The Ultimate Guide to Frontend State Architecture

TLDR:

This in-depth guide explores how to build a scalable and maintainable frontend state architecture using React state, Vue state, modern state management libraries (Redux, Zustand, MobX, Pinia), state patterns, and Feature-Sliced Design, helping teams avoid technical debt and scale confidently in production.

Primary keyword: state management

Secondary keywords: react state, vue state, frontend state

Audience: Mid-level to Senior Frontend Developers, Tech Leads, Architects

Goal: choose the right patterns and structure for scalable, maintainable application state (not just a new library)

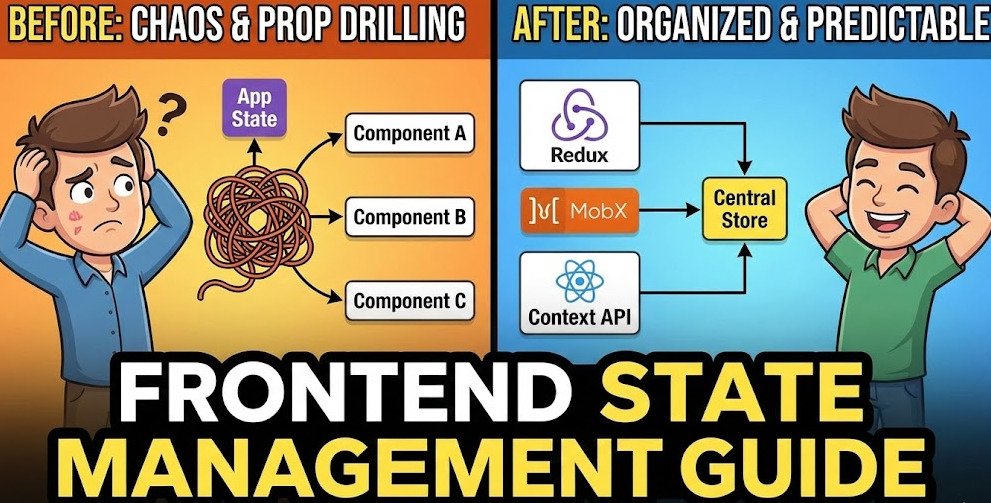

State management is where otherwise clean frontends turn into a tangle of global state, inconsistent React state updates, and hard-to-reason-about frontend architecture. Feature-Sliced Design (FSD) on feature-sliced.design provides a modern way to align state with business capabilities, enforce boundaries, and keep a scalable state management strategy. This guide breaks down patterns, libraries, and an architecture-first approach you can apply to React, Vue, and beyond.

Table of contents

• Why state management gets hard

• A taxonomy of frontend state

• Common approaches and trade-offs

• Choosing a library (Redux, Zustand, MobX, Pinia)

• Architecture principles

• Methodologies compared

• FSD as a state architecture

• Emerging paradigms: atoms, signals, machines

• Step-by-step blueprint

Why state management gets hard in large frontend applications

A key principle in software engineering is that complexity grows faster than features unless you actively design boundaries. State is the sharp end of that complexity because it crosses time (async), space (components), and teams (ownership).

Here are the forces that make frontend state and state orchestration hard at scale:

• State-space explosion: If you model UI with many independent flags, your possible states grow exponentially. With n boolean flags, the system has 2ⁿ combinations. Ten “simple” flags already implies 2¹⁰ = 1024 possible UI configurations—before you add loading, errors, permissions, and retries.

• Mixed concerns in one store: UI state (modals, filters), domain state (cart, auth), and server state (cache, pagination) get shoved into one “app store”. Cohesion drops, coupling rises.

• Implicit dependencies: When any module can import any other module’s store, you get “action-at-a-distance”. A small change in one reducer/observable can break distant screens.

• Asynchrony and concurrency: Real apps include cancellation, race conditions, optimistic updates, background refetch, offline mode, and real-time streams.

• Multiple sources of truth: Routing state, URL params, form state, server cache, and local drafts can all represent “the current value”. Without a policy, bugs feel random.

If you’re fighting prop drilling, “god” contexts, ever-growing Redux slices, or Vuex/Pinia stores that know about UI details, the problem isn’t just choosing “the best state management library”. It’s state architecture.

A practical taxonomy of frontend state

Before you pick patterns or tools, classify what you’re managing. “State management” is really a portfolio of different state types with different failure modes.

UI state vs domain state vs server state

UI state (presentation state)

Examples: open/closed modal, active tab, drag state, client-side sorting, input drafts.

Healthy default: keep it local to the component or widget; derive from props when you can.

Domain state (business state)

Examples: cart items, selected plan, permissions, auth session, feature flags, workflow steps.

Healthy default: model it explicitly, give it a clear owner, and expose a stable public API.

Server state (remote/cache state)

Examples: product list, user profile, paginated search results, GraphQL cache.

Healthy default: use a dedicated server-state cache (queries) with invalidation and deduplication.

A useful mindset: treat these as different systems with different optimizations.

• UI state → locality and render performance

• Domain state → invariants, traceability, correctness

• Server state → caching, synchronization, freshness

Source of truth vs derived state

Source of truth is the minimal state you must store.

Derived state is computed from other state (selectors, computed, memoized values).

Storing derived state creates drift. Prefer:

• Redux selectors / memoization

• MobX computed values

• Vue computed refs

• derived atoms/selectors (atomic state)

• read-only view models

Rule of thumb: If you can recompute it deterministically, don’t store it.

Transient vs persistent state

• Transient (ephemeral) state: lives for one interaction (hover, typing).

• Persistent state: survives navigation/reload (session, settings), often stored in storage.

Be explicit about persistence. Persistent global stores that also hold transient UI toggles become brittle.

Common approaches to frontend state management and their trade-offs

Most teams climb a ladder of techniques. Each step solves one pain and introduces another.

Local component state

When it shines

• cohesive UI interactions

• fast iteration, minimal surface area

• great for useState/useReducer, Vue ref/reactive

Common pitfalls

• duplicated logic across components

• hard to share across siblings

• “shadow copies” of derived values

A robust methodology for large apps keeps local state local. Don’t centralize by default.

Lifting state up and prop drilling

Move state to the nearest common parent and pass props down (unidirectional data flow).

Pros

• explicit data flow

• easy to test as pure props

• no extra dependency

Cons

• “plumbing” overwhelms business logic

• fragile component APIs

• refactors become expensive

Prop drilling isn’t a failure; it’s feedback that your boundaries don’t match your state scope.

Context and dependency injection

React Context and Vue provide/inject are excellent for stable dependencies:

• theme, i18n, router, analytics, feature flags

• service instances, environment adapters, query clients

They are less ideal as a universal store:

• ownership becomes unclear

• “god context” emerges

• updates may trigger broad re-renders if not carefully segmented

A pragmatic rule:

• Context for configuration and infrastructure

• Stores for mutable domain state

External stores: centralized vs modular

At some scale, you need a state container:

• Redux Toolkit / NgRx (explicit events, predictable updates)

• MobX (reactive observables, computed derivations)

• Zustand / Pinia (lightweight modular stores)

• Atomic state (Jotai/Recoil-like)

• State machines (XState)

• RxJS streams (event-driven state)

The architectural question is: how do we keep coupling low and cohesion high as the app grows?

Pattern-level decision table

| Approach | Works best when… | Watch-outs |

|---|---|---|

| Local state + props | state belongs to one UI subtree | prop drilling, duplicated logic |

| Context-based shared state | shared config/dependency, rarely changing values | god contexts, unclear ownership |

| External store (feature-scoped) | multiple screens share domain behavior | cross-feature imports without boundaries |

| Server-state cache (queries) | data comes from backend and needs caching | mixing server state with domain/UI state |

| State machine / workflow | flows have explicit stages & transitions | upfront modeling effort |

Choosing a state management library: Redux vs Zustand vs MobX vs Pinia (and what they don’t replace)

Search intent often looks like “best state management library”. In practice, library selection should follow architecture decisions: What must be shared? Who owns it? How is it accessed via a public API?

Leading architects suggest evaluating these criteria:

• Predictability: can you reason about updates and invariants?

• Debuggability: devtools, logging, traceability, time-travel (where applicable)

• Scalability: can multiple teams work without stepping on each other?

• Performance: minimal re-renders, efficient derived state

• Testability: can you test state logic without UI?

• Integration: SSR, hydration, persistence, TypeScript types, tooling

Library comparison (pragmatic, architecture-aware)

| Library | Best fit | Typical trade-offs |

|---|---|---|

| Redux Toolkit | large teams, explicit actions/reducers, strong ecosystem, great TypeScript story | more ceremony than minimal stores; risk of mega-slices without boundaries |

| Zustand | small API, feature-level stores, easy composition | without architectural rules, “import-any-store” becomes de facto global state |

| MobX | highly reactive UIs, powerful computed state | implicit dependencies can hide coupling; data flow audits are harder |

| Pinia (Vue) | Vue-first store, Composition API ergonomics | still needs ownership design; avoid turning Pinia into a dumping ground |

What about Redux Toolkit Query, TanStack Query, SWR, Apollo?

These tools focus on server state management:

• caching and deduplication

• background refetch and invalidation

• optimistic updates

• request status and error handling

They complement domain stores rather than replacing them. Use query caches for remote data, and keep domain workflows (drafts, wizards, permissions, cross-step flows) in your domain layer.

A quick rule for React state vs Vue state

• If it’s UI-only and scoped: keep it local (useState, ref)

• If it’s remote/cache: prefer a query cache

• If it’s business behavior shared across screens: use a store, but scope it to a feature/entity/process

Architecture principles for scalable frontend state

A robust state architecture is less about where values live and more about how modules communicate.

Principle 1: Boundaries first, then state containers

State becomes spaghetti when any module can:

• import internal store details

• call actions directly across unrelated features

• read/write without constraints

Instead, define module boundaries and expose a public API:

• reads via selectors/queries

• writes via commands/actions

• events emitted for cross-module reactions

• types exported from one entry point

This reduces coupling and makes refactoring safe.

Principle 2: Separate reads from writes (and keep writes boring)

Writes should be easy to audit.

Practical tactics:

• name writes as business commands: applyCoupon, loginSucceeded, submitOrder

• keep update functions pure where possible

• keep side effects in a dedicated layer (effects, thunks, services)

• avoid “write anywhere” patterns

Even with MobX or signals, you can centralize mutations into explicit methods.

Principle 3: Model invariants close to the data

A common failure mode is scattering business rules across UI handlers.

Prefer domain-centric state:

• normalization (IDs + dictionaries) for large collections

• invariants enforced in reducers/actions/methods

• derived selectors for views

Example of normalized state:

cart = {

itemsById: { "p1": { id: "p1", qty: 2, price: 10 } },

itemIds: ["p1"],

coupon: "WELCOME"

// totals are derived, not stored

}

Principle 4: Make async and error states explicit

Async is where bugs hide: stale data, race conditions, and confusing spinners.

Track async explicitly:

• request status: idle | loading | success | error

• typed error payload and ownership

• cancellation and retry policy

• optimistic update policy

• invalidation strategy for cached data

Principle 5: Compose multiple focused stores instead of one mega-store

A scalable approach usually looks like:

• feature stores for user actions

• entity stores for reusable business entities

• process/workflow state for multi-step flows

• app-level state for true globals (rare)

This matches team ownership and keeps app state understandable.

How architectural methodologies influence state: MVC, MVP, Atomic Design, DDD, and FSD

Different methodologies shape where state ends up and how it’s accessed.

| Methodology | What it optimizes | State-related friction at scale |

|---|---|---|

| MVC / MVP | clear UI layering (Model/View/Controller or Presenter) | often unclear module boundaries; state leaks across screens |

| Atomic Design | UI composition and design systems | strong for UI structure, weaker guidance for domain/feature state ownership |

| Domain-Driven Design (DDD) | domain boundaries, aggregates, invariants | excellent for domain state, but needs frontend-friendly module layout and integration |

| Feature-Sliced Design (FSD) | modularity around features and business value | requires discipline in public APIs, but supports predictable growth |

Notice the gap: UI-focused methodologies rarely answer “where does checkout state live, who owns it, and how do pages interact safely?” That’s where FSD is especially practical.

Feature-Sliced Design as a state architecture

Feature-Sliced Design (FSD) is a methodology for frontend projects focused on modularity, explicit boundaries, and predictable growth. It doesn’t replace Redux, Zustand, MobX, or Pinia; it makes state management sustainable by telling you where state should live and how it should be exposed.

The core idea: align state with ownership

FSD organizes code by layers and slices, guided by dependency direction. Typical layers:

• app – app initialization, providers, global config

• processes – cross-page flows (checkout, onboarding)

• pages – route-level composition

• widgets – large UI blocks used on pages

• features – user actions with business meaning (add-to-cart, login)

• entities – business entities (user, product, cart)

• shared – reusable primitives (ui-kit, lib, api)

State lives where it belongs:

• UI-local state → pages / widgets UI

• Feature behavior state → features/<feature>/model

• Entity state and rules → entities/<entity>/model

• Workflow state → processes/<process>/model

• True global → app (keep small)

Public API is non-negotiable

Each slice exposes a public API (usually an index.ts), and other modules import only from it.

Typical slice structure:

features/

add-to-cart/

index.ts

model/

store.ts

selectors.ts

events.ts

ui/

AddToCartButton.tsx

lib/

mapProductToCartItem.ts

Public API example:

// features/add-to-cart/index.ts

export { AddToCartButton } from "./ui/AddToCartButton"

export { useAddToCart } from "./model/store"

export type { AddToCartError } from "./model/events"

This prevents accidental dependency cycles and makes state ownership obvious.

Example: React + FSD + Zustand (feature and entity boundaries)

entities/

cart/

index.ts

model/

store.ts

selectors.ts

lib/

totals.ts

features/

add-to-cart/

index.ts

model/

useAddToCart.ts

Entity store owns invariants:

// entities/cart/model/store.ts

createStore(() => ({

itemsById: {},

itemIds: [],

addItem: (item) => { /* enforce invariants */ },

removeItem: (id) => { /* ... */ }

}))

Feature orchestrates the user action:

// features/add-to-cart/model/useAddToCart.ts

const useAddToCart = () => {

const addItem = cartStore(state => state.addItem)

return (product) => addItem(mapProductToCartItem(product))

}

Result: cohesive stores, explicit public APIs, and fewer cross-cutting dependencies.

Example: Vue + FSD + Pinia (clean separation of concerns)

entities/

user/

index.ts

model/

user.store.ts

selectors.ts

features/

login/

index.ts

model/

login.store.ts

ui/

LoginForm.vue

Entity store holds user domain truth:

// entities/user/model/user.store.ts

defineStore("user", {

state: () => ({ session: null, roles: [] }),

getters: { isAuthenticated: (s) => !!s.session },

actions: { setSession(session) { /* ... */ } }

})

Feature store handles async lifecycle and errors:

// features/login/model/login.store.ts

defineStore("login", {

state: () => ({ status: "idle", error: null }),

actions: {

async submit(credentials) {

this.status = "loading"

try { /* call api, update user entity */ }

catch (e) { this.error = e; this.status = "error" }

}

}

})

This keeps vue state predictable and makes it easy to evolve authentication without rewriting pages.

Where server state belongs in FSD

Treat server-state tooling as infrastructure:

• shared/api – API client + base configuration

• entities/<entity>/api – endpoints, query keys, DTO mapping

• features/<feature> – orchestrate mutations and optimistic updates

• pages/widgets – consume queries and render

This reduces “query key soup” and keeps caching policies consistent.

Common FSD anti-patterns (and how to avoid them)

• Business stores in shared: increases fan-in and coupling. Keep shared for primitives.

• Cross-feature internal imports: enforce public APIs; use processes for orchestration.

• Pages owning business rules: pages compose; invariants live in entities, actions live in features.

As demonstrated by projects using FSD, these constraints improve onboarding and refactoring speed because intent is visible in the folder structure.

New paradigms: atomic state, signals, and state machines (how to use them without chaos)

Trends evolve, but architecture remains the stabilizer.

Atomic state management

Atomic approaches can reduce boilerplate and improve fine-grained updates. The risk: atoms become “global variables”.

Apply the same constraints:

• define atoms inside features or entities

• expose them only through public APIs

• group by domain, not by UI widgets

• avoid ad-hoc cross-slice imports

Signals and reactive primitives

Signals track dependencies precisely and can simplify derived state and performance. Still, signals don’t decide:

• ownership and boundaries

• where invariants live

• how cross-feature coordination works

• how to prevent dependency cycles

Signals are a mechanism; FSD is the organization.

State machines for workflows

For multi-step flows (checkout, onboarding), state machines provide clarity:

• explicit states and transitions

• fewer boolean flags

• better testability for edge cases

In FSD, workflow machines naturally belong in processes/<flow>/model.

Step-by-step: designing a frontend state architecture that scales

If you want a repeatable blueprint, use this sequence.

Step 1: Inventory and classify your state

List concerns and label them:

• UI / domain / server

• scope: leaf / subtree / cross-cutting

• persistence: transient / persistent

• ownership: which domain/team owns it?

This turns “state management is messy” into an actionable map.

Step 2: Define boundaries around business capabilities

Identify your primary slices:

• entities: user, product, cart, order

• features: login, add-to-cart, apply-coupon

• processes: checkout, onboarding

Then place state accordingly.

Step 3: Choose the smallest mechanism per class

• UI-only → local hooks/refs

• remote/cache → query cache

• domain behavior → feature/entity store

• complex flows → process store or state machine

This avoids “everything in Redux” or “everything in context”.

Step 4: Enforce public APIs and dependency direction

Practical enforcement:

• index.ts public APIs

• lint rules for restricted imports

• consistent segments: model, ui, api, lib

• code review checklist: “Is this import allowed?”

Step 5: Measure success with architecture-friendly signals

Useful leading indicators:

• fewer cross-slice imports of internals

• reduced prop drilling depth

• smaller, more cohesive stores

• more state logic covered by unit tests

• faster onboarding (less “where does this live?”)

Conclusion

State management becomes sustainable when you treat it as architecture: classify frontend state, scope it deliberately, and enforce boundaries so teams can evolve features without fear. The most reliable setups keep UI state local, use a server-state cache for remote data, and model domain behavior in focused stores with explicit writes, derived reads, and clear ownership. Feature-Sliced Design (FSD) reinforces these choices with dependency direction and public APIs, making refactoring cheaper and collaboration smoother as the codebase grows. Over time, this is a long-term investment in code quality, predictable delivery, and team productivity.

Ready to build scalable and maintainable frontend projects? Dive into the official Feature-Sliced Design Documentation to get started.

Have questions or want to share your experience? Visit our homepage to learn more!

Disclaimer: The architectural patterns discussed in this article are based on the Feature-Sliced Design methodology. For detailed implementation guides and the latest updates, please refer to the official documentation.