The Architect's Guide to Maintainable Frontend

TLDR:

Large frontend apps fail slowly—through rising coupling, unclear boundaries, and compounding technical debt. This architect’s guide explains what makes code maintainable, how to measure it with practical signals (complexity, churn, dependency health), and which architectural patterns scale. You’ll see how Feature-Sliced Design (FSD) enforces modularity with layers, slices, and public APIs—making frontend refactoring safer and faster.

Code maintainability is what separates a frontend that scales confidently from one that collapses under technical debt, software entropy, and risky frontend refactoring. As SPAs expand, the real challenge becomes controlling coupling, preserving modularity, and keeping change safe. Feature-Sliced Design (FSD) on feature-sliced.design offers a modern, enforceable methodology to structure UI, business logic, and dependencies so teams can deliver faster with less friction.

Why Code Maintainability Is the Frontend Architect’s Primary KPI

A key principle in software engineering is that the ability to change the system safely is more valuable than any single implementation detail. In frontend work, change arrives constantly: new product flows, redesigned UI, altered backend contracts, shifting performance budgets, new compliance rules, and framework upgrades. When code maintainability is high, these changes feel routine. When it’s low, every ticket becomes a negotiation with fragile state, unclear ownership, and unintended side effects.

Maintainability matters even more in the frontend because the UI is where domain complexity meets interaction complexity:

• Business logic lives in the UI now. Eligibility rules, pricing variants, role-based access, onboarding funnels, and experiment flags frequently land in the client.

• State is distributed. Router state, server cache, local state, form state, and global state can drift into inconsistent “truths.”

• Dependencies churn. Build tools, component libraries, and frameworks evolve quickly, and upgrades can expose architectural weaknesses.

• Teams scale. More developers means more parallel work, and without consistent structure you get merge conflicts, duplication, and divergent patterns.

When you design for code maintainability, you get compounding benefits:

- Reduced cognitive load: developers reason locally instead of scanning the whole repo.

- Safer change: bounded modules and explicit contracts make refactors predictable.

- Faster onboarding: consistent project structure shortens the “time to first meaningful PR.”

- Lower defect rate: isolated changes reduce regression risk.

- Sustained delivery velocity: fewer “slowdown months” caused by architecture drift.

Leading architects suggest treating maintainability as a productivity multiplier: the same team can ship more value with fewer late surprises when the system is structured for change.

What “Maintainable Frontend Code” Actually Means

“Maintainable” isn’t a vague compliment. It’s a set of technical properties that make a codebase easy to understand, safe to modify, and resilient to growth. In practice, code maintainability comes from aligning architecture with how the product changes.

Coupling and cohesion: the foundation of maintainability

Low coupling means modules interact through small, stable interfaces. High cohesion means code that changes together lives together. In a frontend, poor cohesion often shows up as business logic scattered across hooks/, utils/, services/, and UI folders—making even small changes expensive.

Signals of strong cohesion and low coupling:

• A feature can be modified without touching unrelated files.

• Dependencies follow clear direction (no “imports that go everywhere”).

• Modules can be deleted or replaced with minimal fallout.

• The “public surface” of a module is small and intentional.

Boundaries you can enforce, not just describe

A maintainable architecture needs boundaries that are enforceable:

• Public API: other modules import only from an approved entry point (for example, an index.ts).

• Dependency direction: a consistent rule prevents circular dependencies and backdoor imports.

• Isolation of side effects: network calls, storage, and analytics are behind adapters instead of leaking into UI components.

Without enforceable boundaries, architecture becomes a suggestion—and software entropy slowly wins.

Local reasoning and explicit contracts

A rare but powerful maintainability attribute is local reasoning: the ability to understand a module by reading only that module and its public dependencies. You get local reasoning when:

• inputs/outputs are explicit (types, interfaces, function signatures)

• side effects are isolated

• state transitions are predictable

• imports reflect real dependencies, not convenience

This is where code maintainability becomes felt: code review improves, debugging becomes calmer, and refactoring becomes routine.

Measuring Code Maintainability in Real Projects

Measuring code maintainability is not about chasing one magic score. It’s about tracking actionable signals that correlate with risk, complexity, and change cost. The best approach combines:

• Static metrics (structure today)

• Evolutionary metrics (how code changes over time)

• Architectural fitness functions (automated checks that prevent drift)

Static maintainability signals that actually help

Static analysis is useful when it answers: “Where should we invest to make future change easier?” The most reliable signals relate to complexity, duplication, and dependency health.

| Signal (Static) | Why it predicts maintainability | Practical action |

|---|---|---|

| Cognitive/cyclomatic complexity | Complex functions are harder to reason about and refactor safely | Split logic into smaller pure helpers; improve naming and types |

| Duplication and clones | Duplicated logic multiplies bug fixes and creates divergence | Extract shared intent (domain or feature), not generic "utils" |

| Dependency cycles | Cycles create hidden contracts and fragile refactoring | Break cycles with adapters; enforce no-cycles in CI |

| Deep imports | Importing internals couples modules to implementation details | Introduce slice-level public APIs and ban deep imports |

| Type coverage / strictness | Strong types reduce ambiguity and make refactors safer | Increase strictness where domain logic is volatile or high-impact |

A lightweight dashboard can keep maintainability visible without turning it into a vanity metric:

| Area | Target | Example threshold |

|---|---|---|

| Dependency integrity | No new cycles | Build fails on cycle detection |

| Complexity hotspots | Fewer high-risk functions | Cognitive complexity > 15 triggers review |

| Boundary discipline | Public API-only imports | No ../internal/* imports allowed |

This kind of dashboard helps teams have positive, concrete conversations about code maintainability: “Which hotspot is worth addressing this sprint?” rather than “Our architecture feels messy.”

Evolutionary metrics: churn, hotspots, and change amplification

Static metrics show you what’s complicated. Evolutionary metrics show you what’s expensive over time.

• Churn: files that change frequently are a good place to improve boundaries and test coverage.

• Hotspots: combine churn with complexity to find modules that are both volatile and difficult.

• Change amplification: if a small change touches many folders, boundaries are leaking.

• Bug correlation: repeated regressions in the same area often indicate missing isolation or unclear contracts.

A maintainability-friendly workflow is a monthly “hotspot review”:

- Identify top 5 hotspots (churn × complexity).

- Pick one hotspot with high business impact.

- Improve it with a bounded refactor (public API, better module boundaries, tests).

- Track whether future changes become smaller and safer.

Architectural fitness functions: maintainability that enforces itself

For large teams, maintainability must be automated. Fitness functions in CI can protect code maintainability from slow erosion:

• no dependency cycles

• layer import direction rules

• public API-only imports

• banned cross-slice internal imports

• bundle size or route-level performance budgets

The benefit is consistent: architectural integrity no longer depends on a few senior developers remembering the rules.

Common Frontend Architectures and Their Maintainability Trade-offs

Most teams adopt patterns in layers: component libraries, state management, and folder conventions. The maintainability challenge is that many approaches optimize one dimension (UI reuse, technical separation, team autonomy) while leaving boundaries ambiguous.

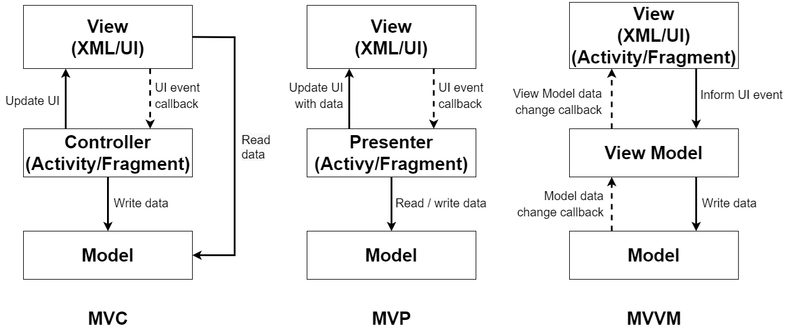

Layered patterns (MVC, MVP, MVVM): clear roles, limited scalability

Layered architectures split by technical responsibility:

• MVC: Model, View, Controller

• MVP: Model, View, Presenter

• MVVM: Model, View, ViewModel

These are excellent for clarity in small-to-medium systems, especially when presentation logic stays manageable. The maintainability risk appears when “controllers” or “view-models” become dumping grounds for every edge case, turning into “god modules” with massive coupling.

Maintainability win: easy to learn, simple separation of concerns.

Maintainability risk: fat controllers/view-models, unclear feature ownership.

Component-first organization and Atomic Design: great UI reuse, weaker domain boundaries

Component-based architecture (React, Vue, Angular) is foundational. Atomic Design (atoms → molecules → organisms → templates → pages) is especially strong for design systems and consistent UI.

The common failure mode is that Atomic Design doesn’t prescribe where business logic lives. Teams often end up with:

• components/ clean and reusable

• hooks/, services/, store/ becoming tangled and cross-cutting

Maintainability win: consistent UI and reusable components.

Maintainability risk: business logic scattered; cross-feature coupling in shared hooks.

Domain-Driven Design (DDD) thinking: strong alignment, needs governance

DDD brings powerful ideas to frontend architecture:

• bounded contexts

• ubiquitous language

• domain entities and use-cases

• clear ownership and “why the code exists”

This improves code maintainability when the business is complex (payments, subscriptions, workflows). The risk is over-modeling or inconsistent boundary enforcement.

Maintainability win: code matches business concepts; ownership becomes clearer.

Maintainability risk: boundaries drift without rules; shared domain internals leak across contexts.

Micro-frontends: autonomy at the cost of integration complexity

Micro-frontends can help large organizations ship independently. They can improve maintainability at the organizational level, but add complexity:

• runtime integration

• shared design system alignment

• cross-app routing and authentication

• duplicated platform concerns

• inconsistent observability and error handling

Maintainability win: independent deployments for multiple teams.

Maintainability risk: fragmented UX and duplicated infrastructure; higher operational overhead.

Comparative table: what each approach optimizes

| Approach | What it optimizes | Typical maintainability failure mode |

|---|---|---|

| MVC/MVP/MVVM | Technical separation and clarity | "Fat" logic layers and implicit contracts |

| Atomic Design | UI consistency and reuse | Business logic scattered outside clear boundaries |

| DDD-inspired modules | Domain alignment and ownership | Boundary erosion without enforcement |

| Micro-frontends | Team autonomy and independent delivery | Integration overhead and duplicated concerns |

| Feature-Sliced Design | Enforceable boundaries + feature cohesion | Partial adoption without rules or tooling |

This is why many teams gradually “reinvent” a feature-oriented structure. Feature-Sliced Design makes that structure explicit and maintainable by design.

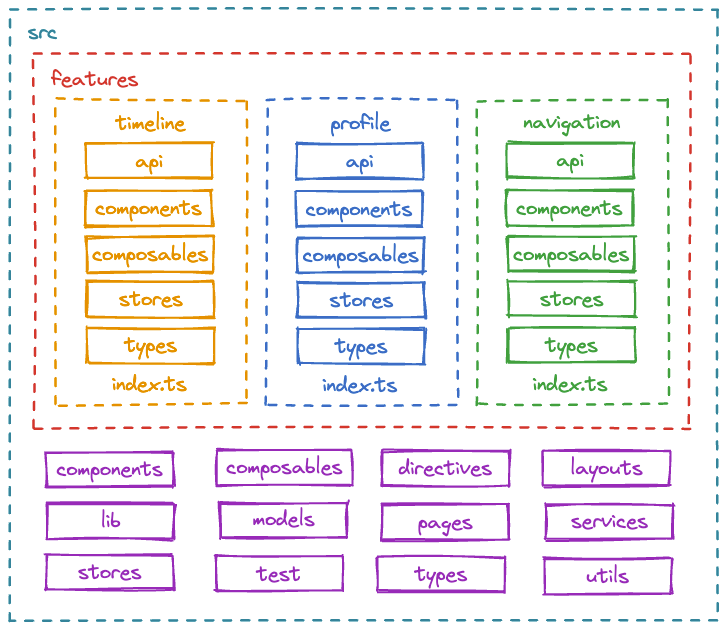

Feature-Sliced Design: A Maintainability-First Methodology

Feature-Sliced Design (FSD) is a robust methodology for structuring frontend projects to improve code maintainability through:

• layers (clear purpose and dependency direction)

• slices (cohesive modules around business value)

• public APIs (intentional import surfaces)

• unidirectional dependencies (no architectural backflow)

Based on experience with large-scale projects, this combination is especially effective at reducing technical debt and keeping frontend refactoring safe.

The layer model: a clear dependency rule

FSD typically uses these layers (names can vary, but intent is stable):

• shared: reusable, business-agnostic building blocks (UI kit, utilities, API client, config)

• entities: core domain concepts (User, Product, Order) and domain-level UI/state

• features: user scenarios (add-to-cart, sign-in, apply-filters) coordinating entities

• widgets: composite UI blocks combining features/entities (Header, Sidebar, CheckoutSummary)

• pages: route-level compositions

• app: initialization (providers, routing, global styles, app shell)

Dependency direction: higher layers may depend on lower layers, not the reverse.

app → pages → widgets → features → entities → shared

This rule directly supports code maintainability by preventing circular dependencies and hidden coupling. It keeps the architecture predictable: features don’t import pages, entities don’t depend on widgets, and shared code stays reusable.

Slices: building blocks of cohesion and ownership

A “slice” is a module organized around one concept: a feature scenario or an entity. This improves maintainability because it matches how teams think and how products change.

A typical project layout:

src/

app/

providers/

routing/

pages/

checkout-page/

product-page/

widgets/

header/

cart-summary/

features/

add-to-cart/

auth-by-email/

apply-filters/

entities/

user/

product/

cart/

shared/

ui/

api/

lib/

config/

Notice the navigational benefit: instead of hunting through hooks/ and services/, you go directly to the slice that owns the behavior. This reduces onboarding time and makes codebase maintainability visible in the file system.

Public API: enforce boundaries and make refactoring safer

FSD’s public API pattern turns “module boundaries” into real contracts. A slice exposes what others may use via an entry point (commonly index.ts). Other modules import only from the slice root.

Example:

// features/add-to-cart/index.ts (public API)

export { AddToCartButton } from "./ui/add-to-cart-button";

export { useAddToCart } from "./model/use-add-to-cart";

export type { AddToCartPayload } from "./model/types";

// widgets/cart-summary/ui.tsx

import { AddToCartButton } from "@/features/add-to-cart";

This boosts code maintainability in a very practical way:

• internal refactors don’t break external imports

• you can evolve implementation behind a stable contract

• accidental coupling through deep imports is reduced

• code review becomes simpler: “Is this part of the public API?”

Isolation of side effects: adapters over leakage

Frontends have side effects: HTTP, caching, analytics, storage, feature flags. Maintainability improves when those concerns are isolated behind adapters rather than sprinkled through UI.

A common pattern in FSD-compatible projects:

• shared/api holds transport logic (HTTP client, endpoints)

• entities/features map transport models to domain models

• features orchestrate workflows and UI interaction logic

• widgets/pages compose and configure, rather than own business logic

Flow:

shared/api → entities/* (domain mapping) → features/* (use-cases) → widgets/pages (composition)

This isolation reduces change amplification and keeps frontend code maintainability high as APIs evolve.

Best Practices That Improve Code Maintainability in Any Frontend

Architecture sets the map; day-to-day practices keep the map accurate. The following patterns align well with FSD and also improve maintainability in non-FSD codebases.

1) Design modules around “reasons to change”

Instead of organizing solely by file type (components, hooks, services), organize by business capability and user journey:

• “apply filters”

• “invite teammate”

• “confirm payment”

• “upload avatar”

• “reset password”

This reduces scattering and makes code maintainability visible: when a scenario changes, most of the work stays inside its slice.

2) Keep UI components composable and predictable

A maintainable component is easier to reuse and easier to test.

• Prefer props and events over hidden global access.

• Keep side effects in orchestration layers (features/widgets).

• Use controlled components for complex forms when it improves clarity.

• Make accessibility a default (keyboard, focus management, ARIA patterns).

This improves software maintainability because UI changes don’t require rewiring hidden dependencies.

3) Make state management boring (and explicit)

Most maintainability problems aren’t caused by the choice of state library—they’re caused by unclear ownership and ambiguous “source of truth.”

A healthy approach:

• Keep server-state in a dedicated cache layer (query client, request adapters).

• Keep UI-state close to UI when it’s local.

• Keep domain-state in entities when it’s shared and meaningful.

• Avoid “global store as a dumping ground.”

Explicit ownership reduces coupling and strengthens code maintainability.

4) Prefer domain-specific reuse over generic utilities

DRY is valuable, but “utility hell” is a maintainability trap. A better rule is: reuse intent, not implementation.

Instead of shared/lib/format.ts growing endlessly, you often want:

• entities/money for currency formatting and rounding rules

• entities/date for business-specific date logic

• features/discounts for pricing scenarios

This keeps cohesion high and avoids accidental coupling—two pillars of code maintainability.

5) TypeScript as a refactoring tool, not just type safety

Strong typing supports maintainability by making contracts explicit.

Pragmatic practices:

• Use strict mode where domain logic is critical.

• Prefer small, meaningful types and discriminated unions for UI states.

• Validate boundary inputs (API responses) before they enter core logic.

• Keep types close to the slice that owns them.

Types become living documentation, improving readability and code maintainability.

6) Test contracts at the slice boundary

Tests improve maintainability when they’re resilient to refactoring. Focus on contracts:

• unit tests for pure logic and mappers

• integration tests for feature flows through public APIs

• E2E tests for critical user journeys

Testing public behavior rather than internal structure reduces churn and supports frontend refactoring without fear.

7) Use “architecture-aware” linting and reviews

Maintainability is protected when rules are automatic:

• no deep imports across slices

• no forbidden dependency direction

• no new cycles

• consistent aliasing (@/features/* etc.)

This keeps architectural drift low and makes code maintainability the default outcome.

Technical Debt Management: Reduce Entropy Without Slowing Delivery

Technical debt becomes dangerous when it is invisible, unprioritized, and allowed to compound. A maintainable frontend treats debt as a managed engineering reality.

Classify debt by “interest rate”

Not all debt is equal. A practical approach is to rank debt by how expensive it makes future change:

• High-interest debt: hotspots that change often and break often (high churn + high complexity).

• Medium-interest debt: stable areas that are hard to understand but rarely changed.

• Low-interest debt: legacy corners scheduled for retirement or rarely touched.

This framing keeps conversations positive and aligned with outcomes: better code maintainability, safer releases, and faster delivery.

Create a lightweight debt register

A debt register can be a simple issue template:

- Location: slice/module and affected workflows

- Symptom: coupling, duplication, missing tests, unclear ownership

- Impact: slower delivery, regressions, onboarding pain, release risk

- Next step: one concrete refactor that fits a sprint

This makes technical debt actionable and keeps code maintainability improving steadily.

Prefer incremental refactoring over big rewrites

Big rewrites often create parallel complexity and delayed value. Incremental refactoring is more maintainable:

• pick one hotspot

• create or strengthen boundaries (public API, slice structure)

• add contract tests

• ship in small steps

FSD is particularly helpful here because slices and layers create natural refactoring units—making frontend refactoring predictable and low-risk.

Frontend Refactoring Playbook: Migrating Toward FSD Incrementally

You don't need a greenfield project to benefit from Feature-Sliced Design. You can adopt the methodology in phases and improve code maintainability without stopping feature work.

Phase 1: Stabilize the shared foundation

Create a coherent shared/ layer:

• shared/ui for consistent primitives

• shared/api for HTTP client and endpoint wrappers

• shared/lib for small, stable helpers

• shared/config for environment and feature flags

This reduces duplication and creates a reliable base for future modularization.

Phase 2: Introduce entities for core domain concepts

Identify stable business concepts (User, Product, Cart, Subscription) and create entity slices:

• domain types and validation

• domain UI components (cards, summaries)

• domain adapters/mappers

This centralizes meaning and reduces inconsistency—an immediate boost to code maintainability.

Phase 3: Extract one high-churn workflow into a feature slice

Pick a hotspot scenario, such as “add to cart” or “apply filters.” Move logic behind a feature public API.

Before/after:

Before:

components/ProductCard.tsx (calls API, updates store, tracks analytics)

hooks/useCart.ts

services/cartService.ts

After (directional and cohesive):

features/add-to-cart/

ui/

model/

index.ts

shared/api/cart.ts

entities/cart/

The improvement is tangible: fewer cross-cutting edits, clearer ownership, safer refactors.

Phase 4: Compose with widgets and pages

Create widgets for repeated composite blocks (Header, Sidebar, CheckoutSummary). Keep pages focused on composition and route wiring.

This reduces duplication and keeps orchestration where it belongs—supporting long-term code maintainability.

Phase 5: Enforce the architecture

Migration becomes durable when rules are enforced:

• layer import direction checks

• public API-only import rules

• no dependency cycles

• slice boundary rules

Once enforcement is in place, maintainability stops being an aspiration and becomes a property of the system.

Operating the Architecture: Keep Maintainability Stable as Teams Grow

A maintainable architecture thrives with lightweight governance that supports autonomy.

Define “done” with maintainability in mind

A practical definition of done can include:

• public API updated when contracts change

• no new boundary violations introduced

• tests added at slice boundaries for new workflows

• naming aligns with domain language and ownership

This keeps code maintainability consistent across teams and time.

Use ADRs to prevent architectural drift

Short Architecture Decision Records capture choices that affect maintainability:

• state management strategy

• API boundary and validation approach

• feature flag policy

• routing and page composition conventions

• shared UI ownership and versioning

ADRs reduce repeated debates and speed up onboarding—two direct benefits of strong code maintainability.

Review boundaries, not just style

High-leverage code review questions:

• Does this import bypass a public API?

• Does this change increase change amplification across slices?

• Is the domain logic placed in the correct layer?

• Are side effects isolated behind adapters?

• Will future refactoring be simpler after this PR?

This keeps the system clean while maintaining a positive, collaborative engineering culture.

Conclusion

Maintainable frontend systems are built through deliberate choices: low coupling, high cohesion, explicit boundaries, and dependable dependency direction. Measure code maintainability with practical signals like complexity hotspots, churn, and dependency health, then act on what you learn with incremental refactoring. Treat technical debt as a managed reality—visible, prioritized by interest rate, and reduced continuously. Most importantly, adopt an architecture that can enforce these principles at scale, not just describe them.

A structured methodology like Feature-Sliced Design is a long-term investment in code quality and team productivity. It helps teams mitigate software entropy, reduce refactoring risk, and keep large frontends navigable as the product grows.

Ready to build scalable and maintainable frontend projects? Dive into the official Feature-Sliced Design Documentation to get started.

Have questions or want to share your experience? Visit our homepage to learn more!

Disclaimer: The architectural patterns discussed in this article are based on the Feature-Sliced Design methodology. For detailed implementation guides and the latest updates, please refer to the official documentation.