Tutorial

Part 1. On paper

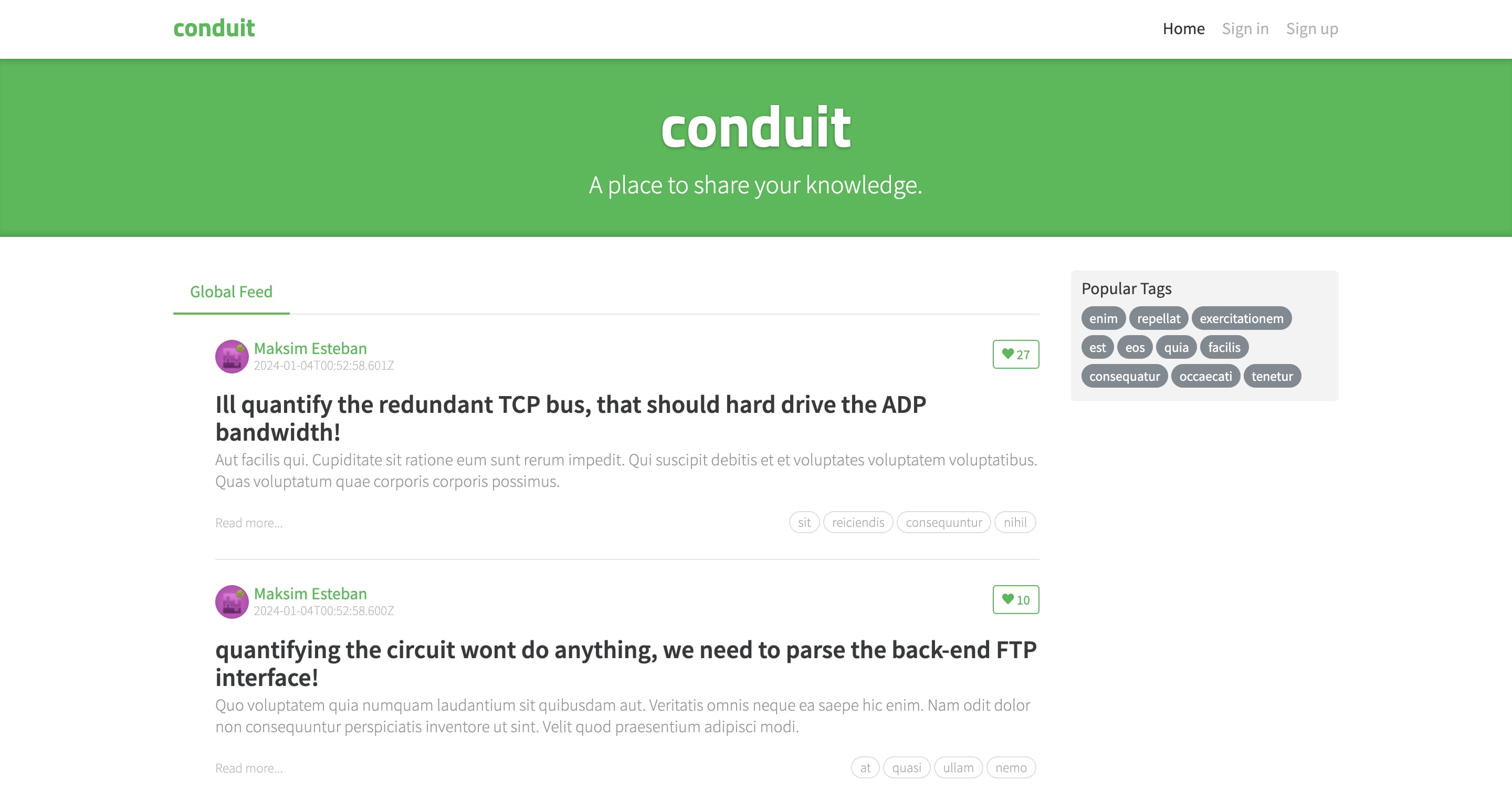

This tutorial will examine the Real World App, also known as Conduit. Conduit is a basic Medium clone — it lets you read and write articles as well as comment on the articles of others.

This is a pretty small application, so we will keep it simple and avoid excessive decomposition. It’s highly likely that the entire app will fit into just three layers: App, Pages, and Shared. If not, we will introduce additional layers as we go. Ready?

Start by listing the pages

If we look at the screenshot above, we can assume at least the following pages:

- Home (article feed)

- Sign in and sign up

- Article reader

- Article editor

- User profile viewer

- User profile editor (user settings)

Every one of these pages will become its own slice on the Pages layer. Recall from the overview that slices are simply folders inside of layers and layers are simply folders with predefined names like pages.

As such, our Pages folder will look like this:

📂 pages/

📁 feed/

📁 sign-in/

📁 article-read/

📁 article-edit/

📁 profile/

📁 settings/

The key difference of Feature-Sliced Design from an unregulated code structure is that pages cannot reference each other. That is, one page cannot import code from another page. This is due to the import rule on layers:

A module (file) in a slice can only import other slices when they are located on layers strictly below.

In this case, a page is a slice, so modules (files) inside this page can only reference code from layers below, not from the same layer, Pages.

Close look at the feed

Anonymous user’s perspective

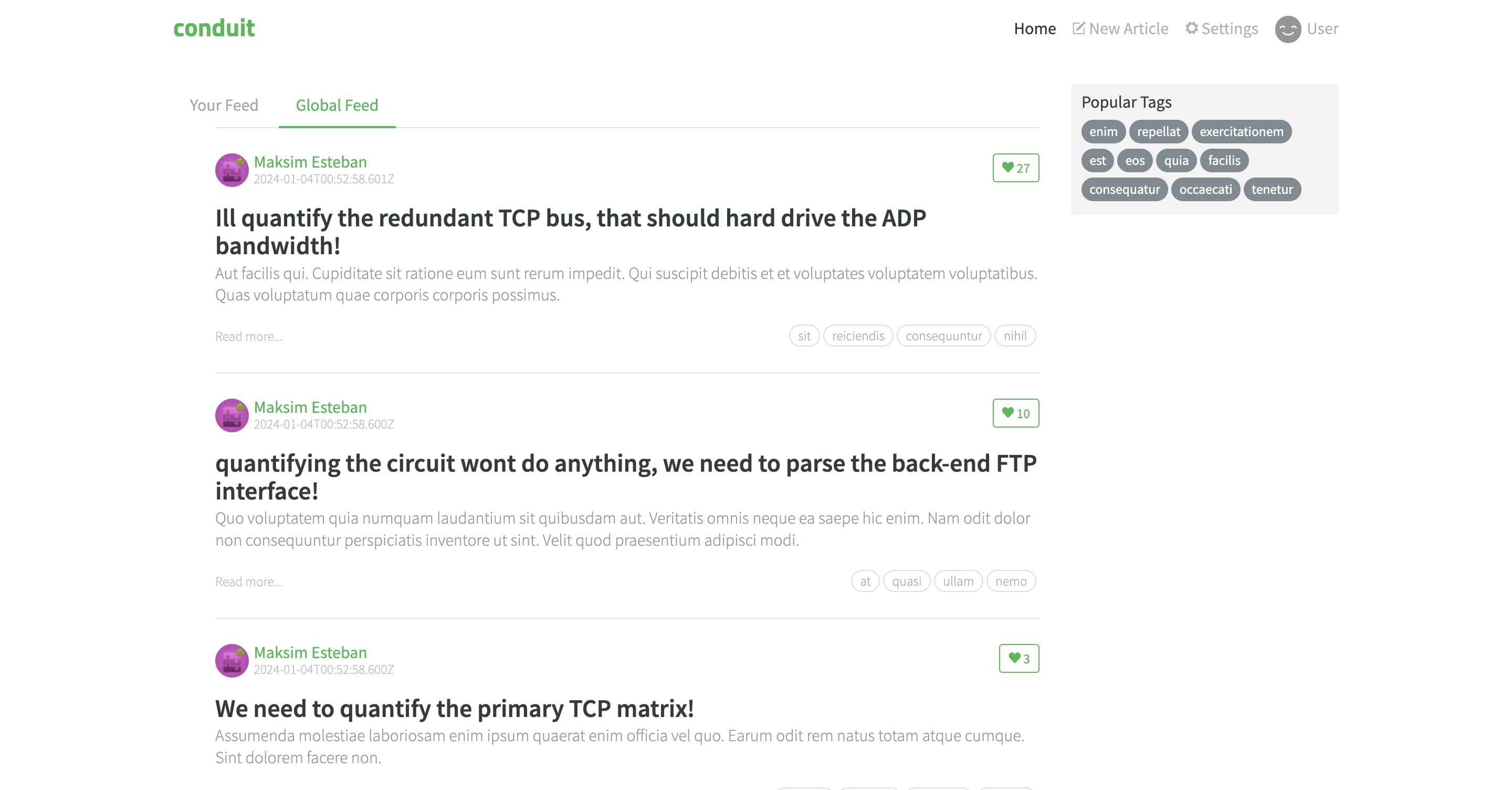

Authenticated user’s perspective

There are three dynamic areas on the feed page:

- Sign-in links with an indication if you are signed in

- List of tags that triggers filtering in the feed

- One/two feeds of articles, each article with a like button

The sign-in links are a part of a header that is common to all pages, we will revisit it separately.

List of tags

To build the list of tags, we need to fetch the available tags, render each tag as a chip, and store the selected tags in a client-side storage. These operations fall into categories “API interaction”, “user interface”, and “storage”, respectively. In Feature-Sliced Design, code is separated by purpose using segments. Segments are folders in slices, and they can have arbitrary names that describe the purpose, but some purposes are so common that there’s a convention for certain segment names:

- 📂

api/for backend interactions - 📂

ui/for code that handles rendering and appearance - 📂

model/for storage and business logic - 📂

config/for feature flags, environment variables and other forms of configuration

We will place code that fetches tags into api, the tag component into ui, and the storage interaction into model.

Articles

Using the same grouping principles, we can decompose the feed of articles into the same three segments:

- 📂

api/: fetch paginated articles with like count; like an article - 📂

ui/:- tab list that can render an extra tab if a tag is selected

- individual article

- functional pagination

- 📂

model/: client-side storage of the currently loaded articles and current page (if needed)

Reuse generic code

Most pages are very different in intent, but certain things stay the same across the entire app — for example, the UI kit that conforms to the design language, or the convention on the backend that everything is done with a REST API with the same authentication method. Since slices are meant to be isolated, code reuse is facilitated by a lower layer, Shared.

Shared is different from other layers in the sense that it contains segments, not slices. In this way, the Shared layer can be thought of as a hybrid between a layer and a slice.

Usually, the code in Shared is not planned ahead of time, but rather extracted during development, because only during development does it become clear which parts of code are actually shared. However, it’s still helpful to keep a mental note of what kind of code naturally belongs in Shared:

- 📂

ui/— the UI kit, pure appearance, no business logic. For example, buttons, modal dialogs, form inputs. - 📂

api/— convenience wrappers around request making primitives (likefetch()on the Web) and, optionally, functions for triggering particular requests according to the backend specification. - 📂

config/— parsing environment variables - 📂

i18n/— configuration of language support - 📂

router/— routing primitives and route constants

Those are just a few examples of segment names in Shared, but you can omit any of them or create your own. The only important thing to remember when creating new segments is that segment names should describe purpose (the why), not essence (the what). Names like “components”, “hooks”, “modals” should not be used because they describe what these files are, but don’t help to navigate the code inside. This requires people on the team to dig through every file in such folders and also keeps unrelated code close, which leads to broad areas of code being affected by refactoring and thus makes code review and testing harder.

Define a strict public API

In the context of Feature-Sliced Design, the term public API refers to a slice or segment declaring what can be imported from it by other modules in the project. For example, in JavaScript that can be an index.js file re-exporting objects from other files in the slice. This enables freedom in refactoring code inside a slice as long as the contract with the outside world (i.e. the public API) stays the same.

For the Shared layer that has no slices, it’s usually more convenient to define a separate public API for each segment as opposed to defining one single index of everything in Shared. This keeps imports from Shared naturally organized by intent. For other layers that have slices, the opposite is true — it’s usually more practical to define one index per slice and let the slice decide its own set of segments that is unknown to the outside world because other layers usually have a lot less exports.

Our slices/segments will appear to each other as follows:

📂 pages/

📂 feed/

📄 index

📂 sign-in/

📄 index

📂 article-read/

📄 index

📁 …

📂 shared/

📂 ui/

📄 index

📂 api/

📄 index

📁 …

Whatever is inside folders like pages/feed or shared/ui is only known to those folders, and other files should not rely on the internal structure of these folders.

Large reused blocks in the UI

Earlier we made a note to revisit the header that appears on every page. Rebuilding it from scratch on every page would be impractical, so it’s only natural to want to reuse it. We already have Shared to facilitate code reuse, however, there’s a caveat to putting large blocks of UI in Shared — the Shared layer is not supposed to know about any of the layers above.

Between Shared and Pages there are three other layers: Entities, Features, and Widgets. Some projects may have something in those layers that they need in a large reusable block, and that means we can’t put that reusable block in Shared, or else it would be importing from upper layers, which is prohibited. That’s where the Widgets layer comes in. It is located above Shared, Entities, and Features, so it can use them all.

In our case, the header is very simple — it’s a static logo and top-level navigation. The navigation needs to make a request to the API to determine if the user is currently logged in or not, but that can be handled by a simple import from the api segment. Therefore, we will keep our header in Shared.

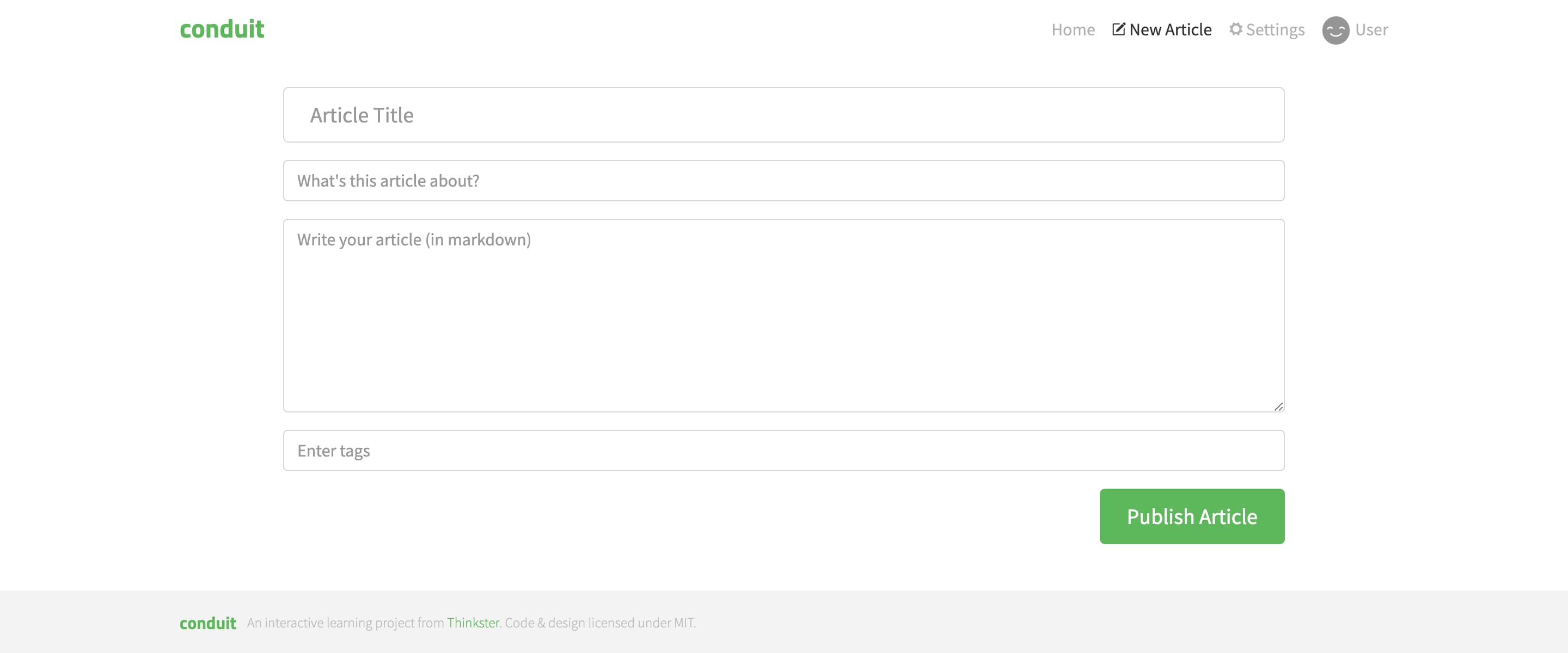

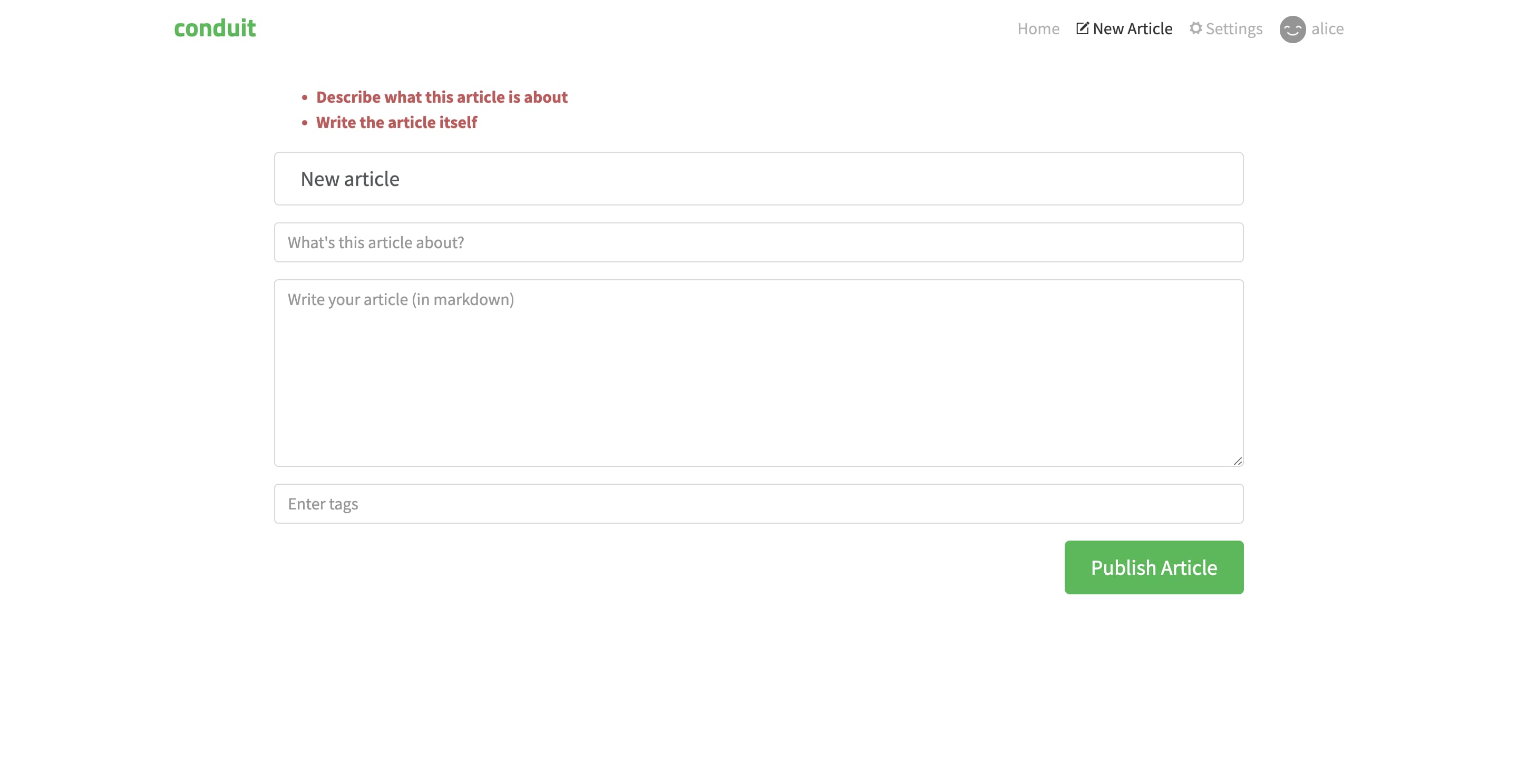

Close look at a page with a form

Let’s also examine a page that’s intended for editing, not reading. For example, the article writer:

It looks trivial, but contains several aspects of application development that we haven’t explored yet — form validation, error states, and data persistence.

If we were to build this page, we would grab some inputs and buttons from Shared and put together a form in the ui segment of this page. Then, in the api segment, we would define a mutation request to create the article on the backend.

To validate the request before sending, we need a validation schema, and a good place for it is the model segment, since it’s the data model. There we will produce error messages and display them using another component in the ui segment.

To improve user experience, we could also persist the inputs to prevent accidental data loss. This is also a job of the model segment.

Summary

We have examined several pages and outlined a preliminary structure for our application:

- Shared layer

uiwill contain our reusable UI kitapiwill contain our primitive interactions with the backend- The rest will be arranged on demand

- Pages layer — each page is a separate slice

uiwill contain the page itself and all of its partsapiwill contain more specialized data fetching, usingshared/apimodelmight contain client-side storage of the data that we will display

Let’s get building!

Part 2. In code

Now that we have a plan, let’s put it to practice. We will use React and Remix.

There's a template ready for this project, clone it from GitHub to get a headstart: https://github.com/feature-sliced/tutorial-conduit/tree/clean.

Install dependencies with npm install and start the development server with npm run dev. Open http://localhost:3000 and you should see a blank app.

Lay out the pages

Let’s start by creating blank components for all our pages. Run the following command in your project:

npx fsd pages feed sign-in article-read article-edit profile settings --segments ui

This will create folders like pages/feed/ui/ and an index file, pages/feed/index.ts, for every page.

Connect the feed page

Let’s connect the root route of our application to the feed page. Create a component, FeedPage.tsx in pages/feed/ui and put the following inside it:

export function FeedPage() {

return (

<div className="home-page">

<div className="banner">

<div className="container">

<h1 className="logo-font">conduit</h1>

<p>A place to share your knowledge.</p>

</div>

</div>

</div>

);

}

Then re-export this component in the feed page’s public API, the pages/feed/index.ts file:

export { FeedPage } from "./ui/FeedPage";

Now connect it to the root route. In Remix, routing is file-based, and the route files are located in the app/routes folder, which nicely coincides with Feature-Sliced Design.

Use the FeedPage component in app/routes/_index.tsx:

import type { MetaFunction } from "@remix-run/node";

import { FeedPage } from "pages/feed";

export const meta: MetaFunction = () => {

return [{ title: "Conduit" }];

};

export default FeedPage;

Then, if you run the dev server and open the application, you should see the Conduit banner!

API client

To talk to the RealWorld backend, let’s create a convenient API client in Shared. Create two segments, api for the client and config for variables like the backend base URL:

npx fsd shared --segments api config

Then create shared/config/backend.ts:

export { mockBackendUrl as backendBaseUrl } from "mocks/handlers";

export { backendBaseUrl } from "./backend";

Since the RealWorld project conveniently provides an OpenAPI specification, we can take advantage of auto-generated types for our client. We will use the openapi-fetch package that comes with an additional type generator.

Run the following command to generate up-to-date API typings:

npm run generate-api-types

This will create a file shared/api/v1.d.ts. We will use this file to create a typed API client in shared/api/client.ts:

import createClient from "openapi-fetch";

import { backendBaseUrl } from "shared/config";

import type { paths } from "./v1";

export const { GET, POST, PUT, DELETE } = createClient<paths>({ baseUrl: backendBaseUrl });

export { GET, POST, PUT, DELETE } from "./client";

Real data in the feed

We can now proceed to adding articles to the feed, fetched from the backend. Let’s begin by implementing an article preview component.

Create pages/feed/ui/ArticlePreview.tsx with the following content:

export function ArticlePreview({ article }) { /* TODO */ }

Since we’re writing in TypeScript, it would be nice to have a typed article object. If we explore the generated v1.d.ts, we can see that the article object is available through components["schemas"]["Article"]. So let’s create a file with our data models in Shared and export the models:

import type { components } from "./v1";

export type Article = components["schemas"]["Article"];

export { GET, POST, PUT, DELETE } from "./client";

export type { Article } from "./models";

Now we can come back to the article preview component and fill the markup with data. Update the component with the following content:

import { Link } from "@remix-run/react";

import type { Article } from "shared/api";

interface ArticlePreviewProps {

article: Article;

}

export function ArticlePreview({ article }: ArticlePreviewProps) {

return (

<div className="article-preview">

<div className="article-meta">

<Link to={`/profile/${article.author.username}`} prefetch="intent">

<img src={article.author.image} alt="" />

</Link>

<div className="info">

<Link

to={`/profile/${article.author.username}`}

className="author"

prefetch="intent"

>

{article.author.username}

</Link>

<span className="date" suppressHydrationWarning>

{new Date(article.createdAt).toLocaleDateString(undefined, {

dateStyle: "long",

})}

</span>

</div>

<button className="btn btn-outline-primary btn-sm pull-xs-right">

<i className="ion-heart"></i> {article.favoritesCount}

</button>

</div>

<Link

to={`/article/${article.slug}`}

className="preview-link"

prefetch="intent"

>

<h1>{article.title}</h1>

<p>{article.description}</p>

<span>Read more...</span>

<ul className="tag-list">

{article.tagList.map((tag) => (

<li key={tag} className="tag-default tag-pill tag-outline">

{tag}

</li>

))}

</ul>

</Link>

</div>

);

}

The like button doesn’t do anything for now, we will fix that when we get to the article reader page and implement the liking functionality.

Now we can fetch the articles and render out a bunch of these cards. Fetching data in Remix is done with loaders — server-side functions that fetch exactly what a page needs. Loaders interact with the API on the page’s behalf, so we will put them in the api segment of a page:

import { json } from "@remix-run/node";

import { GET } from "shared/api";

export const loader = async () => {

const { data: articles, error, response } = await GET("/articles");

if (error !== undefined) {

throw json(error, { status: response.status });

}

return json({ articles });

};

To connect it to the page, we need to export it with the name loader from the route file:

export { FeedPage } from "./ui/FeedPage";

export { loader } from "./api/loader";

import type { MetaFunction } from "@remix-run/node";

import { FeedPage } from "pages/feed";

export { loader } from "pages/feed";

export const meta: MetaFunction = () => {

return [{ title: "Conduit" }];

};

export default FeedPage;

And the final step is to render these cards in the feed. Update your FeedPage with the following code:

import { useLoaderData } from "@remix-run/react";

import type { loader } from "../api/loader";

import { ArticlePreview } from "./ArticlePreview";

export function FeedPage() {

const { articles } = useLoaderData<typeof loader>();

return (

<div className="home-page">

<div className="banner">

<div className="container">

<h1 className="logo-font">conduit</h1>

<p>A place to share your knowledge.</p>

</div>

</div>

<div className="container page">

<div className="row">

<div className="col-md-9">

{articles.articles.map((article) => (

<ArticlePreview key={article.slug} article={article} />

))}

</div>

</div>

</div>

</div>

);

}

Filtering by tag

Regarding the tags, our job is to fetch them from the backend and to store the currently selected tag. We already know how to do fetching — it’s another request from the loader. We will use a convenience function promiseHash from a package remix-utils, which is already installed.

Update the loader file, pages/feed/api/loader.ts, with the following code:

import { json } from "@remix-run/node";

import type { FetchResponse } from "openapi-fetch";

import { promiseHash } from "remix-utils/promise";

import { GET } from "shared/api";

async function throwAnyErrors<T, O, Media extends `${string}/${string}`>(

responsePromise: Promise<FetchResponse<T, O, Media>>,

) {

const { data, error, response } = await responsePromise;

if (error !== undefined) {

throw json(error, { status: response.status });

}

return data as NonNullable<typeof data>;

}

export const loader = async () => {

return json(

await promiseHash({

articles: throwAnyErrors(GET("/articles")),

tags: throwAnyErrors(GET("/tags")),

}),

);

};

You might notice that we extracted the error handling into a generic function throwAnyErrors. It looks pretty useful, so we might want to reuse it later, but for now let’s just keep an eye on it.

Now, to the list of tags. It needs to be interactive — clicking on a tag should make that tag selected. By Remix convention, we will use the URL search parameters as our storage for the selected tag. Let the browser take care of storage while we focus on more important things.

Update pages/feed/ui/FeedPage.tsx with the following code:

import { Form, useLoaderData } from "@remix-run/react";

import { ExistingSearchParams } from "remix-utils/existing-search-params";

import type { loader } from "../api/loader";

import { ArticlePreview } from "./ArticlePreview";

export function FeedPage() {

const { articles, tags } = useLoaderData<typeof loader>();

return (

<div className="home-page">

<div className="banner">

<div className="container">

<h1 className="logo-font">conduit</h1>

<p>A place to share your knowledge.</p>

</div>

</div>

<div className="container page">

<div className="row">

<div className="col-md-9">

{articles.articles.map((article) => (

<ArticlePreview key={article.slug} article={article} />

))}

</div>

<div className="col-md-3">

<div className="sidebar">

<p>Popular Tags</p>

<Form>

<ExistingSearchParams exclude={["tag"]} />

<div className="tag-list">

{tags.tags.map((tag) => (

<button

key={tag}

name="tag"

value={tag}

className="tag-pill tag-default"

>

{tag}

</button>

))}

</div>

</Form>

</div>

</div>

</div>

</div>

</div>

);

}

Then we need to use the tag search parameter in our loader. Change the loader function in pages/feed/api/loader.ts to the following:

import { json, type LoaderFunctionArgs } from "@remix-run/node";

import type { FetchResponse } from "openapi-fetch";

import { promiseHash } from "remix-utils/promise";

import { GET } from "shared/api";

async function throwAnyErrors<T, O, Media extends `${string}/${string}`>(

responsePromise: Promise<FetchResponse<T, O, Media>>,

) {

const { data, error, response } = await responsePromise;

if (error !== undefined) {

throw json(error, { status: response.status });

}

return data as NonNullable<typeof data>;

}

export const loader = async ({ request }: LoaderFunctionArgs) => {

const url = new URL(request.url);

const selectedTag = url.searchParams.get("tag") ?? undefined;

return json(

await promiseHash({

articles: throwAnyErrors(

GET("/articles", { params: { query: { tag: selectedTag } } }),

),

tags: throwAnyErrors(GET("/tags")),

}),

);

};

That’s it, no model segment necessary. Remix is pretty neat.

Pagination

In a similar fashion, we can implement the pagination. Feel free to give it a shot yourself or just copy the code below. There’s no one to judge you anyway.

import { json, type LoaderFunctionArgs } from "@remix-run/node";

import type { FetchResponse } from "openapi-fetch";

import { promiseHash } from "remix-utils/promise";

import { GET } from "shared/api";

async function throwAnyErrors<T, O, Media extends `${string}/${string}`>(

responsePromise: Promise<FetchResponse<T, O, Media>>,

) {

const { data, error, response } = await responsePromise;

if (error !== undefined) {

throw json(error, { status: response.status });

}

return data as NonNullable<typeof data>;

}

/** Amount of articles on one page. */

export const LIMIT = 20;

export const loader = async ({ request }: LoaderFunctionArgs) => {

const url = new URL(request.url);

const selectedTag = url.searchParams.get("tag") ?? undefined;

const page = parseInt(url.searchParams.get("page") ?? "", 10);

return json(

await promiseHash({

articles: throwAnyErrors(

GET("/articles", {

params: {

query: {

tag: selectedTag,

limit: LIMIT,

offset: !Number.isNaN(page) ? page * LIMIT : undefined,

},

},

}),

),

tags: throwAnyErrors(GET("/tags")),

}),

);

};

import { Form, useLoaderData, useSearchParams } from "@remix-run/react";

import { ExistingSearchParams } from "remix-utils/existing-search-params";

import { LIMIT, type loader } from "../api/loader";

import { ArticlePreview } from "./ArticlePreview";

export function FeedPage() {

const [searchParams] = useSearchParams();

const { articles, tags } = useLoaderData<typeof loader>();

const pageAmount = Math.ceil(articles.articlesCount / LIMIT);

const currentPage = parseInt(searchParams.get("page") ?? "1", 10);

return (

<div className="home-page">

<div className="banner">

<div className="container">

<h1 className="logo-font">conduit</h1>

<p>A place to share your knowledge.</p>

</div>

</div>

<div className="container page">

<div className="row">

<div className="col-md-9">

{articles.articles.map((article) => (

<ArticlePreview key={article.slug} article={article} />

))}

<Form>

<ExistingSearchParams exclude={["page"]} />

<ul className="pagination">

{Array(pageAmount)

.fill(null)

.map((_, index) =>

index + 1 === currentPage ? (

<li key={index} className="page-item active">

<span className="page-link">{index + 1}</span>

</li>

) : (

<li key={index} className="page-item">

<button

className="page-link"

name="page"

value={index + 1}

>

{index + 1}

</button>

</li>

),

)}

</ul>

</Form>

</div>

<div className="col-md-3">

<div className="sidebar">

<p>Popular Tags</p>

<Form>

<ExistingSearchParams exclude={["tag", "page"]} />

<div className="tag-list">

{tags.tags.map((tag) => (

<button

key={tag}

name="tag"

value={tag}

className="tag-pill tag-default"

>

{tag}

</button>

))}

</div>

</Form>

</div>

</div>

</div>

</div>

</div>

);

}

So that’s also done. There’s also the tab list that can be similarly implemented, but let’s hold on to that until we implement authentication. Speaking of which!

Authentication

Authentication involves two pages — one to login and another to register. They are mostly the same, so it makes sense to keep them in the same slice, sign-in, so that they can reuse code if needed.

Create RegisterPage.tsx in the ui segment of pages/sign-in with the following content:

import { Form, Link, useActionData } from "@remix-run/react";

import type { register } from "../api/register";

export function RegisterPage() {

const registerData = useActionData<typeof register>();

return (

<div className="auth-page">

<div className="container page">

<div className="row">

<div className="col-md-6 offset-md-3 col-xs-12">

<h1 className="text-xs-center">Sign up</h1>

<p className="text-xs-center">

<Link to="/login">Have an account?</Link>

</p>

{registerData?.error && (

<ul className="error-messages">

{registerData.error.errors.body.map((error) => (

<li key={error}>{error}</li>

))}

</ul>

)}

<Form method="post">

<fieldset className="form-group">

<input

className="form-control form-control-lg"

type="text"

name="username"

placeholder="Username"

/>

</fieldset>

<fieldset className="form-group">

<input

className="form-control form-control-lg"

type="text"

name="email"

placeholder="Email"

/>

</fieldset>

<fieldset className="form-group">

<input

className="form-control form-control-lg"

type="password"

name="password"

placeholder="Password"

/>

</fieldset>

<button className="btn btn-lg btn-primary pull-xs-right">

Sign up

</button>

</Form>

</div>

</div>

</div>

</div>

);

}

We have a broken import to fix now. It involves a new segment, so create that:

npx fsd pages sign-in -s api

However, before we can implement the backend part of registering, we need some infrastructure code for Remix to handle sessions. That goes to Shared, in case any other page needs it.

Put the following code in shared/api/auth.server.ts. This is highly Remix-specific, so don’t worry too much about it, just copy-paste:

import { createCookieSessionStorage, redirect } from "@remix-run/node";

import invariant from "tiny-invariant";

import type { User } from "./models";

invariant(

process.env.SESSION_SECRET,

"SESSION_SECRET must be set for authentication to work",

);

const sessionStorage = createCookieSessionStorage<{

user: User;

}>({

cookie: {

name: "__session",

httpOnly: true,

path: "/",

sameSite: "lax",

secrets: [process.env.SESSION_SECRET],

secure: process.env.NODE_ENV === "production",

},

});

export async function createUserSession({

request,

user,

redirectTo,

}: {

request: Request;

user: User;

redirectTo: string;

}) {

const cookie = request.headers.get("Cookie");

const session = await sessionStorage.getSession(cookie);

session.set("user", user);

return redirect(redirectTo, {

headers: {

"Set-Cookie": await sessionStorage.commitSession(session, {

maxAge: 60 * 60 * 24 * 7, // 7 days

}),

},

});

}

export async function getUserFromSession(request: Request) {

const cookie = request.headers.get("Cookie");

const session = await sessionStorage.getSession(cookie);

return session.get("user") ?? null;

}

export async function requireUser(request: Request) {

const user = await getUserFromSession(request);

if (user === null) {

throw redirect("/login");

}

return user;

}

And also export the User model from the models.ts file right next to it:

import type { components } from "./v1";

export type Article = components["schemas"]["Article"];

export type User = components["schemas"]["User"];

Before this code can work, the SESSION_SECRET environment variable needs to be set. Create a file called .env in the root of the project, write SESSION_SECRET= and then mash some keys on your keyboard to create a long random string. You should get something like this:

SESSION_SECRET=dontyoudarecopypastethis

Finally, add some exports to the public API to make use of this code:

export { GET, POST, PUT, DELETE } from "./client";

export type { Article } from "./models";

export { createUserSession, getUserFromSession, requireUser } from "./auth.server";

Now we can write the code that will talk to the RealWorld backend to actually do the registration. We will keep that in pages/sign-in/api. Create a file called register.ts and put the following code inside:

import { json, type ActionFunctionArgs } from "@remix-run/node";

import { POST, createUserSession } from "shared/api";

export const register = async ({ request }: ActionFunctionArgs) => {

const formData = await request.formData();

const username = formData.get("username")?.toString() ?? "";

const email = formData.get("email")?.toString() ?? "";

const password = formData.get("password")?.toString() ?? "";

const { data, error } = await POST("/users", {

body: { user: { email, password, username } },

});

if (error) {

return json({ error }, { status: 400 });

} else {

return createUserSession({

request: request,

user: data.user,

redirectTo: "/",

});

}

};

export { RegisterPage } from './ui/RegisterPage';

export { register } from './api/register';

Almost done! Just need to connect the page and action to the /register route. Create register.tsx in app/routes:

import { RegisterPage, register } from "pages/sign-in";

export { register as action };

export default RegisterPage;

Now if you go to http://localhost:3000/register, you should be able to create a user! The rest of the application won’t react to this yet, we’ll address that momentarily.

In a very similar way, we can implement the login page. Give it a try or just grab the code and move on:

import { json, type ActionFunctionArgs } from "@remix-run/node";

import { POST, createUserSession } from "shared/api";

export const signIn = async ({ request }: ActionFunctionArgs) => {

const formData = await request.formData();

const email = formData.get("email")?.toString() ?? "";

const password = formData.get("password")?.toString() ?? "";

const { data, error } = await POST("/users/login", {

body: { user: { email, password } },

});

if (error) {

return json({ error }, { status: 400 });

} else {

return createUserSession({

request: request,

user: data.user,

redirectTo: "/",

});

}

};

import { Form, Link, useActionData } from "@remix-run/react";

import type { signIn } from "../api/sign-in";

export function SignInPage() {

const signInData = useActionData<typeof signIn>();

return (

<div className="auth-page">

<div className="container page">

<div className="row">

<div className="col-md-6 offset-md-3 col-xs-12">

<h1 className="text-xs-center">Sign in</h1>

<p className="text-xs-center">

<Link to="/register">Need an account?</Link>

</p>

{signInData?.error && (

<ul className="error-messages">

{signInData.error.errors.body.map((error) => (

<li key={error}>{error}</li>

))}

</ul>

)}

<Form method="post">

<fieldset className="form-group">

<input

className="form-control form-control-lg"

name="email"

type="text"

placeholder="Email"

/>

</fieldset>

<fieldset className="form-group">

<input

className="form-control form-control-lg"

name="password"

type="password"

placeholder="Password"

/>

</fieldset>

<button className="btn btn-lg btn-primary pull-xs-right">

Sign in

</button>

</Form>

</div>

</div>

</div>

</div>

);

}

export { RegisterPage } from './ui/RegisterPage';

export { register } from './api/register';

export { SignInPage } from './ui/SignInPage';

export { signIn } from './api/sign-in';

import { SignInPage, signIn } from "pages/sign-in";

export { signIn as action };

export default SignInPage;

Now let’s give the users a way to actually get to these pages.

Header

As we discussed in part 1, the app header is commonly placed either in Widgets or in Shared. We will put it in Shared because it’s very simple and all the business logic can be kept outside of it. Let’s create a place for it:

npx fsd shared ui

Now create shared/ui/Header.tsx with the following contents:

import { useContext } from "react";

import { Link, useLocation } from "@remix-run/react";

import { CurrentUser } from "../api/currentUser";

export function Header() {

const currentUser = useContext(CurrentUser);

const { pathname } = useLocation();

return (

<nav className="navbar navbar-light">

<div className="container">

<Link className="navbar-brand" to="/" prefetch="intent">

conduit

</Link>

<ul className="nav navbar-nav pull-xs-right">

<li className="nav-item">

<Link

prefetch="intent"

className={`nav-link ${pathname == "/" ? "active" : ""}`}

to="/"

>

Home

</Link>

</li>

{currentUser == null ? (

<>

<li className="nav-item">

<Link

prefetch="intent"

className={`nav-link ${pathname == "/login" ? "active" : ""}`}

to="/login"

>

Sign in

</Link>

</li>

<li className="nav-item">

<Link

prefetch="intent"

className={`nav-link ${pathname == "/register" ? "active" : ""}`}

to="/register"

>

Sign up

</Link>

</li>

</>

) : (

<>

<li className="nav-item">

<Link

prefetch="intent"

className={`nav-link ${pathname == "/editor" ? "active" : ""}`}

to="/editor"

>

<i className="ion-compose"></i> New Article{" "}

</Link>

</li>

<li className="nav-item">

<Link

prefetch="intent"

className={`nav-link ${pathname == "/settings" ? "active" : ""}`}

to="/settings"

>

{" "}

<i className="ion-gear-a"></i> Settings{" "}

</Link>

</li>

<li className="nav-item">

<Link

prefetch="intent"

className={`nav-link ${pathname.includes("/profile") ? "active" : ""}`}

to={`/profile/${currentUser.username}`}

>

{currentUser.image && (

<img

width={25}

height={25}

src={currentUser.image}

className="user-pic"

alt=""

/>

)}

{currentUser.username}

</Link>

</li>

</>

)}

</ul>

</div>

</nav>

);

}

Export this component from shared/ui:

export { Header } from "./Header";

In the header, we rely on the context that’s kept in shared/api. Create that as well:

import { createContext } from "react";

import type { User } from "./models";

export const CurrentUser = createContext<User | null>(null);

export { GET, POST, PUT, DELETE } from "./client";

export type { Article } from "./models";

export { createUserSession, getUserFromSession, requireUser } from "./auth.server";

export { CurrentUser } from "./currentUser";

Now let’s add the header to the page. We want it to be on every single page, so it makes sense to simply add it to the root route and wrap the outlet (the place where the page will be rendered) with the CurrentUser context provider. This way our entire app and also the header has access to the current user object. We will also add a loader to actually obtain the current user object from cookies. Drop the following into app/root.tsx:

import { cssBundleHref } from "@remix-run/css-bundle";

import type { LinksFunction, LoaderFunctionArgs } from "@remix-run/node";

import {

Links,

LiveReload,

Meta,

Outlet,

Scripts,

ScrollRestoration,

useLoaderData,

} from "@remix-run/react";

import { Header } from "shared/ui";

import { getUserFromSession, CurrentUser } from "shared/api";

export const links: LinksFunction = () => [

...(cssBundleHref ? [{ rel: "stylesheet", href: cssBundleHref }] : []),

];

export const loader = ({ request }: LoaderFunctionArgs) =>

getUserFromSession(request);

export default function App() {

const user = useLoaderData<typeof loader>();

return (

<html lang="en">

<head>

<meta charSet="utf-8" />

<meta name="viewport" content="width=device-width, initial-scale=1" />

<Meta />

<Links />

<link

href="//code.ionicframework.com/ionicons/2.0.1/css/ionicons.min.css"

rel="stylesheet"

type="text/css"

/>

<link

href="//fonts.googleapis.com/css?family=Titillium+Web:700|Source+Serif+Pro:400,700|Merriweather+Sans:400,700|Source+Sans+Pro:400,300,600,700,300italic,400italic,600italic,700italic"

rel="stylesheet"

type="text/css"

/>

<link rel="stylesheet" href="//demo.productionready.io/main.css" />

<style>{`

button {

border: 0;

}

`}</style>

</head>

<body>

<CurrentUser.Provider value={user}>

<Header />

<Outlet />

</CurrentUser.Provider>

<ScrollRestoration />

<Scripts />

<LiveReload />

</body>

</html>

);

}

At this point, you should end up with the following on the home page:

Tabs

Now that we can detect the authentication state, let’s also quickly implement the tabs and post likes to be done with the feed page. We need another form, but this page file is getting kind of large, so let’s move these forms into adjacent files. We will create Tabs.tsx, PopularTags.tsx, and Pagination.tsx with the following content:

import { useContext } from "react";

import { Form, useSearchParams } from "@remix-run/react";

import { CurrentUser } from "shared/api";

export function Tabs() {

const [searchParams] = useSearchParams();

const currentUser = useContext(CurrentUser);

return (

<Form>

<div className="feed-toggle">

<ul className="nav nav-pills outline-active">

{currentUser !== null && (

<li className="nav-item">

<button

name="source"

value="my-feed"

className={`nav-link ${searchParams.get("source") === "my-feed" ? "active" : ""}`}

>

Your Feed

</button>

</li>

)}

<li className="nav-item">

<button

className={`nav-link ${searchParams.has("tag") || searchParams.has("source") ? "" : "active"}`}

>

Global Feed

</button>

</li>

{searchParams.has("tag") && (

<li className="nav-item">

<span className="nav-link active">

<i className="ion-pound"></i> {searchParams.get("tag")}

</span>

</li>

)}

</ul>

</div>

</Form>

);

}

import { Form, useLoaderData } from "@remix-run/react";

import { ExistingSearchParams } from "remix-utils/existing-search-params";

import type { loader } from "../api/loader";

export function PopularTags() {

const { tags } = useLoaderData<typeof loader>();

return (

<div className="sidebar">

<p>Popular Tags</p>

<Form>

<ExistingSearchParams exclude={["tag", "page", "source"]} />

<div className="tag-list">

{tags.tags.map((tag) => (

<button

key={tag}

name="tag"

value={tag}

className="tag-pill tag-default"

>

{tag}

</button>

))}

</div>

</Form>

</div>

);

}

import { Form, useLoaderData, useSearchParams } from "@remix-run/react";

import { ExistingSearchParams } from "remix-utils/existing-search-params";

import { LIMIT, type loader } from "../api/loader";

export function Pagination() {

const [searchParams] = useSearchParams();

const { articles } = useLoaderData<typeof loader>();

const pageAmount = Math.ceil(articles.articlesCount / LIMIT);

const currentPage = parseInt(searchParams.get("page") ?? "1", 10);

return (

<Form>

<ExistingSearchParams exclude={["page"]} />

<ul className="pagination">

{Array(pageAmount)

.fill(null)

.map((_, index) =>

index + 1 === currentPage ? (

<li key={index} className="page-item active">

<span className="page-link">{index + 1}</span>

</li>

) : (

<li key={index} className="page-item">

<button className="page-link" name="page" value={index + 1}>

{index + 1}

</button>

</li>

),

)}

</ul>

</Form>

);

}

And now we can significantly simplify the feed page itself:

import { useLoaderData } from "@remix-run/react";

import type { loader } from "../api/loader";

import { ArticlePreview } from "./ArticlePreview";

import { Tabs } from "./Tabs";

import { PopularTags } from "./PopularTags";

import { Pagination } from "./Pagination";

export function FeedPage() {

const { articles } = useLoaderData<typeof loader>();

return (

<div className="home-page">

<div className="banner">

<div className="container">

<h1 className="logo-font">conduit</h1>

<p>A place to share your knowledge.</p>

</div>

</div>

<div className="container page">

<div className="row">

<div className="col-md-9">

<Tabs />

{articles.articles.map((article) => (

<ArticlePreview key={article.slug} article={article} />

))}

<Pagination />

</div>

<div className="col-md-3">

<PopularTags />

</div>

</div>

</div>

</div>

);

}

We also need to account for the new tab in the loader function:

import { json, type LoaderFunctionArgs } from "@remix-run/node";

import type { FetchResponse } from "openapi-fetch";

import { promiseHash } from "remix-utils/promise";

import { GET, requireUser } from "shared/api";

async function throwAnyErrors<T, O, Media extends `${string}/${string}`>(

responsePromise: Promise<FetchResponse<T, O, Media>>,

) {

/* unchanged */

}

/** Amount of articles on one page. */

export const LIMIT = 20;

export const loader = async ({ request }: LoaderFunctionArgs) => {

const url = new URL(request.url);

const selectedTag = url.searchParams.get("tag") ?? undefined;

const page = parseInt(url.searchParams.get("page") ?? "", 10);

if (url.searchParams.get("source") === "my-feed") {

const userSession = await requireUser(request);

return json(

await promiseHash({

articles: throwAnyErrors(

GET("/articles/feed", {

params: {

query: {

limit: LIMIT,

offset: !Number.isNaN(page) ? page * LIMIT : undefined,

},

},

headers: { Authorization: `Token ${userSession.token}` },

}),

),

tags: throwAnyErrors(GET("/tags")),

}),

);

}

return json(

await promiseHash({

articles: throwAnyErrors(

GET("/articles", {

params: {

query: {

tag: selectedTag,

limit: LIMIT,

offset: !Number.isNaN(page) ? page * LIMIT : undefined,

},

},

}),

),

tags: throwAnyErrors(GET("/tags")),

}),

);

};

Before we leave the feed page, let’s add some code that handles likes to posts. Change your ArticlePreview.tsx to the following:

import { Form, Link } from "@remix-run/react";

import type { Article } from "shared/api";

interface ArticlePreviewProps {

article: Article;

}

export function ArticlePreview({ article }: ArticlePreviewProps) {

return (

<div className="article-preview">

<div className="article-meta">

<Link to={`/profile/${article.author.username}`} prefetch="intent">

<img src={article.author.image} alt="" />

</Link>

<div className="info">

<Link

to={`/profile/${article.author.username}`}

className="author"

prefetch="intent"

>

{article.author.username}

</Link>

<span className="date" suppressHydrationWarning>

{new Date(article.createdAt).toLocaleDateString(undefined, {

dateStyle: "long",

})}

</span>

</div>

<Form

method="post"

action={`/article/${article.slug}`}

preventScrollReset

>

<button

name="_action"

value={article.favorited ? "unfavorite" : "favorite"}

className={`btn ${article.favorited ? "btn-primary" : "btn-outline-primary"} btn-sm pull-xs-right`}

>

<i className="ion-heart"></i> {article.favoritesCount}

</button>

</Form>

</div>

<Link

to={`/article/${article.slug}`}

className="preview-link"

prefetch="intent"

>

<h1>{article.title}</h1>

<p>{article.description}</p>

<span>Read more...</span>

<ul className="tag-list">

{article.tagList.map((tag) => (

<li key={tag} className="tag-default tag-pill tag-outline">

{tag}

</li>

))}

</ul>

</Link>

</div>

);

}

This code will send a POST request to /article/:slug with _action=favorite to mark the article as favorite. It won’t work yet, but as we start working on the article reader, we will implement this too.

And with that we are officially done with the feed! Yay!

Article reader

First, we need data. Let’s create a loader:

npx fsd pages article-read -s api

import { json, type LoaderFunctionArgs } from "@remix-run/node";

import invariant from "tiny-invariant";

import type { FetchResponse } from "openapi-fetch";

import { promiseHash } from "remix-utils/promise";

import { GET, getUserFromSession } from "shared/api";

async function throwAnyErrors<T, O, Media extends `${string}/${string}`>(

responsePromise: Promise<FetchResponse<T, O, Media>>,

) {

const { data, error, response } = await responsePromise;

if (error !== undefined) {

throw json(error, { status: response.status });

}

return data as NonNullable<typeof data>;

}

export const loader = async ({ request, params }: LoaderFunctionArgs) => {

invariant(params.slug, "Expected a slug parameter");

const currentUser = await getUserFromSession(request);

const authorization = currentUser

? { Authorization: `Token ${currentUser.token}` }

: undefined;

return json(

await promiseHash({

article: throwAnyErrors(

GET("/articles/{slug}", {

params: {

path: { slug: params.slug },

},

headers: authorization,

}),

),

comments: throwAnyErrors(

GET("/articles/{slug}/comments", {

params: {

path: { slug: params.slug },

},

headers: authorization,

}),

),

}),

);

};

export { loader } from "./api/loader";

Now we can connect it to the route /article/:slug by creating the a route file called article.$slug.tsx:

export { loader } from "pages/article-read";

The page itself consists of three main blocks — the article header with actions (repeated twice), the article body, and the comments section. This is the markup for the page, it’s not particularly interesting:

import { useLoaderData } from "@remix-run/react";

import type { loader } from "../api/loader";

import { ArticleMeta } from "./ArticleMeta";

import { Comments } from "./Comments";

export function ArticleReadPage() {

const { article } = useLoaderData<typeof loader>();

return (

<div className="article-page">

<div className="banner">

<div className="container">

<h1>{article.article.title}</h1>

<ArticleMeta />

</div>

</div>

<div className="container page">

<div className="row article-content">

<div className="col-md-12">

<p>{article.article.body}</p>

<ul className="tag-list">

{article.article.tagList.map((tag) => (

<li className="tag-default tag-pill tag-outline" key={tag}>

{tag}

</li>

))}

</ul>

</div>

</div>

<hr />

<div className="article-actions">

<ArticleMeta />

</div>

<div className="row">

<Comments />

</div>

</div>

</div>

);

}

What’s more interesting is the ArticleMeta and Comments. They contain write operations such as liking an article, leaving a comment, etc. To get them to work, we first need to implement the backend part. Create action.ts in the api segment of the page:

import { redirect, type ActionFunctionArgs } from "@remix-run/node";

import { namedAction } from "remix-utils/named-action";

import { redirectBack } from "remix-utils/redirect-back";

import invariant from "tiny-invariant";

import { DELETE, POST, requireUser } from "shared/api";

export const action = async ({ request, params }: ActionFunctionArgs) => {

const currentUser = await requireUser(request);

const authorization = { Authorization: `Token ${currentUser.token}` };

const formData = await request.formData();

return namedAction(formData, {

async delete() {

invariant(params.slug, "Expected a slug parameter");

await DELETE("/articles/{slug}", {

params: { path: { slug: params.slug } },

headers: authorization,

});

return redirect("/");

},

async favorite() {

invariant(params.slug, "Expected a slug parameter");

await POST("/articles/{slug}/favorite", {

params: { path: { slug: params.slug } },

headers: authorization,

});

return redirectBack(request, { fallback: "/" });

},

async unfavorite() {

invariant(params.slug, "Expected a slug parameter");

await DELETE("/articles/{slug}/favorite", {

params: { path: { slug: params.slug } },

headers: authorization,

});

return redirectBack(request, { fallback: "/" });

},

async createComment() {

invariant(params.slug, "Expected a slug parameter");

const comment = formData.get("comment");

invariant(typeof comment === "string", "Expected a comment parameter");

await POST("/articles/{slug}/comments", {

params: { path: { slug: params.slug } },

headers: { ...authorization, "Content-Type": "application/json" },

body: { comment: { body: comment } },

});

return redirectBack(request, { fallback: "/" });

},

async deleteComment() {

invariant(params.slug, "Expected a slug parameter");

const commentId = formData.get("id");

invariant(typeof commentId === "string", "Expected an id parameter");

const commentIdNumeric = parseInt(commentId, 10);

invariant(

!Number.isNaN(commentIdNumeric),

"Expected a numeric id parameter",

);

await DELETE("/articles/{slug}/comments/{id}", {

params: { path: { slug: params.slug, id: commentIdNumeric } },

headers: authorization,

});

return redirectBack(request, { fallback: "/" });

},

async followAuthor() {

const authorUsername = formData.get("username");

invariant(

typeof authorUsername === "string",

"Expected a username parameter",

);

await POST("/profiles/{username}/follow", {

params: { path: { username: authorUsername } },

headers: authorization,

});

return redirectBack(request, { fallback: "/" });

},

async unfollowAuthor() {

const authorUsername = formData.get("username");

invariant(

typeof authorUsername === "string",

"Expected a username parameter",

);

await DELETE("/profiles/{username}/follow", {

params: { path: { username: authorUsername } },

headers: authorization,

});

return redirectBack(request, { fallback: "/" });

},

});

};

Export that from the slice and then from the route. While we’re at it, let’s also connect the page itself:

export { ArticleReadPage } from "./ui/ArticleReadPage";

export { loader } from "./api/loader";

export { action } from "./api/action";

import { ArticleReadPage } from "pages/article-read";

export { loader, action } from "pages/article-read";

export default ArticleReadPage;

Now, even though we haven’t implemented the like button on the reader page yet, the like button in the feed will start working! That’s because it’s been sending “like” requests to this route. Give that a try.

ArticleMeta and Comments are, again, a bunch of forms. We’ve done this before, let’s grab their code and move on:

import { Form, Link, useLoaderData } from "@remix-run/react";

import { useContext } from "react";

import { CurrentUser } from "shared/api";

import type { loader } from "../api/loader";

export function ArticleMeta() {

const currentUser = useContext(CurrentUser);

const { article } = useLoaderData<typeof loader>();

return (

<Form method="post">

<div className="article-meta">

<Link

prefetch="intent"

to={`/profile/${article.article.author.username}`}

>

<img src={article.article.author.image} alt="" />

</Link>

<div className="info">

<Link

prefetch="intent"

to={`/profile/${article.article.author.username}`}

className="author"

>

{article.article.author.username}

</Link>

<span className="date">{article.article.createdAt}</span>

</div>

{article.article.author.username == currentUser?.username ? (

<>

<Link

prefetch="intent"

to={`/editor/${article.article.slug}`}

className="btn btn-sm btn-outline-secondary"

>

<i className="ion-edit"></i> Edit Article

</Link>

<button

name="_action"

value="delete"

className="btn btn-sm btn-outline-danger"

>

<i className="ion-trash-a"></i> Delete Article

</button>

</>

) : (

<>

<input

name="username"

value={article.article.author.username}

type="hidden"

/>

<button

name="_action"

value={

article.article.author.following

? "unfollowAuthor"

: "followAuthor"

}

className={`btn btn-sm ${article.article.author.following ? "btn-secondary" : "btn-outline-secondary"}`}

>

<i className="ion-plus-round"></i>

{" "}

{article.article.author.following

? "Unfollow"

: "Follow"}{" "}

{article.article.author.username}

</button>

<button

name="_action"

value={article.article.favorited ? "unfavorite" : "favorite"}

className={`btn btn-sm ${article.article.favorited ? "btn-primary" : "btn-outline-primary"}`}

>

<i className="ion-heart"></i>

{article.article.favorited

? "Unfavorite"

: "Favorite"}{" "}

Post{" "}

<span className="counter">

({article.article.favoritesCount})

</span>

</button>

</>

)}

</div>

</Form>

);

}

import { useContext } from "react";

import { Form, Link, useLoaderData } from "@remix-run/react";

import { CurrentUser } from "shared/api";

import type { loader } from "../api/loader";

export function Comments() {

const { comments } = useLoaderData<typeof loader>();

const currentUser = useContext(CurrentUser);

return (

<div className="col-xs-12 col-md-8 offset-md-2">

{currentUser !== null ? (

<Form

preventScrollReset={true}

method="post"

className="card comment-form"

>

<div className="card-block">

<textarea

required

className="form-control"

name="comment"

placeholder="Write a comment..."

rows={3}

></textarea>

</div>

<div className="card-footer">

<img

src={currentUser.image}

className="comment-author-img"

alt=""

/>

<button

className="btn btn-sm btn-primary"

name="_action"

value="createComment"

>

Post Comment

</button>

</div>

</Form>

) : (

<div className="row">

<div className="col-xs-12 col-md-8 offset-md-2">

<p>

<Link to="/login">Sign in</Link>

or

<Link to="/register">Sign up</Link>

to add comments on this article.

</p>

</div>

</div>

)}

{comments.comments.map((comment) => (

<div className="card" key={comment.id}>

<div className="card-block">

<p className="card-text">{comment.body}</p>

</div>

<div className="card-footer">

<Link

to={`/profile/${comment.author.username}`}

className="comment-author"

>

<img

src={comment.author.image}

className="comment-author-img"

alt=""

/>

</Link>

<Link

to={`/profile/${comment.author.username}`}

className="comment-author"

>

{comment.author.username}

</Link>

<span className="date-posted">{comment.createdAt}</span>

{comment.author.username === currentUser?.username && (

<span className="mod-options">

<Form method="post" preventScrollReset={true}>

<input type="hidden" name="id" value={comment.id} />

<button

name="_action"

value="deleteComment"

style={{

border: "none",

outline: "none",

backgroundColor: "transparent",

}}

>

<i className="ion-trash-a"></i>

</button>

</Form>

</span>

)}

</div>

</div>

))}

</div>

);

}

And with that our article reader is also complete! The buttons to follow the author, like a post, and leave a comment should now function as expected.

Article editor

This is the last page that we will cover in this tutorial, and the most interesting part here is how we’re going to validate form data.

The page itself, article-edit/ui/ArticleEditPage.tsx, will be quite simple, extra complexity stowed away into two other components:

import { Form, useLoaderData } from "@remix-run/react";

import type { loader } from "../api/loader";

import { TagsInput } from "./TagsInput";

import { FormErrors } from "./FormErrors";

export function ArticleEditPage() {

const article = useLoaderData<typeof loader>();

return (

<div className="editor-page">

<div className="container page">

<div className="row">

<div className="col-md-10 offset-md-1 col-xs-12">

<FormErrors />

<Form method="post">

<fieldset>

<fieldset className="form-group">

<input

type="text"

className="form-control form-control-lg"

name="title"

placeholder="Article Title"

defaultValue={article.article?.title}

/>

</fieldset>

<fieldset className="form-group">

<input

type="text"

className="form-control"

name="description"

placeholder="What's this article about?"

defaultValue={article.article?.description}

/>

</fieldset>

<fieldset className="form-group">

<textarea

className="form-control"

name="body"

rows={8}

placeholder="Write your article (in markdown)"

defaultValue={article.article?.body}

></textarea>

</fieldset>

<fieldset className="form-group">

<TagsInput

name="tags"

defaultValue={article.article?.tagList ?? []}

/>

</fieldset>

<button className="btn btn-lg pull-xs-right btn-primary">

Publish Article

</button>

</fieldset>

</Form>

</div>

</div>

</div>

</div>

);

}

This page gets the current article (unless we’re writing from scratch) and fills in the corresponding form fields. We’ve seen this before. The interesting part is FormErrors, because it will receive the validation result and display it to the user. Let’s take a look:

import { useActionData } from "@remix-run/react";

import type { action } from "../api/action";

export function FormErrors() {

const actionData = useActionData<typeof action>();

return actionData?.errors != null ? (

<ul className="error-messages">

{actionData.errors.map((error) => (

<li key={error}>{error}</li>

))}

</ul>

) : null;

}

Here we are assuming that our action will return the errors field, an array of human-readable error messages. We will get to the action shortly.

Another component is the tags input. It’s just a plain input field with an additional preview of chosen tags. Not much to see here:

import { useEffect, useRef, useState } from "react";

export function TagsInput({

name,

defaultValue,

}: {

name: string;

defaultValue?: Array<string>;

}) {

const [tagListState, setTagListState] = useState(defaultValue ?? []);

function removeTag(tag: string): void {

const newTagList = tagListState.filter((t) => t !== tag);

setTagListState(newTagList);

}

const tagsInput = useRef<HTMLInputElement>(null);

useEffect(() => {

tagsInput.current && (tagsInput.current.value = tagListState.join(","));

}, [tagListState]);

return (

<>

<input

type="text"

className="form-control"

id="tags"

name={name}

placeholder="Enter tags"

defaultValue={tagListState.join(",")}

onChange={(e) =>

setTagListState(e.target.value.split(",").filter(Boolean))

}

/>

<div className="tag-list">

{tagListState.map((tag) => (

<span className="tag-default tag-pill" key={tag}>

<i

className="ion-close-round"

role="button"

tabIndex={0}

onKeyDown={(e) =>

[" ", "Enter"].includes(e.key) && removeTag(tag)

}

onClick={() => removeTag(tag)}

></i>{" "}

{tag}

</span>

))}

</div>

</>

);

}

Now, for the API part. The loader should look at the URL, and if it contains an article slug, that means we’re editing an existing article, and its data should be loaded. Otherwise, return nothing. Let’s create that loader:

import { json, type LoaderFunctionArgs } from "@remix-run/node";

import type { FetchResponse } from "openapi-fetch";

import { GET, requireUser } from "shared/api";

async function throwAnyErrors<T, O, Media extends `${string}/${string}`>(

responsePromise: Promise<FetchResponse<T, O, Media>>,

) {

const { data, error, response } = await responsePromise;

if (error !== undefined) {

throw json(error, { status: response.status });

}

return data as NonNullable<typeof data>;

}

export const loader = async ({ params, request }: LoaderFunctionArgs) => {

const currentUser = await requireUser(request);

if (!params.slug) {

return { article: null };

}

return throwAnyErrors(

GET("/articles/{slug}", {

params: { path: { slug: params.slug } },

headers: { Authorization: `Token ${currentUser.token}` },

}),

);

};

The action will take the new field values, run them through our data schema, and if everything is correct, commit those changes to the backend, either by updating an existing article or creating a new one:

import { json, redirect, type ActionFunctionArgs } from "@remix-run/node";

import { POST, PUT, requireUser } from "shared/api";

import { parseAsArticle } from "../model/parseAsArticle";

export const action = async ({ request, params }: ActionFunctionArgs) => {

try {

const { body, description, title, tags } = parseAsArticle(

await request.formData(),

);

const tagList = tags?.split(",") ?? [];

const currentUser = await requireUser(request);

const payload = {

body: {

article: {

title,

description,

body,

tagList,

},

},

headers: { Authorization: `Token ${currentUser.token}` },

};

const { data, error } = await (params.slug

? PUT("/articles/{slug}", {

params: { path: { slug: params.slug } },

...payload,

})

: POST("/articles", payload));

if (error) {

return json({ errors: error }, { status: 422 });

}

return redirect(`/article/${data.article.slug ?? ""}`);

} catch (errors) {

return json({ errors }, { status: 400 });

}

};

The schema doubles as a parsing function for FormData, which allows us to conveniently get the clean fields or just throw the errors to handle at the end. Here’s how that parsing function could look:

export function parseAsArticle(data: FormData) {

const errors = [];

const title = data.get("title");

if (typeof title !== "string" || title === "") {

errors.push("Give this article a title");

}

const description = data.get("description");

if (typeof description !== "string" || description === "") {

errors.push("Describe what this article is about");

}

const body = data.get("body");

if (typeof body !== "string" || body === "") {

errors.push("Write the article itself");

}

const tags = data.get("tags");

if (typeof tags !== "string") {

errors.push("The tags must be a string");

}

if (errors.length > 0) {

throw errors;

}

return { title, description, body, tags: data.get("tags") ?? "" } as {

title: string;

description: string;

body: string;

tags: string;

};

}

Arguably, it’s a bit lengthy and repetitive, but that’s the price we pay for human-readable errors. This could also be a Zod schema, for example, but then we would have to render error messages on the frontend, and this form is not worth the complication.

One last step — connect the page, the loader, and the action to the routes. Since we neatly support both creation and editing, we can export the same thing from both editor._index.tsx and editor.$slug.tsx:

export { ArticleEditPage } from "./ui/ArticleEditPage";

export { loader } from "./api/loader";

export { action } from "./api/action";

import { ArticleEditPage } from "pages/article-edit";

export { loader, action } from "pages/article-edit";

export default ArticleEditPage;

We’re done now! Log in and try creating a new article. Or “forget” to write the article and see the validation kick in.

The profile and settings pages are very similar to the article reader and editor, they are left as an exercise for the reader, that’s you :)