Clean Architecture in Frontend: A How-To Guide

TLDR:

Clean Architecture isn’t just a backend pattern. In frontend apps, it helps you separate business rules from UI, reduce coupling, and keep features maintainable as teams and requirements grow. This guide shows how to apply ports and adapters, structure layers in TypeScript, and integrate the approach naturally with Feature-Sliced Design for scalable, testable React or Angular codebases.

Clean architecture in frontend is the difference between a UI that evolves smoothly and a codebase that fights every change. When business rules live inside React components or Angular services, coupling grows, tests get brittle, and dependency inversion feels out of reach. Feature-Sliced Design (FSD) on feature-sliced.design provides a modern, frontend-native way to apply ports and adapters and keep modularity strong as the app scales.

Table of contents

• Why Clean Architecture matters in frontend

• The core ideas: dependency rule, layers, boundaries

• Mapping Clean Architecture to React and Angular

• How-to: implement Clean Architecture in a TypeScript frontend

• Dependency injection in frontend without pain

• Hexagonal, onion, ports-and-adapters: what differs, what doesn’t

• Comparing common frontend approaches: MVC, MVP, Atomic Design, DDD

• Where Feature-Sliced Design fits

• Migration playbook: from spaghetti UI to clean boundaries

• Is Clean Architecture worth it? A pragmatic decision framework

• Conclusion

Why Clean Architecture matters in frontend

A key principle in software engineering is: optimize for change, not for the current snapshot. Frontend systems change constantly—new products, redesigned flows, A/B experiments, regulatory updates, performance budgets, and new frameworks. The hard part is not shipping the first version; it’s shipping the 30th iteration without fear.

The most common failure mode: UI owns the business

Many teams start with “just components” and end up with:

• API calls inside components

• Validation rules duplicated across pages

• Feature flags sprinkled through UI branches

• “Smart” components that mutate state from everywhere

• Domain logic trapped in framework-specific abstractions (hooks, observables, stores)

This works—until it doesn’t. When you mix application logic with presentation, small changes trigger large refactors. Developers become hesitant to touch code, onboarding slows down, and architectural drift accelerates.

What Clean Architecture buys you (specifically in frontend)

Clean Architecture (and its close relatives—hexagonal architecture, onion architecture, and ports and adapters) is not about purity. It’s about managing dependencies so that:

• Business rules are testable without a browser, DOM, or framework runtime

• UI becomes replaceable (React → Solid, Angular → web components, etc.)

• Infrastructure (HTTP, storage, analytics, feature flags) is swapped behind interfaces

• Teams can work in parallel with clear boundaries and stable public APIs

• Refactoring becomes additive: you improve structure without stopping feature delivery

In practice, this translates into higher cohesion, lower coupling, clearer separation of concerns, and fewer “touch 20 files for a one-line change” moments.

The frontend twist: you can’t escape the framework, so isolate it

Unlike backend services, the frontend is always coupled to:

• A rendering model (React reconciliation, Angular change detection)

• A routing layer

• State management patterns

• Browser APIs and performance constraints

• Build tooling and module bundling

Clean Architecture doesn’t remove these constraints. It pushes them to the edges and keeps your core logic as framework-agnostic as is reasonable.

The core ideas: dependency rule, layers, boundaries

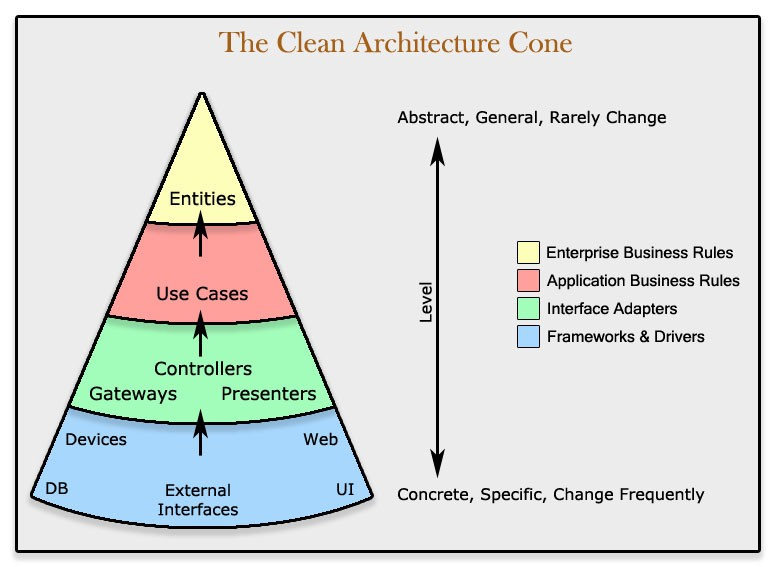

Clean Architecture is often explained with concentric circles. The memorable rule is the one that matters most:

The Dependency Rule: source code dependencies can only point inward (toward business rules). Outer layers depend on inner layers; inner layers do not depend on outer layers.

Here’s a simple schema you can use as a mental model:

[Frameworks & Drivers]

- React/Angular

- Router

- HTTP client

- LocalStorage

- Analytics | v [Interface Adapters]

- Presenters / ViewModels

- Controllers

- API mappers (DTO to/from Domain)

- Gateways | v [Application / Use Cases]

- Interactors

- Orchestration

- Policies

- Transactions (conceptually) | v [Domain / Entities]

- Entities / Value Objects

- Domain services

- Invariants

In frontend terms: the Domain is your most stable code; the UI is your most change-prone code. Your architecture should reflect that.

What is a “boundary” in frontend?

A boundary is any place where you can say:

• “This layer provides a stable interface.”

• “This layer does not import from that layer.”

• “We can test this layer without the other.”

Boundaries are enforced by:

• Folder structure + import rules

• Explicit public API files (index.ts)

• Types and interfaces (ports)

• Dependency injection (composition root)

• Lint rules (e.g., import/no-restricted-paths)

• Code review checklists

The big misconception: “Clean Architecture is only for backend”

Clean Architecture is about dependency direction and business capability ownership. Those exist in frontend too:

• Pricing rules

• Permissions and entitlement logic

• Checkout and payment flows

• Form and validation policies

• State machines for onboarding

• Offline-first sync rules

• Domain-centric calculations (finance, health, logistics)

If these rules live in components, you’re coupling business to UI. Clean Architecture simply gives you a systematic way to reverse that dependency.

Mapping Clean Architecture to React and Angular

To adapt Clean Architecture to frontend, map layers to what you already have.

Domain layer in frontend: “business meaning,” not “backend-like”

The domain layer is:

• Entities and value objects (e.g., Money, Email, CartItem)

• Invariants (rules that must always hold)

• Pure domain functions (no network, no DOM, no time)

• Domain events (optional, but powerful)

It is not:

• API DTO types copied from Swagger

• UI state shape (“isModalOpen”)

• Framework lifecycle logic

A good heuristic: if you can run it in a Node test runner without mocking the world, it likely belongs closer to the domain.

Use cases: the missing middle in many frontends

Use cases (application services, interactors) answer:

• “What does the user want to achieve?”

• “What steps must happen in which order?”

• “Which policies apply?”

• “Which side effects are needed?”

Examples:

• PlaceOrder

• UpdateShippingAddress

• SignInWithOtp

• LoadDashboard

• ToggleFeatureFlag (if product policies demand it)

Use cases are where you coordinate:

• Repositories (network)

• Local persistence (cache)

• Validation policies

• Navigation intents (as outputs, not direct router calls)

• Analytics events (as a port, not a direct SDK call)

Interface adapters: presenters, view models, and mappers

Adapters transform data between worlds:

• API response → domain entities

• Domain entities → UI-friendly view models

• UI events → use case input models

• Errors → user-facing messages

This is where you keep framework friction out of business rules.

Frameworks & drivers: React, Angular, router, data-fetching libs

This layer contains:

• Components, hooks, templates

• Angular modules, providers, interceptors

• Router integration

• Concrete HTTP client (fetch/axios)

• Real analytics SDK, feature-flag SDK

• Browser APIs (storage, history, performance)

The trick is to prevent these imports from leaking inward.

React example mapping

React naturally encourages colocating logic in hooks. Clean Architecture-friendly React flips the default:

• UI components are “thin”: render state, dispatch intents

• A “controller” (often a hook) calls a use case

• The use case depends on ports (interfaces), not concrete fetch

Typical mapping:

• Component → View

• Hook (thin) → Controller / Presenter coordination

• useCase.execute() → Application layer

• Repository interface → Port

• Fetch-based repository → Adapter / Infrastructure

Angular example mapping

Angular’s DI system makes Clean Architecture approachable:

• Use cases can be injectable services (application layer)

• Ports are TypeScript interfaces or injection tokens

• Infrastructure adapters are providers (HTTP, storage)

• Components bind to view models (presenter layer)

Key rule: Angular decorators live at the edges, not in the domain.

How-to: implement Clean Architecture in a TypeScript frontend

This section gives you a concrete, repeatable process you can apply in React or Angular. The goal is not ceremonial layering—it’s controlled dependencies and testable business logic.

Step 1) Identify the core business capability

Pick one vertical slice (a user journey) to avoid boiling the ocean:

• “Add item to cart”

• “Save profile”

• “Search products”

• “Create invoice draft”

Write it as a capability statement:

Capability: “User can add a product to the cart with quantity rules and see accurate totals.”

This is already a domain statement. Great.

Step 2) Model stable domain concepts (entities/value objects)

Keep the domain small and strict. Example:

// Domain: Value Objects and Entities (no framework imports)

type Currency = "USD" | "EUR" | "THB";

class Money {

constructor(public amount: number, public currency: Currency) {

if (!Number.isFinite(amount)) throw new Error("Money amount must be finite");

}

add(other: Money): Money {

if (this.currency !== other.currency) throw new Error("Currency mismatch");

return new Money(this.amount + other.amount, this.currency);

}

multiply(factor: number): Money {

return new Money(this.amount * factor, this.currency);

}

}

class CartItem {

constructor(

public productId: string,

public unitPrice: Money,

public qty: number

) {

if (qty <= 0) throw new Error("Quantity must be positive");

}

subtotal(): Money {

return this.unitPrice.multiply(this.qty);

}

}

Notice what’s missing: no HTTP, no local storage, no React state. This domain is portable and easy to test.

Step 3) Define ports (interfaces) for side effects

Ports are where frontend Clean Architecture becomes practical. Define the minimum you need.

// Ports: describe what the use case needs, not how it's implemented

interface CartRepository {

getCart(): Promise<{ items: CartItem[] }>;

saveCart(items: CartItem[]): Promise<void>;

}

interface ProductCatalog {

getProductPrice(productId: string): Promise<Money>;

}

interface Analytics {

track(eventName: string, props?: Record<string, unknown>): void;

}

These interfaces are your “contracts.” They keep infrastructure details out of your use case.

Step 4) Implement the use case (application layer)

Use cases orchestrate. They should be easy to read and easy to test.

type AddToCartInput = { productId: string; qty: number };

type AddToCartOutput = { items: CartItem[]; total: Money };

class AddToCart {

constructor(

private cartRepo: CartRepository,

private catalog: ProductCatalog,

private analytics: Analytics

) {}

async execute(input: AddToCartInput): Promise<AddToCartOutput> {

const { productId, qty } = input;

// Policy: cap quantity for UX and fraud mitigation

const safeQty = Math.min(Math.max(qty, 1), 20);

const price = await this.catalog.getProductPrice(productId);

const cart = await this.cartRepo.getCart();

// Simple merge policy

const existing = cart.items.find(i => i.productId === productId);

let nextItems: CartItem[];

if (existing) {

const updated = new CartItem(

existing.productId,

existing.unitPrice,

Math.min(existing.qty + safeQty, 20)

);

nextItems = cart.items.map(i => (i.productId === productId ? updated : i));

} else {

nextItems = [...cart.items, new CartItem(productId, price, safeQty)];

}

await this.cartRepo.saveCart(nextItems);

this.analytics.track("cart_add", { productId, qty: safeQty });

const total = nextItems

.map(i => i.subtotal())

.reduce((acc, m) => acc.add(m), new Money(0, price.currency));

return { items: nextItems, total };

}

}

This is “clean” because:

• It depends on abstractions (ports)

• It’s framework-agnostic

• It expresses policy clearly

• It’s straightforward to test with fakes

Step 5) Write fast tests without a DOM

The biggest morale boost is seeing tests become simple.

// Test doubles (in-memory fakes)

class InMemoryCartRepo implements CartRepository {

constructor(private items: CartItem[] = []) {}

async getCart() { return { items: this.items }; }

async saveCart(items: CartItem[]) { this.items = items; }

}

class FakeCatalog implements ProductCatalog {

constructor(private price: Money) {}

async getProductPrice() { return this.price; }

}

class SpyAnalytics implements Analytics {

calls: Array<{ name: string; props?: Record<string, unknown> }> = [];

track(name: string, props?: Record<string, unknown>) { this.calls.push({ name, props }); }

}

Now your test can run in milliseconds.

Step 6) Build infrastructure adapters (HTTP, storage, SDKs)

Adapters implement ports. Keep them boring and replaceable.

// Infrastructure adapter example: REST-based catalog

class HttpProductCatalog implements ProductCatalog {

constructor(private baseUrl: string) {}

async getProductPrice(productId: string): Promise<Money> {

const res = await fetch(`${this.baseUrl}/products/${productId}`);

const json = await res.json(); // { price: number, currency: "USD" }

return new Money(json.price, json.currency);

}

}

// Infrastructure adapter: localStorage cart repo

class LocalStorageCartRepo implements CartRepository {

private key = "cart_v1";

async getCart() {

const raw = localStorage.getItem(this.key);

if (!raw) return { items: [] };

const parsed = JSON.parse(raw);

// Map DTO -> Domain

const items = parsed.items.map((x: any) =>

new CartItem(x.productId, new Money(x.unitPrice.amount, x.unitPrice.currency), x.qty)

);

return { items };

}

async saveCart(items: CartItem[]) {

const dto = {

items: items.map(i => ({

productId: i.productId,

unitPrice: { amount: i.unitPrice.amount, currency: i.unitPrice.currency },

qty: i.qty,

})),

};

localStorage.setItem(this.key, JSON.stringify(dto));

}

}

This mapping layer is where you control drift between API models and domain models. If the backend changes, you adjust the adapter—not your core logic.

Step 7) Connect to UI through a composition root

The composition root is where you instantiate concrete dependencies. This is the "edge" where wiring happens.

// Composition root (React or Angular bootstrap boundary)

const cartRepo = new LocalStorageCartRepo();

const catalog = new HttpProductCatalog("https://api.example.com");

const analytics: Analytics = { track: (n, p) => console.log(n, p) };

const addToCart = new AddToCart(cartRepo, catalog, analytics);

Step 8) Use it from React (thin UI)

In React, keep the component focused on rendering and user intent.

// React-ish pseudo usage

async function onAdd(productId: string) {

const result = await addToCart.execute({ productId, qty: 1 });

// Set state using result.total / result.items

}

Your component doesn’t know about fetch, localStorage, or business rules. It knows: “when user clicks, execute capability.”

Step 9) Use it from Angular (DI-friendly wiring)

In Angular, providers can construct your use case.

// Angular-ish pseudo usage // Provide AddToCart with concrete CartRepository and ProductCatalog // Component injects AddToCart and calls execute()

Again, the component stays thin, while the use case remains stable.

Dependency injection in frontend without pain

“Dependency injection” often sounds like enterprise ceremony. In frontend, keep it pragmatic:

• Use DI only where it improves testability and replaceability

• Keep the DI boundary at the composition root

• Prefer simple factories over global containers unless complexity demands it

The composition root pattern

A clean approach is:

• Inner layers declare interfaces

• Outer layers implement them

• The app root wires them together once

Why it works:

• You can swap implementations (mock, in-memory, real)

• You avoid runtime magic in core logic

• You keep dependencies explicit—great for maintainability

DI techniques that work well in modern frontend

1) Constructor injection (simple, explicit)

Best for use cases and services.

2) Factory functions (great for React)

Create objects once, pass them via props or context.

3) React Context as a dependency boundary

Use Context to provide a small dependency graph.

4) Angular DI (powerful, but keep decorators out of the core)

Angular’s injectors excel at wiring; use them to provide ports and adapters.

5) Lightweight DI libraries (when graphs grow)

Tools like Inversify or tsyringe can help, but they’re optional. Choose them when manual wiring becomes a productivity drain.

A practical rule for teams

If your dependency graph fits on one screen, manual wiring is often best. If it sprawls across dozens of features with multiple implementations (mock/live/offline), a DI container may pay off.

Test strategy: ports make mocking a design choice, not a hack

When your use cases depend on ports:

• Unit tests use fakes (in-memory repos)

• Integration tests use real adapters behind test servers

• E2E tests focus on flows (Cypress/Playwright), not business rules

This layered testing strategy is stable and fast. Leading architects suggest optimizing for “fast feedback loops,” and clean boundaries make that achievable.

Hexagonal, onion, ports and adapters: what differs, what doesn’t

The secondary keyword cluster matters because these patterns are essentially variations of the same idea: protect the core and invert dependencies.

What’s common across all three

• Focus on domain-centric design

• Use interfaces (ports) to decouple from infrastructure

• Implement adapters at the edges

• Encourage testability and replaceability

• Make architecture explicit through boundaries

Where they differ (in practice)

• Hexagonal architecture emphasizes multiple input/output adapters (UI, CLI, tests, API consumers).

• Onion architecture emphasizes concentric layers and strict inward dependencies.

• Ports and adapters is the most implementation-oriented framing: define ports, implement adapters.

Here’s a comparison you can use in architectural discussions:

| Pattern family | Emphasis | Frontend-friendly takeaway |

|---|---|---|

| Hexagonal architecture | Many adapters around a core | Great mental model for UI + tests + offline adapters |

| Onion architecture | Layered dependency flow | Useful for enforcing “no framework in core” rules |

| Ports and adapters | Contracts + implementations | The most actionable for TypeScript and team conventions |

If you can explain your system as “use cases call ports; adapters implement ports,” you’re already applying the essence of these patterns.

Comparing common frontend approaches: MVC, MVP, Atomic Design, DDD

Clean Architecture is not the only game in town. Many teams mix patterns, and that can be healthy—if you understand trade-offs.

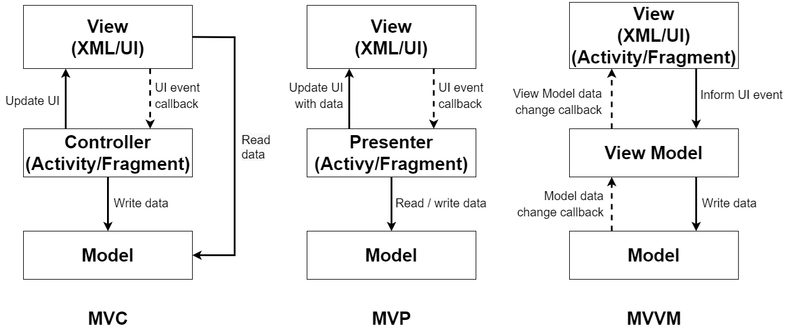

MVC and MVP: good separation, weak dependency control

Classic MVC/MVP can help organize UI logic:

• Controllers/Presenters reduce “fat components”

• Views become simpler

• Testability improves relative to raw component logic

But without explicit ports and dependency rules, MVC/MVP often still allows:

• Direct imports from UI into data access

• Implicit coupling to state libraries

• Cross-feature leakage

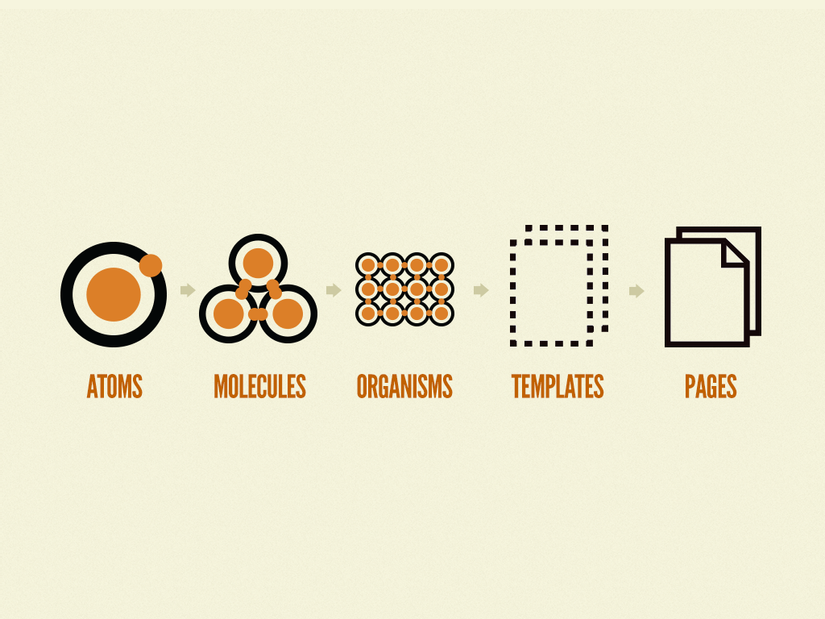

Atomic Design: excellent UI consistency, not a business architecture

Atomic Design is about component taxonomy (atoms, molecules, organisms). It helps:

• Design systems

• Reusable UI libraries

• Visual consistency

It does not, by itself, solve:

• Domain ownership

• Use case orchestration

• Infrastructure isolation

• Team-scale modularity

Atomic Design pairs well with Clean Architecture, but it targets a different problem.

Domain-Driven Design: aligns with Clean Architecture, needs frontend adaptation

DDD is about modeling the domain and managing complexity via:

• Ubiquitous language

• Bounded contexts

• Aggregates and invariants

• Context mapping (including an anti-corruption layer)

DDD concepts translate well to frontend when your UI has significant domain complexity. The main adaptation is: keep domain objects small and focused, and use ports/adapters to integrate with APIs and storage.

A quick comparison for decision-makers

| Approach | Primary strength | Common scaling limitation |

|---|---|---|

| MVC / MVP | Organizes UI logic | Doesn’t enforce infrastructure isolation by default |

| Atomic Design | UI consistency and reuse | Doesn’t structure business logic or dependencies |

| Feature-Sliced Design (FSD) | Team-scale modularity and boundaries | Requires discipline around public APIs and slicing |

This is why many mature frontends converge on a hybrid: Clean Architecture principles for dependency direction + FSD for feature ownership and repository structure.

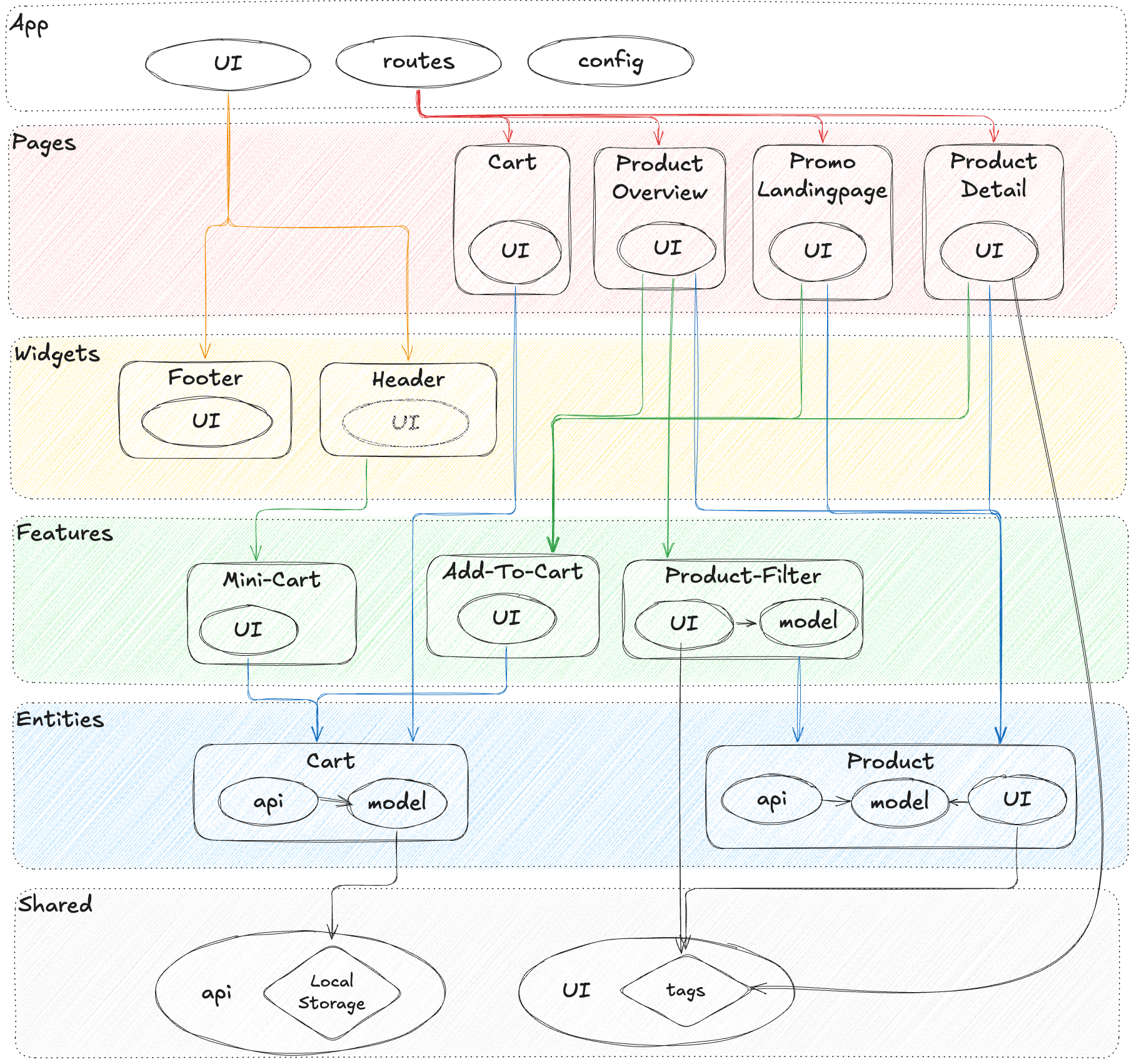

Where Feature-Sliced Design fits

As demonstrated by projects using FSD, the biggest challenge in frontend architecture is not naming layers—it's enforcing boundaries at scale across teams, features, and evolving requirements. This is where Feature-Sliced Design becomes a practical methodology for "Clean Architecture in frontend" without excessive ceremony.

FSD in one sentence

FSD organizes code by business features and domain concepts, with clear layering and public APIs, so that dependencies stay predictable as the codebase grows.

How FSD complements Clean Architecture

Clean Architecture answers: “Which direction should dependencies flow?”

FSD answers: “How do we structure a frontend repository so teams can follow that rule consistently?”

Key shared principles:

• High cohesion within a slice

• Minimal coupling between slices

• Explicit boundaries with public APIs

• Framework code kept at appropriate layers

• Testability through isolation

The FSD layers (pragmatic frontend layering)

A common FSD structure looks like:

src/ app/ # app-wide composition root, providers, routing, init processes/ # cross-page flows (optional) pages/ # route-level pages widgets/ # composite UI blocks (page sections) features/ # user-facing actions (use cases & UI bindings) entities/ # domain entities (models, rules, domain UI) shared/ # shared libs, UI kit, config, api clients

This structure helps you answer daily questions:

• “Where does this code go?”

• “What can import what?”

• “How do we prevent feature-to-feature spaghetti?”

• “Where do use cases live?”

• “What is the public API of a slice?”

A Clean Architecture mapping to FSD

You can map Clean Architecture concepts onto FSD naturally:

• Domain/Entities → entities/ (domain models, invariants, core logic)

• Use cases → features/ (capabilities, orchestration, policies)

• Interface adapters → features/ and shared/ (mappers, gateways, presenters)

• Frameworks & drivers → app/, pages/, shared/ (runtime wiring, router, concrete clients)

This mapping is not dogma—it’s a reliable default that keeps architecture coherent.

Public API as a first-class boundary

A powerful FSD habit is: each slice exposes an explicit entry point:

features/add-to-cart/ index.ts # public API model/ # state + use case wiring ui/ # button, form, view bindings lib/ # helpers

// features/add-to-cart/index.ts // export only what other layers are allowed to consume

With public APIs:

• Imports become intentional (“I depend on this slice”)

• Refactors are safer (internal files can move freely)

• Tooling can enforce boundaries (lint rules)

In real organizations, this reduces architectural entropy more than any diagram.

Migration playbook: from spaghetti UI to clean boundaries

Most teams can’t rewrite. The goal is incremental improvement with continuous delivery.

1) Start with one high-value flow

Choose a flow with:

• Frequent changes

• Many bugs/regressions

• Heavy domain policy

• Multiple integration points (API, storage, analytics)

This ensures quick ROI and visible benefits.

2) Extract a use case behind a UI adapter

Do not reorganize the entire repo first. Extract the capability:

• Create a use case class/function

• Define ports for dependencies

• Implement simple adapters (can wrap existing code)

• Wire via composition root

Even if the first version is imperfect, you’ve created a boundary that can harden over time.

3) Stabilize data mapping with DTO boundaries

A common source of frontend chaos is “DTO drift” (backend payload changes break UI everywhere). Fix it by:

• Mapping DTO → domain at the adapter boundary

• Keeping domain stable and meaningful

• Exposing UI-friendly view models from presenters

This reduces ripple effects dramatically.

4) Enforce import rules gradually

Introduce rules in phases:

• Phase 1: forbid imports from app/ into features/ and entities/

• Phase 2: enforce features/ cannot import other features directly (only via public API, if allowed)

• Phase 3: lock down shared/ to prevent it from becoming a dumping ground

A small, consistent rule set beats a huge rule set nobody remembers.

5) Create “strangler” adapters for legacy modules

If old modules are too coupled:

• Wrap them behind a port

• Use the wrapper in your new use case

• Replace internals later

This is the frontend version of the Strangler Fig pattern.

6) Measure improvement with simple architecture signals

You don’t need perfect metrics. Track a few practical signals:

• Number of cross-feature imports per PR

• Time to add a new developer to a feature

• Ratio of unit tests that run without DOM

• Average files touched per change in a feature

In many teams, these indicators improve quickly once boundaries become habitual.

Is Clean Architecture worth it? A pragmatic decision framework

Clean Architecture adds structure, and structure has a cost. The right question is not “Is it clean?” but “Does it reduce our long-term risk and increase delivery speed?”

It’s usually worth it when…

• The product is long-lived (months → years)

• Team size is growing or multiple squads contribute

• Domain complexity is high (rules, policies, workflows)

• You expect framework churn (major upgrades, library swaps)

• You need reliable testing and fast refactoring

• You integrate with multiple external services (payments, auth, analytics, feature flags)

It may be overkill when…

• The app is small and short-lived

• UI is mostly static content

• Domain logic is minimal

• One developer owns everything end-to-end

• Speed-to-first-demo is the only success metric

A robust methodology for architecture is one that supports evolution. FSD helps teams pick the right level of structure and apply it consistently—without turning every component into an academic exercise.

A practical “complexity budget” checklist

If you answer “yes” to 4+ items, strong boundaries usually pay off:

- Do we have more than one team working in the same frontend?

- Do features frequently affect each other unexpectedly?

- Do we struggle to test business rules without rendering UI?

- Does onboarding take more than a few days to become productive?

- Are refactors risky because logic is scattered across components?

- Do backend/API changes cause widespread breakage?

- Are we planning significant redesigns or platform changes?

When the budget is justified, Clean Architecture principles + FSD structure are an effective combination.

Conclusion

Clean Architecture in frontend is most valuable when it clarifies boundaries: keep domain rules stable, orchestrate behavior through use cases, and isolate frameworks behind ports and adapters. In practice, the biggest win is not a perfect diagram—it’s a codebase where refactoring feels safe, tests are fast, and teams collaborate with confidence. Adopting a structured approach like Feature-Sliced Design (FSD) is a long-term investment in code quality, onboarding speed, and predictable delivery.

Ready to build scalable and maintainable frontend projects? Dive into the official Feature-Sliced Design Documentation to get started.

Have questions or want to share your experience? Visit our homepage to learn more!

Disclaimer: The architectural patterns discussed in this article are based on the Feature-Sliced Design methodology. For detailed implementation guides and the latest updates, please refer to the official documentation.