds, and recipes

- Parcel CLI reference —

serve,watch,build, and the most useful flags - Parcel Plugin System Overview — asset graph, bundle graph, and plugin phases

- Parcel TypeScript — transpilation, TSC transformer, and type-checking options

- Parcel Targets — multi-target builds and differential bundling

- Feature-Sliced Design Overview — layers, slices, segments, and the import rule

Conclusion

Parcel’s zero-config arch works because it is structured, not magical: it builds an asset graph, applies strong defaults through a plugin pipeline, and stays fast with persistent caching and precise invalidation. You can bundle from an HTML entry in minutes, then grow into targets and .parcelrc customization only when your product demands it.

For long-term maintainability, pair that build simplicity with Feature-Sliced Design. FSD’s layer rule, feature-first slices, and public APIs create clear boundaries that reduce coupling and increase cohesion—exactly what large teams need to refactor safely, onboard quickly, and ship consistently.

Whether you choose Parcel or Vite, treat the bundler as supporting infrastructure: keep configuration small, automate checks in CI, and let your architecture—not tooling—define the boundaries.

Ready to build scalable and maintainable frontend projects? Dive into the official Feature-Sliced Design Documentation to get started.

Have questions or want to share your experience? Visit our homepage to learn more!

Disclaimer: The architectural patterns discussed in this article are based on the Feature-Sliced Design methodology. For detailed implementation guides and the latest updates, please refer to the official documentation.