Taming Webpack: A Guide to Modern Architecture

TLDR:

Webpack can feel like a black box once configs grow and boundaries blur. This guide walks through a clean, modern setup—from loaders and plugins to performance tuning and Module Federation—then shows how Feature-Sliced Design keeps your codebase modular, refactor-friendly, and easier to scale.

Webpack is powerful, but a growing webpack config can turn into an opaque build pipeline that slows onboarding, blocks refactors, and inflates bundle size. This guide shows how to build a modern webpack.config.js, reason about webpack loaders and webpack plugins, implement code splitting and tree shaking, and safely adopt Module Federation—then connect it all to a maintainable architecture with Feature-Sliced Design (FSD) from feature-sliced.design.

Mastering webpack.config.js: a modern baseline from scratch

A key principle in software engineering is: complex systems become manageable when you control boundaries and make dependencies explicit. Webpack’s job is to turn a dependency graph into optimized chunks. Your job is to make that graph predictable.

The mental model: from modules to chunks

Webpack builds two related graphs:

• Module graph: every import becomes an edge, and every file is a module (JS, CSS, images via asset modules).

• Chunk graph: modules are grouped into chunks based on entry points, dynamic imports, and optimization rules.

If you keep this model in mind, most “webpack magic” becomes a set of intentional decisions:

- Entry points define starting nodes in the module graph.

- Loaders transform source files into modules webpack can understand.

- Plugins extend the compiler and affect chunking, output, and build lifecycle.

- Optimization shapes the chunk graph for performance and caching.

Step 1: Create a minimal config that you can explain

Start with a config that answers only four questions: where do we start, where do we output, how do we resolve, and how do we build for dev vs prod.

// webpack.config.js

const path = require("path");

module.exports = (env, argv) => {

const isProd = argv.mode === "production";

return {

mode: isProd ? "production" : "development",

entry: {

app: path.resolve(__dirname, "src/app/index.tsx"),

},

output: {

path: path.resolve(__dirname, "dist"),

filename: isProd ? "js/[name].[contenthash:8].js" : "js/[name].js",

chunkFilename: isProd ? "js/[name].[contenthash:8].chunk.js" : "js/[name].chunk.js",

publicPath: "/",

clean: true,

},

resolve: {

extensions: [".ts", ".tsx", ".js", ".jsx", ".json"],

},

};

};

This is intentionally boring. Boring is good.

Step 2: Add JavaScript/TypeScript transformation (Babel or ts-loader)

For most teams, Babel + TypeScript is a balanced setup:

• TypeScript handles typechecking (often in a separate process).

• Babel handles fast transpilation (including React JSX) and targets browsers via @babel/preset-env.

module: {

rules: [

{

test: /\.[jt]sx?$/,

exclude: /node_modules/,

use: {

loader: "babel-loader",

options: {

cacheDirectory: true,

presets: [

["@babel/preset-env", { modules: false }],

["@babel/preset-react", { runtime: "automatic" }],

["@babel/preset-typescript"]

],

},

},

},

],

}

Why modules: false? It keeps ES modules so webpack can do tree shaking and usedExports analysis more effectively.

Typechecking should not block bundling:

• Run tsc --noEmit in CI.

• Optionally run a forked typechecker in dev (fast feedback without slowing rebuilds).

Step 3: Add HTML and environment variables

Most SPAs need an HTML shell and compile-time flags.

plugins: [

new HtmlWebpackPlugin({

template: "public/index.html",

inject: "body",

}),

new DefinePlugin({

__DEV__: JSON.stringify(!isProd),

"process.env.NODE_ENV": JSON.stringify(isProd ? "production" : "development"),

}),

]

DefinePlugin is not runtime env injection. It’s compile-time replacement. Treat it like a public API: keep the surface small and documented.

Step 4: Add CSS with a dev/prod split

CSS processing is a common source of webpack confusion. Keep it explicit:

• In dev, inject styles for fast HMR.

• In prod, extract CSS to separate files for caching.

const cssLoaders = [

isProd ? MiniCssExtractPlugin.loader : "style-loader",

{

loader: "css-loader",

options: {

modules: {

auto: /\.module\.css$/,

localIdentName: isProd ? "[hash:base64:6]" : "[path][name]__[local]",

},

importLoaders: 1,

},

},

"postcss-loader",

];

module: {

rules: [

{ test: /\.css$/, use: cssLoaders },

],

}

plugins: [

...(isProd ? [new MiniCssExtractPlugin({ filename: "css/[name].[contenthash:8].css" })] : []),

]

This gives you CSS Modules for scoped styles and PostCSS for autoprefixing, nesting, and shared utilities.

Step 5: Handle assets the webpack 5 way

Webpack 5 asset modules can replace many file-loader/url-loader cases.

module: {

rules: [

{ test: /\.(png|jpg|jpeg|gif|webp)$/i, type: "asset", parser: { dataUrlCondition: { maxSize: 8 * 1024 } } },

{ test: /\.(svg)$/i, type: "asset/resource" },

{ test: /\.(woff2?|eot|ttf|otf)$/i, type: "asset/resource" },

],

}

Now you’re using webpack’s native asset pipeline with predictable outputs.

Step 6: Set up a productive dev server

Webpack Dev Server is great when configured intentionally:

• SPA routing requires historyApiFallback.

• A stable port and client overlay reduce friction.

• HMR improves iteration speed.

devServer: {

port: 3000,

hot: true,

historyApiFallback: true,

static: { directory: path.resolve(__dirname, "public") },

client: { overlay: { warnings: false, errors: true } },

}

Step 7: Split config by intent, not by file count

As projects grow, “one big config” becomes a coordination bottleneck. A maintainable approach:

• webpack.common.js: shared base.

• webpack.dev.js: dev-only knobs.

• webpack.prod.js: optimization, hashing, extract CSS.

• A tiny webpack.config.js that composes them.

This is not just cleanliness. It reduces accidental coupling between dev and prod behavior.

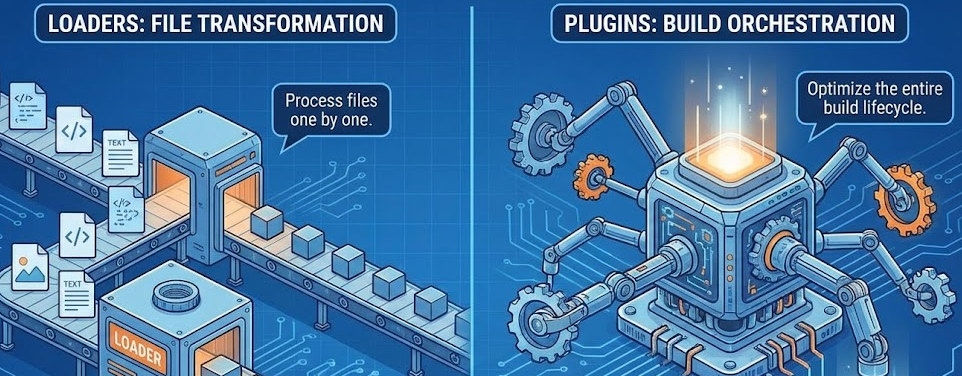

Loaders vs Plugins: the real difference and how to choose

Leading architects suggest a simple rubric: use a loader when you transform a file; use a plugin when you change how webpack builds. That's the 80/20.

A crisp comparison you can apply daily

| Aspect | Loaders | Plugins |

|---|---|---|

| What they act on | A matched file/module (via module.rules) | The whole compilation lifecycle (hooks) |

| Primary job | Transform content (e.g., TS → JS, CSS → JS module) | Extend/alter bundling, chunking, output, and assets |

| Typical examples | babel-loader, css-loader, postcss-loader | HtmlWebpackPlugin, MiniCssExtractPlugin, DefinePlugin |

Loaders are pipelines. Plugins are orchestrators.

Common loader patterns (and why they matter)

JavaScript/TypeScript loaders

Most modern setups choose one of these paths:

• Babel loader: fast transpilation, flexible presets, good ecosystem.

• ts-loader: closer to TypeScript compiler behavior; can be slower.

• SWC loader or esbuild loader: extremely fast, great for large monorepos (trade-offs vary by feature).

Pick based on constraints:

• If rebuild speed is a priority, consider SWC/esbuild.

• If you rely on advanced TypeScript emit behaviors, validate with ts-loader or dedicated tooling.

CSS loaders and the “order problem”

CSS loader order is not arbitrary:

style-loader/ extract loader handles injection/extraction.css-loaderturns CSS into a JS module (and resolves@importandurl()).postcss-loadertransforms CSS (autoprefixer, etc.).- Optional:

sass-loadercompiles Sass to CSS (usually placed after PostCSS, depending on your pipeline needs).

The output becomes part of the module graph, which affects chunking. This is why CSS can change your chunk boundaries.

Asset handling and SVG nuance

SVG can be:

• a file URL (asset/resource)

• an inline data URL (asset/inline)

• a React component (via an SVG-to-JSX loader)

Be explicit in your rules to avoid surprising behavior.

Common plugin patterns (and what they unlock)

Plugins run on webpack’s compiler hooks (Tapable). They enable:

• HTML generation: HtmlWebpackPlugin creates the HTML file(s) and injects scripts.

• CSS extraction: MiniCssExtractPlugin moves CSS to dedicated files.

• Global constants: DefinePlugin (build-time feature flags).

• Cleaning and copying: output.clean, copy plugins for static assets.

• Analysis: bundle analyzer plugins generate treemaps and stats reports.

A practical heuristic:

• If you find yourself asking “how do I transform this file type?”, you want a loader.

• If you’re asking “how do I change chunking, output, caching, or inject build artifacts?”, you want a plugin.

Bundle size and performance: code splitting, tree shaking, caching, and runtime strategy

Optimizing a bundle is not about chasing a tiny number. It’s about fast startup, predictable caching, and stable long-term maintainability.

Measure first: build budgets and visibility

Before tuning, make bundle size visible:

• Generate stats.json and keep it as an artifact in CI for regressions.

• Use a bundle analyzer to spot “accidental megabytes” (moment locales, duplicated libraries, polyfills).

• Define a performance budget: max initial JS, max CSS, and max critical chunks.

Even small improvements compound when you ship frequently.

Code splitting: split by user journeys, not by file types

Webpack code splitting is driven by import().

// route-level split

const SettingsPage = lazy(() => import("./pages/settings"));

This is the most maintainable strategy because it aligns with how users navigate.

The splitChunks baseline

Webpack's optimization.splitChunks can reduce duplication and improve caching.

optimization: {

splitChunks: {

chunks: "all",

cacheGroups: {

vendors: {

test: /[\\/]node_modules[\\/]/,

name: "vendors",

chunks: "all",

},

},

},

}

Avoid over-engineering cache groups. If you create 20 micro-vendor chunks, you can increase request overhead and make debugging harder.

A pragmatic target:

• 1 “vendors” chunk for broadly used deps

• route chunks for pages

• feature chunks when a feature is heavy and optional

Tree shaking: make it work reliably

Tree shaking is a compiler optimization that removes unused exports. It depends on signals:

• ESM syntax (import / export)

• libraries that publish ESM builds

• sideEffects metadata

• minification (dead code elimination is more effective post-minify)

Checklist when “webpack tree shaking is not working”:

- Ensure your transpilation keeps ES modules (Babel

modules: false). - Use

mode: "production"or setoptimization.usedExports = true. - Mark safe packages/files as

"sideEffects": false(or a precise array) inpackage.json. - Prefer named imports from ESM-friendly libraries.

- Verify with a bundle analyzer and

stats.jsonexport usage.

Tree shaking is not a single switch. It’s a contract between your code, your dependencies, and your bundler.

Long-term caching: content hashes, stable module ids, runtime chunk

Caching success means users rarely re-download unchanged code.

Key ingredients:

• filename: [name].[contenthash] for chunks and assets

• stable module ids: optimization.moduleIds = "deterministic"

• stable chunk ids: optimization.chunkIds = "deterministic"

• extract the runtime: optimization.runtimeChunk = "single"

optimization: {

moduleIds: "deterministic",

chunkIds: "deterministic",

runtimeChunk: "single",

}

This reduces “cache churn”, especially when you add a new dependency.

Source maps: pick the right trade-off

Source maps help debugging but can slow builds and expose code.

Pragmatic choices:

• Dev: eval-cheap-module-source-map (fast rebuilds)

• Prod: source-map for high-trust internal apps, or hidden-source-map / nosources-source-map for safer external releases

Make it intentional. Align it with your security posture.

Module Federation: micro-frontends without the copy-paste tax

Module Federation (webpack 5) lets you load remote bundles at runtime and share dependencies. Done well, it enables micro-frontends with less duplication and faster independent deployments.

Done poorly, it creates a distributed monolith. Architecture matters.

The core idea: host, remotes, and shared dependencies

In Module Federation:

• A remote exposes modules (like a feature package).

• A host consumes those exposed modules dynamically.

• A shared section coordinates dependency versions and singletons.

This is not just build config. It’s a runtime integration contract.

Step-by-step: a minimal federation setup

Remote app: expose a public module

new ModuleFederationPlugin({

name: "profile",

filename: "remoteEntry.js",

exposes: {

"./ProfileWidget": "./src/widgets/profile",

},

shared: {

react: { singleton: true, requiredVersion: "^18.0.0" },

"react-dom": { singleton: true, requiredVersion: "^18.0.0" },

},

})

A strong pattern is to expose only public API modules, not internal file paths.

Host app: consume the remote module

new ModuleFederationPlugin({

name: "shell",

remotes: {

profile: "profile@https://cdn.example.com/profile/remoteEntry.js",

},

shared: {

react: { singleton: true, requiredVersion: "^18.0.0" },

"react-dom": { singleton: true, requiredVersion: "^18.0.0" },

},

})

In code:

// dynamic import from remote

const ProfileWidget = lazy(() => import("profile/ProfileWidget"));

Add fallbacks:

• skeleton UIs

• retry on transient network failures

• graceful degradation if a remote is unavailable

Versioning and shared dependency pitfalls

Federation pain often comes from mismatched versions and implicit coupling.

Mitigation checklist:

• Share only what must be shared (React often must be singleton).

• Use requiredVersion to avoid silent incompatibilities.

• Define a compatibility policy (e.g., “remotes support React 18 minor updates”).

• Avoid sharing stateful libraries unless you truly need a singleton.

A healthy micro-frontend system treats each remote as a product boundary, not just a repo boundary.

Why Module Federation pairs well with Feature-Sliced Design

Feature-Sliced Design encourages clear boundaries:

• Slices expose a controlled public API

• Dependencies flow from higher-level layers to lower-level ones

• Shared code becomes explicit in shared/, not accidental imports

A practical mapping for micro-frontends:

• A remote app can own a set of pages/, widgets/, and features/

• The host owns the app/ shell and global routing composition

• shared/ is shared by convention, not by default imports across teams

This reduces the risk of “remote internals” leaking into the host.

Debugging webpack build issues: a practical checklist

Webpack debugging feels hard when you treat errors as mysteries. It becomes straightforward when you treat them as graph and resolution problems.

1) “Module not found” and resolution failures

Most resolution issues come from:

• missing file extensions in resolve.extensions

• incorrect resolve.alias

• TypeScript path aliases not mirrored in webpack

• monorepo symlinks and resolve.symlinks behavior

Checklist:

- Confirm the exact import path in the error.

- Check

resolve.extensionsincludes your file types. - Mirror TS aliases in webpack (or generate them from a single source).

- In monorepos, verify symlink handling and workspace node_modules layout.

2) Loader errors: “You may need an appropriate loader”

This usually means the file matched no rule.

Fix pattern:

- Identify the file extension and loader chain you expect.

- Confirm

testregex matches the path (watch for.mjs,.cjs,.module.css). - Ensure the loader is installed and referenced correctly.

- If using

oneOf, make sure the intended rule is reachable.

A quick sanity check is to log rules and verify order. Loader rules are applied in a deterministic, but sometimes surprising, way.

3) CSS order conflicts and “chunk style” warnings

Common causes:

• mixing CSS extraction with style injection inconsistently

• importing global CSS from deep inside features, causing non-obvious ordering

• multiple entry points with shared CSS

Mitigations:

• Keep global styles in a predictable place (e.g., app/styles).

• Prefer CSS Modules for local styles.

• Extract in prod consistently and avoid mixing modes.

4) Tree shaking and duplicate dependencies

If a dependency shows up twice:

• You may have multiple versions installed (lockfile drift).

• Federation remotes may not share a singleton dependency.

• You may import both ESM and CJS builds.

Tools that help:

• Inspect stats.json for module duplication.

• Check npm ls <package> / pnpm why <package>.

• Align versions and enforce them via workspace constraints.

5) Slow builds and rebuilds

Webpack performance tuning is often about reducing work:

• enable persistent caching: cache: { type: "filesystem" }

• reduce expensive source maps in dev

• avoid transpiling node_modules unless necessary

• use thread loaders selectively (they can backfire on smaller projects)

Profiling strategy:

- Run a build with profiling and generate stats.

- Identify the slowest loaders and largest modules.

- Optimize the hot spots first (often TS/JS and CSS tooling).

6) Debugging the build like a system

When issues are persistent:

• enable more logging: infrastructureLogging

• inspect emitted chunk names and module ids

• validate that dynamic imports create the chunks you intend

• treat the build as a reproducible pipeline in CI

The strongest teams keep build diagnostics as a first-class artifact, not a last resort.

When webpack feels “too complex”, the real issue is architecture

Webpack configuration complexity is often a symptom of unclear boundaries in the codebase.

If everything can import everything, then:

• chunking becomes unpredictable

• tree shaking becomes less effective

• refactoring breaks hidden dependencies

• Module Federation becomes risky because “public APIs” are undefined

In other words, bundling and architecture are the same conversation.

How different architectural approaches scale

| Approach | What it optimizes | Scaling pain points |

|---|---|---|

| MVC / MVP | Simple separation of concerns for UI and logic | Cross-feature coupling grows; boundaries blur in large apps |

| Atomic Design | Consistent UI composition (atoms → organisms) | Great for design systems; weaker guidance for business logic boundaries |

| Feature-Sliced Design (FSD) | Modular, feature-oriented boundaries with controlled public APIs | Requires discipline and boundary enforcement; needs shared conventions |

Domain-Driven Design (DDD) also adds valuable language around bounded contexts and explicit domain modeling. FSD complements that by giving frontend teams a practical folder and dependency model that scales with product complexity.

The FSD core: layers, slices, and public API

Feature-Sliced Design organizes code by responsibility and dependency direction.

Common layers (from higher-level orchestration to lower-level primitives):

• app/ – app initialization, providers, global styles, routing

• pages/ – route-level composition

• widgets/ – reusable UI blocks composed from features/entities

• features/ – user-facing interactions and business capabilities

• entities/ – domain entities and their logic/UI representations

• shared/ – reusable UI kit, libs, configs, API clients, primitives

Within layers, slices group cohesive code. A slice has:

• clear ownership

• internal modules hidden by default

• a public API (for example, index.ts) that other slices import from

This increases cohesion and reduces coupling—two properties that make both architecture and webpack chunking simpler.

A concrete FSD-friendly directory sketch

src/

app/

providers/

routing/

styles/

index.tsx

pages/

settings/

ui/

index.ts

profile/

ui/

index.ts

widgets/

header/

ui/

index.ts

sidebar/

ui/

index.ts

features/

auth-by-password/

model/

ui/

api/

index.ts

update-profile/

model/

ui/

index.ts

entities/

user/

model/

ui/

api/

index.ts

session/

model/

index.ts

shared/

ui/

lib/

api/

config/

assets/

Notice how this structure naturally supports:

• predictable route-level code splitting (pages/*)

• meaningful chunk naming (by slice)

• controlled imports (public API)

• safer federation exposes (export only the slice public API)

As demonstrated by projects using FSD, teams can onboard faster because the structure tells a story: “where should this code live, and who is allowed to import it?”

Putting it together: an FSD-friendly webpack setup for real teams

The goal is not a fancy config. The goal is a build system that stays stable as the product evolves.

1) Align webpack aliases with architectural boundaries

Path aliases reduce import noise and make boundaries visible.

resolve: {

alias: {

"@app": path.resolve(__dirname, "src/app"),

"@pages": path.resolve(__dirname, "src/pages"),

"@widgets": path.resolve(__dirname, "src/widgets"),

"@features": path.resolve(__dirname, "src/features"),

"@entities": path.resolve(__dirname, "src/entities"),

"@shared": path.resolve(__dirname, "src/shared"),

},

extensions: [".ts", ".tsx", ".js", ".jsx", ".json"],

}

Then enforce boundaries with tooling:

• ESLint rules for restricted imports

• dependency-cruiser style checks in CI

• conventions: import from slice public API only

This turns “architecture” into something the build and CI can validate.

2) Make code splitting match the FSD composition model

A simple, effective policy:

• pages/ are route-level chunks

• heavy features/ are lazy-loaded behind user intent

• shared/ stays small and stable to maximize cache hit rates

Example:

// load a feature only when needed

const ExportReport = lazy(() => import("@features/export-report"));

This tends to produce:

• smaller initial JS

• fewer accidental cross-feature dependencies

• more stable chunk graphs

3) Apply splitChunks with architecture-aware naming

You can keep splitChunks mostly default, but add a little structure:

• a vendors chunk

• a runtime chunk

• allow route and feature chunks to remain meaningful

If you overfit cache groups to folder names, you risk brittle configs. Prefer stable, minimal rules.

4) Prepare for Module Federation with public APIs

If you plan to adopt micro-frontends, FSD gives you a natural federation surface:

• expose pages/* or widgets/* via their index.ts

• avoid exposing deep internal paths

• treat each remote as a bounded capability

Remote exposure example (conceptually):

• Good: ./ProfilePage: ./src/pages/profile

• Risky: ./UserStore: ./src/entities/user/model/store (leaks internal contracts)

Public APIs make federation safer, testing easier, and refactoring less risky.

5) A pragmatic workflow for migrating an existing codebase

If you’re “taming webpack” in a legacy frontend, do not rewrite everything. Make progress with controlled steps:

- Stabilize build outputs: content hashes, deterministic ids, baseline splitChunks.

- Identify boundaries: list top-level user flows and domain entities.

- Create

shared/andentities/first: move primitives and stable domain logic. - Move one feature at a time into

features/, add a public API, and update imports. - Introduce pages/widgets composition to reflect the UI structure.

- Enforce boundaries in CI to prevent regressions.

This approach reduces risk while producing visible wins: clearer ownership, smaller diffs, and better bundling outcomes.

Conclusion

Webpack becomes approachable when you treat it as a system: a module graph transformed into a chunk graph, shaped by intentional loaders, plugins, and optimization. A clean webpack.config.js baseline, a clear understanding of loaders vs plugins, and disciplined bundle strategies like code splitting, tree shaking, and long-term caching will keep your builds fast and predictable. If you add Module Federation, make it a contract—hosts and remotes should share only what they must, and expose only stable public APIs. Over time, adopting a structured architecture like Feature-Sliced Design is a long-term investment in code quality, refactoring speed, and team productivity.

Ready to build scalable and maintainable frontend projects? Dive into the official Feature-Sliced Design Documentation to get started.

Have questions or want to share your experience? Visit our homepage to learn more!

Disclaimer: The architectural patterns discussed in this article are based on the Feature-Sliced Design methodology. For detailed implementation guides and the latest updates, please refer to the official documentation.